S-Corp’s mantra for tax reform is “S corps for everybody!” Tax all businesses once, tax them when the money is earned, tax them at a reasonable rate, and then leave them alone. In other words, tax them like S corporations. Moving the Tax Code towards what we call a “single tax system” would level the playing field for all types of businesses while eliminating the complexity and distortions created by the double corporate tax.

This approach contrasts completely with the vision outlined in last week’s paper by Kyle Pomerleau and Don Schnieder (P-S). There are lots of moving parts here, but the short version is they would use next year’s fiscal cliff as an excuse to cut taxes for public C corporations while raising them on Main Street businesses. If you’ve been wondering how the corporate sector was going to respond to next year’s looming tax hikes on pass-throughs and individuals, look no further.

Tax Cuts for Me, Tax Hikes for Thee

Public corporations have three advantages over private companies regardless of how those private companies are organized:

- They have access to cheaper capital through the public equity and debt markets;

- Their shareholders often pay little or no shareholder level taxes; and

- They aren’t affected by the estate tax.

By contrast, access to capital is a huge challenge for private companies. With few exceptions their shareholders are always individuals or trusts who are fully taxable, and every private company of any size spends a considerable amount of time and resources trying to manage around the estate tax.

This is a tax discussion so we’ll set aside the first point for now, but challenges two and three are products of a poorly designed tax code. Any tax reform plan worth considering would seek to address those issues.

To their credit, P-S would eliminate the estate tax. That helps, particularly in the context of businesses hoping to continue a legacy of family ownership. They then step all over that decision by either (Option 1) raising taxes on pass-through businesses while lowering them for C corporations or (Option 2) forcing all larger private companies into the double corporate tax.

What would the corporate rate be under their plan? 21 percent. What is the double tax under their plan? 23.8 percent. They start by assuming the TCJA’s corporate relief remains in place and then proceed to offer America’s largest public companies even more benefits by extending full expensing, curbing the impact of the interest deduction cap, eliminating the corporate AMT, and other changes.

Pass-through businesses don’t fare quite as well. P-S would either repeal the 199A deduction outright – they mention this several times lest it escape our notice – or replace it with a “return on capital formula” that’s so narrow and laughably complex as to be beneath discussion.

They also would raise taxes on pass-throughs by allowing the current top rates to revert to their pre-TCJA levels while reducing their income thresholds to new, lower levels. The result would subject pass-through businesses to higher rates imposed on a broader base of income. Just to be clear, those are higher rates and a broader base compared to their pre-TCJA levels, not current law.

This treatment is apparently justified by their observation that pass-throughs are making out like bandits under the TCJA:

Although lawmakers were correct to be concerned about how differences in the taxation of pass-through businesses and C corporations affect behavior, Section 199A reduced the statutory tax rate on business income far below the tax rate on labor compensation, increasing the incentive to reclassify income from labor compensation to capital income. It also increased the competitive advantage of pass-through businesses over traditional C corporations, discouraging companies from incorporating.

So many mistakes in one paragraph. Section 199A doesn’t discourage “incorporation” (S corps are corporations too); 199A reduced the effective rate, not the statutory rate (it’s a deduction); and P-S offer no evidence for their reclassification claim because it doesn’t exist. We are aware of no post-TCJA study finding unusual levels of workers shifting to independent contractor status.

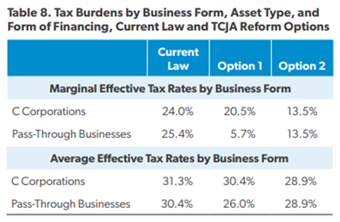

More to the point, “worker versus pass-through” is not the critical comparison here. S corps don’t compete with workers, they hire them. S corps compete with public C corps, and here is where P-S’s own calculations belie the notion that pass-throughs have a rate advantage. Here’s the key portions of Table 8:

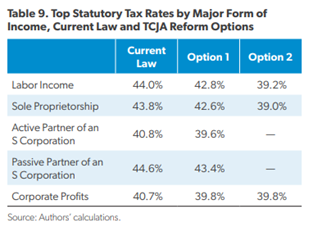

And here’s Table 9:

Neither table reveals a demonstrative advantage for pass-throughs. If anything, they reveal rough rate parity. Moreover, the tables skip over several important details, such as the fact that the pass-through tax burden includes smaller companies paying the lower rates, whereas the corporate tax is imposed on large public companies almost exclusively. They also ignore that the 39.8 percent rate for corporations only applies to private companies whose shareholders are fully taxable, as most public company shareholders don’t pay the full tax so their actual effective rate is much lower than what’s reported here.

Tax Policy Center on Shareholders, Again

That last point is very, very important. One of the head scratching aspects of P-S is their total neglect of the damage the double corporate tax does to the economy. They simply don’t mention it, let alone reflect on its implications. Preserving the current corporate treatment, regardless of how distortionary, was apparently their starting point.

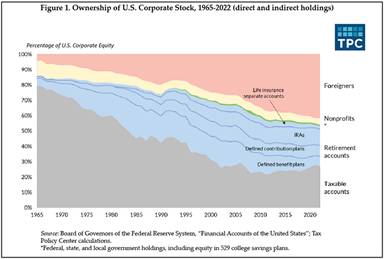

And distortionary it is. Just this week, the Tax Policy Center released a more fulsome version of its 2016 analysis of how the profile of corporate shareholders corporations has shifted in recent decades. The profile has migrated from mostly taxable individuals to being dominated by tax exempt foreign investors, retirement accounts, and other tax-exempt entities.

If you separate the business community into public and private companies, then the blue, yellow and pink shareholders are almost universally reserved for public companies. You don’t get a lot of sovereign wealth funds investing in smaller, private companies.

So while the percentage of taxable shareholders of public companies has dropped, the profile of private company shareholders has remained the same – fully taxable. As authors Rosenthal and Mucciolo write:

First publicly reported in 2016, the pronounced shift from taxable to tax-exempt shareholders complicates tax policy. Policymakers who seek to increase shareholder taxes, for instance, must grapple with a relatively small group of taxable accounts. Policymakers pursuing corporate tax cuts could send a large share of the benefit to foreign investors, at least in the short run. And policymakers seeking to stem corporate stock buybacks must address the tax advantages of buybacks over dividends to foreign shareholders — and to a lesser extent to domestic shareholders.

P-S would preserve this disparity as is, with public corporate shareholders paying little to no second layer of tax while the shareholders of private companies pay the full boat. They then compound this inequity by arguing that all larger pass-through businesses should be forced into the corporate double tax.

What’s interesting is that P-S acknowledge the importance of reducing distortions generated by the Tax Code, and then promptly ignore the role the double corporate tax plays here. They observe:

Timing of Realization. The current tax system relies, in part, on a “realization” principle. For administrative convenience, taxpayers are often taxed only when they realize income. For example, capital gains and losses are counted only when a taxpayer disposes of an asset. As a result, taxpayers have an incentive to hold off on selling appreciated assets and accelerate the sale of an asset to realize a loss. Ideally, taxation would not distort transactions like this.

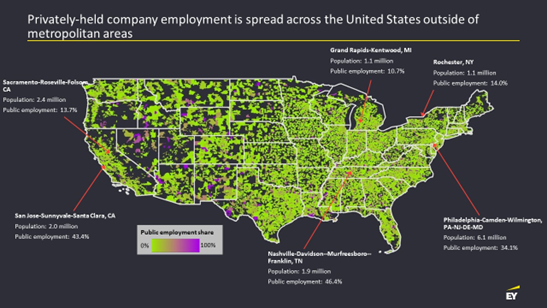

This failure has geographic implications. As our work with EY has shown, public company employment tends to be concentrated in city centers and the coasts, whereas private company employment, including pass-throughs, is spread more evenly across the country. By further distorting the Tax Code in favor of public companies, P-S would harm large parts of the country.

The irony is that this is why S corporations were created in the first place. Congress back in 1958 recognized that closely-held businesses were disadvantaged under the double corporate tax and made the single tax system more widely available in response. Today’s rates are different but the essential challenge is the same.

Pass-Through Tax Hikes

Finally, let’s revisit the justifications P-S identify for why Section 199A was created in the first place. Parity and economic growth were definitely in the mix, but the primary reason the Main Street community argued for rate relief was our desire to avoid a tax hike.

Starting with the Obama budget and extending through all those Camp drafts, Paul Ryan’s efforts when he chaired Ways and Means, and finally the Brady draft, Main Street correctly argued that the base broadening included in the corporate reforms would result in a tax hike on the pass-through sector. It’s our tax base too, after all. TCJA base broadeners that raise taxes on pass-throughs included:

- SALT Cap

- Section 163(j) Interest Deduction Cap

- Section 461(l) Loss Limitation Rules

- Section 212 Deduction Limitations

- Section 199 Manufacturing Deduction Repeal

- Section 174 R&E Amortization

Those tax hikes are preserved in the P-S plan without the Section 199A deduction to help offset them. The P-S plan would make the pass-through tax base broader and their rates higher than pre-TCJA.

Full Circle

We are in danger of coming full circle here. Pre-1986 tax reform, the C corporation was the tax shelter of choice; every rich person had one. They would earn their income in the C corporation and then load up the company with as many personal expenses as possible – apartments, cars, trips, whatever they could get away with. The goal was to apply the lower corporate rate to a smaller base of income.

This gaming ended post-86 when rates on individuals, pass-throughs and C corporations were consolidated into the same neighborhood (for a while, the top rates were even the same). The result was the abandonment of the C corporation shelter and a massive shift of business activity into the superior pass-through form.

Now P-S and their colleagues would return us to the bad old days of tax cheating C corporations. It’s not an improvement, and it’s going to hurt most of the country. Congress should reject this approach.