199A Permanence Dominates Tax Hearing

The House Ways & Means Committee today kicked off the new Congress with a hearing focused on the family and business provisions included in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. But the topic that took center stage is one that’s near and dear to the hearts of millions of Main Street businesses nationwide – addressing the looming expiration of the Section 199A deduction.

The panel first heard testimony from Michelle Gallagher, an S-Corp Advisor and accountant with decades of experience serving individual and family-owned businesses (and who can be seen sporting our “I Love 199A pin!”).

Her opening statement began by calling on lawmakers to not just extend 199A, but to do so swiftly:

The 199A deduction has been critical for businesses organized as [pass-throughs] which represent 99 percent of my business clients, and the vast majority of businesses in Michigan and nationwide. They also employ most of the country’s workers. 199A helped many small business clients stay competitive with large corporations on wages and hiring when inflation was skyrocketing…If the 199A deduction expires, the tax on pass-throughs will go up sharply, while C corps and publicly-traded companies will continue to enjoy their lower, 21-percent permanent rate. This simply is not fair to the Main Street businesses and farmers of our country.

Michelle wasn’t the only person in the room to bring up the importance of extending 199A and the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Throughout the course of the hearing, the issue was raised countless times by lawmakers and witnesses. Here’s Chairman Jason Smith (R-MO):

Small businesses are facing a 43.4 percent tax rate if the 199A small business deduction, as I refer to it, expires. This looming threat impacts decisions they’re making today about whether to invest, grow, hire…If Congress doesn’t act soon, family-owned farms and Main Street businesses will have to start calling estate planners and accountants to figure out how they navigate the potential increases in their tax burdens.

And Rep. Vern Buchannan (R-FL):

As chairman of the Florida Chamber I can tell you we had 130,000 businesses, 90 to 95 percent of them were pass-through entities. And you’re dealing with these potential tax hikes, that’s what scares a lot of people.

And Rep. Jodey Arrington (R-TX):

Everyone benefitted. And those on the lower income spectrum benefitted the most. Actually, the top 1 percent paid more. So we got more progressive in that sense. But all boats rose on the tide of prosperity as the result of good, low, competitive tax rates for our country and for our families.

And Rep. Kevin Hern (R-MO):

Certainty is important. And we’re getting ready to see the largest tax increase in American history starting January 2026 if we don’t do something…199A, it puts parity between small business pass-throughs and C corporations, and 99 percent of businesses in America are pass-throughs. Are there some larger than others? Absolutely. Are we going to be punitive to those who have fought, and grown their businesses as I did, from one person to 1,200 employees? Are we evil because we created jobs?

And Rep. Greg Steube (R-FL):

With many of the TCJA’s provisions expiring, it’s imperative that Congress act this year to ensure we continue to enact pro-growth policies that help American families. In my district the consequences of inaction would be devastating – my constituents on average would experience a 24 percent tax increase if the TCA is allowed to expire.

Finally, here’s Rep. Beth Van Duyne (R-TX) referencing the 199A roundtable we held with her last year:

As part of my work on the Main Street Tax Team we were able to get out of DC and talk to real business owners. We heard about the successes of policies such as Section 199A, which created over $66 billion in savings for Main Street businesses. One of the businesses I met with was Republic National Distributing Company, where I held a roundtable including 25 small businesses including roofers, community banks, and realtors. These are the businesses across the U.S. who are benefitting from this, and this is why Congress must act.

These excerpts are just a small snippet of the support for 199A heard throughout the hearing, and we urge readers to listen to the full recording to get the complete story.

The bottom line is that it’s hard to overstate the importance of making permanent the Section 199A deduction. As the testimony and comments from lawmakers in the hearing made clear, this deduction is a lifeline for millions of Main Street businesses that form the backbone of the American economy. Without it, these job creators face a starkly uneven playing field, with higher tax burdens that could hinder growth, investment, and job creation.

We look forward to working with our allies on Capitol Hill to ensure Section 199A is made a permanent fixture of the Tax Code and thank the members of the Ways & Means Committee for holding this important hearing.

Main Street 199A Resources

In the past, we’ve posted all the studies, data, and other information we’d compiled in support of the 199A deduction (here and here).

With Congress debating the deduction once more – Ways and Means hearing tomorrow! – we thought this would be a good time to repost all this work. It demonstrates both the importance of the pass-through sector to the economy and the importance of Section 199A to the pass-through sector.

The Importance of 199A

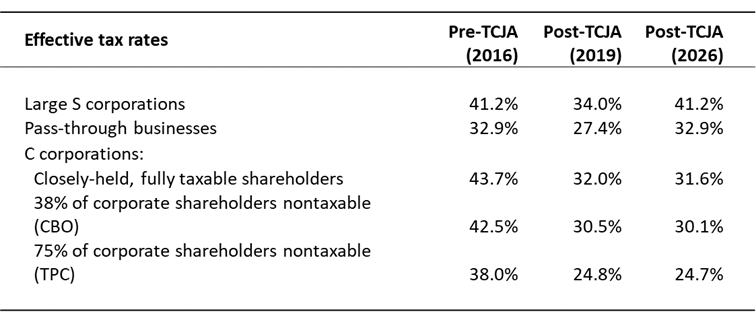

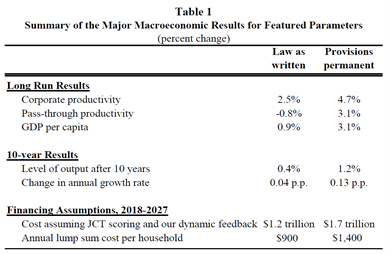

Our recent study by EY’s Robert Carroll demonstrates how the 199A deduction is vital to Main Street parity. The key takeaway is summed up in the table below – the TCJA established rough parity between public corporations and pass-through businesses, but only as long as section 199A is in place. Without 199A, pass-throughs lose out to large, public corporations regardless of what assumptions you make about their size or shareholder makeup:

EY’s numbers aren’t an aberration. Numerous economic studies from the CBO, Treasury, and the private sector all come to a similar conclusion – the effective marginal rates faced by corporations and pass-through businesses post-TCJA are roughly equivalent, but only with section 199A in place. Without section 199A, the comparative rates aren’t even close:

| With 199A Deduction | Without 199A Deduction | |||

| C Corporation | Pass-Through | C Corporation | Pass-Through | |

| DeBacker & Kasher — Market Returns (AEI) | 19.0% | 20.0% | 19.0% | 27.0% |

| DeBacker & Kasher — Above Market Returns (AEI) | 16.0% | 21.0% | 16.0% | 30.0% |

| Barro & Furman (Brookings) | 26.0% | 31.1% | 26.0% | 35.5% |

| Treasury (2021) | 18.9% | 24.2% | 23.2% | 26.4% |

| EY (2023) | 24.8% | 27.4% | 24.7% | 32.9% |

| CBO (2024) | 17.0% | 21.0% | ||

Resources:

- Ken Kies (Op-Ed, Tax Notes): The Ryder Cup and Section 199A – Really!

- EY Study: Relative Tax Treatment of Pass-throughs and C Corporations

- S-Corp: The Importance of 199A

- S-Corp: The Main Street Defense of the 199A Deduction

- S-Corp: Nichols Explains 199A in Tax Notes

- Joint Trades Letter on 199A Permanence

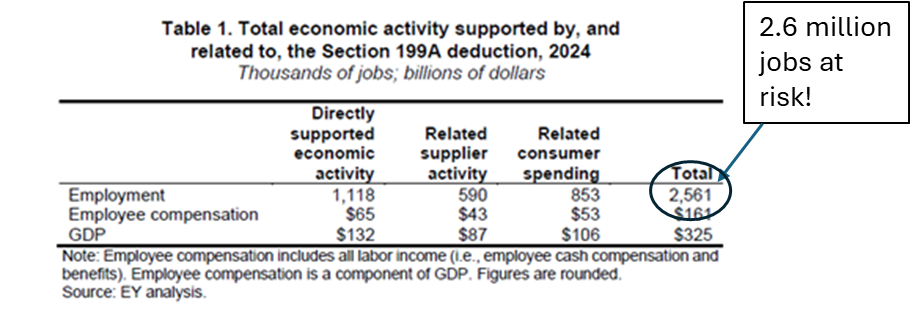

Section 199A Sunset Puts Millions of Jobs at Risk

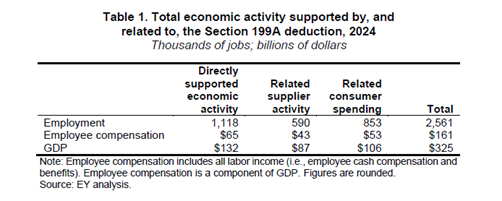

Section 199A supports millions of jobs – jobs that will be put at risk if Congress allows the deduction to sunset. That’s the key take-away from last year’s EY study on the economic footprint of Section 199A.

What did EY find? Section 199A supports 2.6 million jobs, contributes $161 billion to employee compensation, and adds $325 billion to the national economy:

These results highlight the importance of Section 199A and how the expiration of the deduction threatens these jobs. Absent congressional action, 2.6 million jobs will be at risk.

Bottom Line:

- The Section 199A small and family business deduction supports 2.6 million jobs in the United States.

- Allowing 199A to sunset puts all those jobs at risk, resulting in less employment, lower wages, and a smaller economy.

- Congress needs to protect Main Street and the people who work there by adopting the Main Street Certainty Act and make permanent the 199A deduction.

Resources:

- EY Study: Economic activity supported by the Section 199A deduction

- S-Corp: 199A EY Study Briefing Recap & Recording

- Congressman Smucker Press Release

Public Corporations and the Double Tax

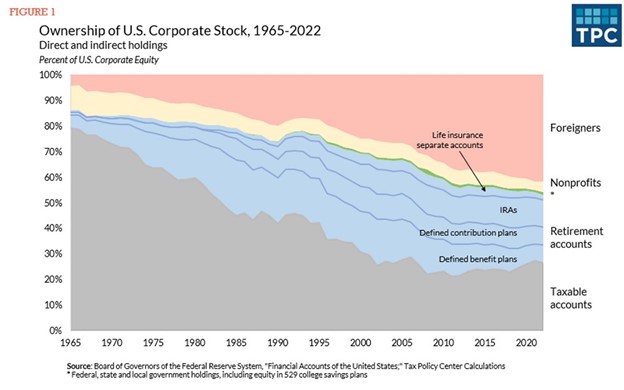

On paper, C corporations face steep tax rates due to the so-called double tax. This theoretical double tax has fooled many observers into believing that public corporations face effective tax rates approaching 40 percent.

The reality, however, is that most corporate shareholders pay little to no tax, largely eliminating the second layer of tax. The Tax Policy Center has the latest data on this front, finding the percentage of taxable shareholders has declined from around four in five back in 1965 to only one in four today:

This means the effective tax rates paid by public corporations are significantly lower than the advertised rates (see the first section for the estimates). They also are far below what comparably-sized pass-throughs face. In an excellent defense of the 199A deduction, former JCT head Ken Kies addressed this issues back in 2021:

…In the United States it’s common to talk about the double tax on corporate earnings. As a general proposition, it’s not fake news: A corporation pays tax on its earnings and the owners of corporations — that is, the shareholders — generally also pay tax on any remaining earnings that are distributed to them.

Based on the best available data, it’s estimated that no more than 9 percent of annual corporate profits are subject to tax a second time, and no more than 14 percent will eventually be taxed upon later distribution (that is, as taxable pension or retirement account distributions). That means that only around a maximum of 23 percent of U.S. corporate earnings ever face a second layer of taxation.

So-called experts who ignore the reality of who owns public corporations today are doing a disservice to the public debate.

Resources:

- Tax Policy Center: Grappling with a Dwindling Shareholder Tax Base

- S-Corp: The “Experts” Get 199A Wrong, Part 2

- S-Corp: S-Corp: C Corps for Everybody?

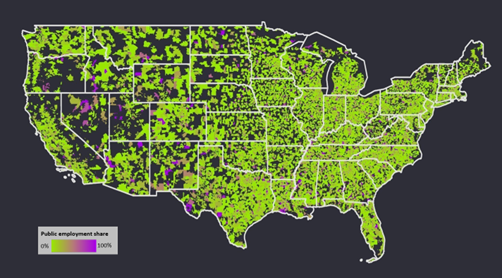

Employment Numbers Confirm Pass-Through Importance

Individually- and family-owned businesses comprise the vast majority of businesses, they employ the majority of private sector workers, and they do so literally everywhere. They are the foundation upon which thousands of communities across this country are constructed.

Analysis shows just how many Americans are employed by individually- and family-owned businesses in each of the country’s 435 Congressional districts. The results are impressive and reveal just how important private businesses are to this nation. Below are a few highlights:

- Pass-through businesses, including S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships, employ 62 percent of the American workforce;

- Private companies (pass-through businesses plus private C corporations) employ 80 percent of workers;

- For every worker employed by a public C corporation (27 million), there are more than four employed by a private business (113 million); and

- Of the 435 total Congressional districts in America, private companies are responsible for 80 percent or more of total employment in 316 of them.

Why does this matter? Because the expiration of the individual and pass-through tax provisions next year would disproportionately harm private businesses, putting those jobs at risk.

The Main Street Tax Certainty Act introduced by Representative Lloyd Smucker and Senator Steve Daines would make 199A a permanent fixture of the code, staving off a massive tax hike and providing these businesses with much needed certainty. It is supported by over 160 national trade associations and is cosponsored by more than 190 Congressmen and more than 30 Senators.

Resources:

- S-Corp: Mobile App

- EY Study: Employment Data by Congressional District

- EY Study: Full Dataset

- Smucker 199A Permanence Bill (H.R. 4721)

- Daines 199A Permanence Bill (S. 1706)

- Joint Trades 199A Support Letter

199A Essential for Economic Growth

Pass-through businesses employ the majority of private sector workers (62 percent) so any increase in their taxes would have broad negative effects on the economy. A Brookings paper authored by Robert Barro and Jason Furman isolates the economic impact of the sunsetting TCJA provisions, including the 199A deduction, the lower individual rates, and expensing:

As you can see, the ‘law as written” column shows pass-through sector productivity under the TCJA is negative. This result is due to the sunsets starting in 2026, plus the TCJA’s base broadening provisions that remain in place. These provisions include the cap on interest deductions, forced amortization of R&E expenses, and the many other business tax base broadening provisions in the TCJA.

The result would be a significant tax hike on pass-through businesses – not relative to tax policy in 2024, but relative to tax policy pre-TCJA. After all the talk of supporting Main Street, going off the fiscal cliff next year means the Trump “tax cuts” would raise taxes on millions of Main Street businesses, just to cut them for Apple and Amazon.

Resources

- Main Street Employers Coalition: Section 199A One-Pager

- Brookings Institute (Robert Barro, Jason Furman): The Macroeconomic Effects of the 2017 Tax Reform

- S-Corp Advisor Lynn Mucenski-Keck: Small Business Committee Testimony

- S-Corp: Pass-Through Businesses & Tax Policy

- S-Corp: More on the Wyden 199A Bill

- S-Corp: A Modest Tax Hike? Not Even Close

- S-Corp: Tax Hike Premise Takes Another Hit

199A Offsets

One objection to Section 199A permanence is it would lose revenue at a time when deficits are large. This concern ignores the fact that the 199A deduction wasn’t adopted in a vacuum. In fact, it was paired with numerous offsetting provisions that raise lots of money – more than 199A costs, actually – and they primarily target upper-income business owners. These provisions include:

- SALT Cap

- Section 461(l) Excess Loss Limitation Rules

- Section 174 R&E Amortization

- Section 199 Manufacturing Deduction Repeal

- Section 163(j) Interest Deduction Cap

- Section 212 Deduction Limitations

As noted above, many of these provisions are permanent and will stay in the tax code even as 199A expires, resulting in a significant tax hike on pass-through businesses. That hike is not relative to the TCJA, but rather the tax code that preceded it.

When Congress addresses the fiscal cliff this year, we fully expect these revenue offsets to be part of the discussion, so for those policymakers worried about adding to the deficit, be assured that we have you covered.

Resources:

- S-Corp: The “Experts” Get 199A Wrong

- S-Corp: A Rate Hike by Any Other Name…Would Still Kill Family Businesses

- S-Corp: White House Shortchanges Main Street

- S-Corp: An Anti-Main Street Budget

- S-Corp: New Budget Continues the Assault on Main Street

Where the Jobs Are

The fight over section 199A has geographical implications too. In a 2021 Wall Street Journal op-ed, S-Corp President Brian Reardon wrote:

A new study from EY demonstrates that private companies supply the vast majority of business-sector jobs nationally—77% of them. Public companies supply only 23%. As important, private-company employment is spread evenly across the country while public-company jobs tend to be concentrated in a few cities and states.

The op-ed references a study showing just how important private companies, including small and family-owned businesses, are to the large swaths of the United States. While public company employment is concentrated on the coasts and city centers, private business employment is spread more evenly across the country, including 22 states where private companies account for more than four out of five workers.

For members of Congress representing those states and districts, pay attention. Getting the balance right between private and public companies is critical to the economic future of your community.

Resources

- Op-Ed, WSJ: The Democratic Plan to Soak Main Street

- S-Corp: Where the Jobs Are

- EY Study: Distribution of Private and Public Company Employment Across the United States

Voter Support

The Gazette featured an op-ed on how Americans really feel about raising taxes on individually- and family-owned businesses and farms:

Contrary to what the White House might tell you, a new poll conducted on behalf of the S Corporation Association confirms that American voters do not support aggressive tax policies or those that target individually- and family-owned businesses and farms.

The results of the survey referenced above were later presented on a webinar by David Winston of the Winston Group, but they speak clearly to the debate before us as well. American voters do not support taxing Main Street.

One reason voters oppose raising taxes on Main Street businesses is they see these tax hikes as inflationary:

Over half the country (52%) believes a tax increase would increase inflation, rather than decrease (11%) or have no impact (19%). Among independents, 55% believe it will increase inflation (7% decrease, 17% no impact).

Keep in mind these findings are from late 2021, well before inflation spiraled out of control.

Resources

- Op-Ed, The Gazette: Biden’s Tax Hikes are Unpopular and Congress Knows It

- S-Corp Webinar: What do Voters Really Think About the Biden Tax Plan?

- Survey Findings

Conclusion

The 2025 fiscal cliff presents an existential crisis for private companies and the workers and communities that rely on them. Absent action, the expiration of the TCJA’s pass-through provisions would accelerate the consolidation of economic power and decision making into the C-suites of a few thousand public companies, leaving thousands of communities worse off.

For anyone still on the fence, we urge you to read the materials outlined above. For those who already understand how critical this fight is, it’s time to engage. Individual and family-owned businesses are the bedrock of local communities nationwide and they work hard to improve the lives of their employees and neighbors every day. That message won’t be heard, however, if family businesses stay on the sideline.

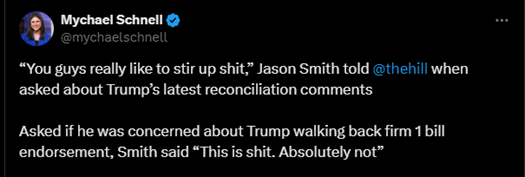

Big Beautiful Bill(s)

Only a couple of days into the new Congress and they’re ready to throw hands!

The Chairman’s frustration is justified. The obsession with process over policy is getting old. As Senator Bob Dole used to say, you should talk about your accomplishments, policies, and facts first. If you don’t have any of those, then fall back on process. “You can always talk about process.” Focusing on process exclusively shifts attention away from the underlying policies and their real-world consequences for Main Street and elsewhere.

It’s also a waste of time. At the end of the day, the reconciliation bill(s) will include whatever magic mixture of policies gets to a majority. If that’s one big omnibus, great. If it’s several smaller bills, that’s fine too. Donald Trump appears to understand this. With just a 2-vote margin in the House, it’s also reasonable to expect the path to finding that magic mixture will be messy, so buckle up.

For Main Street, the key is to ignore all the process talk and keep focused on the goal – building maximum support for 199A permanence so when Congress does take up the tax bill, we’re ready.

Tax Hearing & Timing

Speaking of buckling up, the Ways and Means Committee is hitting the ground running. It will hold a hearing on the expiring tax provisions next Tuesday, January 14th. Word is at least two of the witnesses will focus on 199A and its importance to the economy and jobs. Have we mentioned 63 percent of workers are employed by pass-through businesses? (Download the S-Corp Jobs App here!)

In terms of overall timing, House leadership has been signaling for months they wanted to move quickly to address the fiscal cliff. Just this week, Speaker Johnson said he wants to adopt a budget in March to tee up House consideration of a reconciliation bill in April. Worst case scenario, he said, is a bill on the President’s desk before Memorial Day. Is that possible?

Yes, it is. President Bush announced his Jobs and Growth tax package on January 7, 2003 and signed it into law on May 28th. Majorities were tight back then too, with both the budget and resulting reconciliation bill getting the bare minimum 50 votes in the Senate, with the Vice President breaking the ties.

The difference this time around is the nature of the challenge. The 2003 bill was an effort to boost the economy by accelerating the tax benefits of the 2001 tax bill. Today’s challenge is more serious — how to avoid a massive tax hike on Main Street businesses that puts millions of jobs at risk.

The fact that we’re talking about this challenge Day 1 is helpful and a strong signal that the Congress is serious about avoiding those tax hikes. Much more to come.

CTA Update | January 7, 2025

Notable Developments

- Government appeals to SCOTUS

- Lawmakers still pushing for CTA repeal

- Yet another Treasury hack

* * *

Legal Update

Immediately following the reinstatement of the nationwide injunction against the CTA by the Fifth Circuit, the government asked the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn that ruling and restore the filing deadline while the broader case remains pending. As SCOTUS Blog notes, the government’s argument focuses in part on whether federal courts have the authority to issue nationwide injunctions in the first place:

More broadly, [Solicitor General] Prelogar suggested that the justices could weigh in on the propriety of so-called “universal injunctions” – orders barring the government from enforcing the law anywhere in the country. Some of the court’s conservative justices – Clarence Thomas, Neil Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh – have indicated in the past that the Supreme Court should address whether such injunctions are proper.

We’ll be keeping a close eye on those developments but as we noted previously, absent SCOTUS intervention, the nationwide injunction will remain in place at least through March 25th when the Fifth Circuit will hear oral arguments.

* * *

Hill Update

Last week Representatives Harriet Hageman (R-WY) and Warren Davidson (R-OH) penned an excellent op-ed in the Wall Street Journal that calls on lawmakers to repeal the CTA altogether in the new Congress:

Republicans have introduced H.R. 8147, the Repealing Big Brother Overreach Act, which would take this unconstitutional law off the books and protect the privacy and freedom of small businesses and their owners.

The court that issued the injunction against the Corporate Transparency Act called it a “quasi-Orwellian” law that would “rubber-stamp a new form of federal power” with unprecedented mandates, undermine the U.S. system of federalism and set a dangerous precedent. A panel of the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of appeals stayed the injunction, another panel reinstated it, and the appellate court will hear oral arguments in March.

Congress shouldn’t wait for the courts to rescue it from its own bad ideas. Our policies should unleash the entrepreneurs who fuel innovation, create jobs and keep the American dream alive. We shouldn’t shackle them, regulate them to death and doom them to failure.

Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) also closed out 2024 with a plug for his repeal legislation on X.com:

With the 2024 filing deadline now behind us, it’s encouraging to see lawmakers keeping up the pressure and ensuring the CTA remains front and center. We look forward to seeing both repeal bills reintroduced in the new Congress and working with these Members to getting them enacted.

* * *

Treasury Database Hacked

One of the less-discussed shortcomings of the CTA is that it mandates the collection of tens of millions of pieces of sensitive personal information, and warehouses it all an agency with a spotty record of keeping that data secure. Last week we got a timely reminder of those vulnerabilities, as reported by the Washington Post:

Chinese government hackers breached a highly sensitive office in the Treasury Department that administers economic sanctions against countries and groups of individuals — one of the most potent tools possessed by the United States to achieve national security aims, according to U.S. officials.

…Even unclassified documents can be very useful to a competitor like China, current and former officials said. A breach of OFAC, in particular, could lead to the disclosure of sensitive information about government sanctions deliberations. Before designating a target, OFAC compiles an “administrative record” that purports to show how the evidence collected meets the statutory or regulatory criteria for designation.

The records can include everything from open-source materials to “law enforcement sensitive” information and classified material provided by U.S. or foreign law enforcement, according to four former government officials.

When it comes to securing information collected under the CTA, FinCEN’s stance has essentially been “this time will be different.” Given the relative frequency of these breaches, that’s hard to believe.

CTA Injunction Reinstated!

The Corporate Transparency Act saga took a welcome turn yesterday after a Fifth Circuit Court panel reinstated the nationwide injunction against the statute.

As a result of the order, Main Street businesses are not required to comply with the Corporate Transparency Act’s reporting requirements until the Fifth Circuit is able to more fully consider the injunction and the underlying merits of the legal challenge. The key paragraphs from that ruling are below:

On December 3, 2024, the district court entered an order enjoining enforcement of the Corporate Transparency Act and its corresponding Reporting Rule. The Government requested a stay of the preliminary injunction, which the district court denied. The Government appealed, and on December 23, 2024, a motions panel of this court granted the government’s emergency motion for a stay pending appeal. The order also expedited the appeal to the next available oral argument panel.

The merits panel now has the appeal, which remains expedited, and a briefing schedule will issue forthwith. However, in order to preserve the constitutional status quo while the merits panel considers the parties’ weighty substantive arguments, that part of the motions-panel order granting the Government’s motion to stay the district court’s preliminary injunction enjoining enforcement of the CTA and the Reporting Rule is VACATED.

The panel also announced today that it would hear arguments on March 25 on whether to keep the injunction in place while the broader case is heard by the full court. So absent the federal government appealing yesterday’s decision to the Supreme Court – and SCOTUS intervening in the case – the injunction will stay in place through at least the end of March 2025, at the earliest. In other words, yesterday’s order means covered entities do not need to file their Beneficial Ownership Information reports prior to that proceeding.

Meanwhile, we are still waiting on the Eleventh Circuit ruling on the case from Alabama and expecting a decision soon from the Western District of Michigan where the judge has already signaled his sympathy for the plaintiffs.

And finally, the new administration takes office on January 20th and S-Corp is working to get an administrative delay implemented through the end of 2025. Key members of the Trump team have already weighed in against the CTA (here, here and here). We just need to turn those concerns into action.

The unpredictability we’re seeing in the courts is a central part of our argument for an administrative delay. Yesterday’s ruling is a welcome development that should give us the time necessary to get that done.