When Congress finishes work on the tax package pending in the Senate, we expect the conversation to pivot rapidly to what we should do about all those expiring TCJA provisions at the end of 2025.

For S-Corp and its allies, our priority is to make the Section 199A deduction permanent and a big hurdle there is the lack of understanding of how pass-throughs are taxed and why the Section 199A small business deduction is critical to their success.

For example, of all the Republicans who served on Ways and Means during the TCJA debate, only five remain today. The staff turnover is even more dramatic. So educating members and staff through briefings, panels, op-eds and good old-fashioned shoe leather lobbying is very much in the plan for the coming months.

What we might have overlooked, but what is obviously critical and necessary, is the need to educate the so-called experts too — people like Reuven S. Avi-Yonah who writes for Tax Notes and is a professor at the U of M Law School. Reading his articles from the past week, it’s clear he has no idea how 199A works or why it’s necessary.

Here’s what he wrote in his most recent piece and why it’s wrong and completely missing the point about 199A.

Avi-Yonah: The passthrough provisions are totally unnecessary. As noted, the TCJA was driven by two key considerations: the desire for a low corporate tax rate, and the determination not to significantly reduce the top marginal rate on ordinary income.

Response: This characterization is simply wrong. The TCJA was certainly driven by the desire to cut the corporate rate, but Congress also wanted to cut individual rates (and they did – the House bill reduced the top individual rate to 35 percent). The challenge was the individual rate cuts were hugely expensive, and they didn’t have room for large cuts to both the individual and corporate rates. Section 199A was born as a bridge between the two competing rates to protect pass-through employers.

Avi-Yonah: Because owners of passthroughs pay tax at the ordinary income rate, this created the perception that the bill is unfair to passthrough owners.

But this perception is wrong for three reasons.

First, many passthrough owners (for example, hedge fund managers and investors) pay tax at a 23.8 percent rate on capital gains and dividends, not the ordinary income rate.

Response: Ah, here it is – the old “hedge funds and law firms” slander. There are 5 million S corporations, 4 million partnerships, 4 million LLCs, and about 20 million sole proprietors in this country. That’s 33 million businesses all being taxed under the pass-through model. Meanwhile, there are only about 4,000 hedge funds, and some of those are organized as C corps. So “many” pass-through business owners get carried interest treatment? Hardly.

Worse, hedge funds are considered “Specified Services Trade or Businesses” under 199A and therefore ineligible for the deduction.

Item #1 in Reuven’s case for eliminating Section 199A is a sector making up less than 0.012 percent of all pass-throughs, a sector that doesn’t even get the deduction. Brilliant.

Avi-Yonah: Second, taxable individual shareholders in C corporations are subject to a second level of tax on distributions and capital gains at 23.8 percent, so the after-tax return under the TCJA’s rate structure is (100 – 21 = 79 – (23.8 * 0.79) = 60.2), which is almost identical to the after-tax return on a passthrough investment, even if there was no rate reduction for passthrough income (100 – 37 = 63).

Response: We are well aware of the second layer of tax and have included it in all our calculations of what constitutes parity. We’ve written about it extensively here, here, and here. The nuance Avi-Yonah misses is that, these days, almost all C corporation income is earned by public companies where three out of four of their shareholders pay either zero taxes or greatly deferred (and therefore lower) taxes. As the Tax Policy Center writes:

More than 75 percent of corporate shareholders, however, are exempt from U.S. shareholder-level taxes because they are either tax exempt organizations like university endowments or retirement and pension funds, or are foreign shareholders, who generally are not liable for those taxes.8 For those shareholders, the only tax they face is the corporate-level tax.

So for the Harvard endowment, there is no second layer of tax. For a pension plan, the deferred nature of the tax means its effective rate is well below the statutory rate. This tax advantage gives the C corporations they invest in a huge advantage when it comes to their effective tax rates and cost of capital.

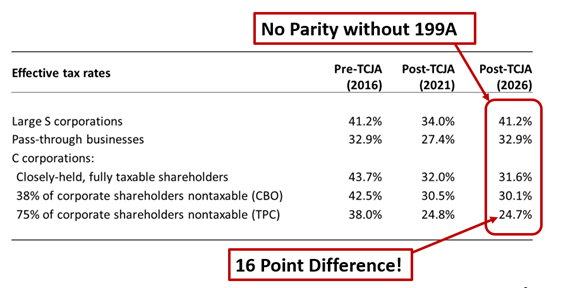

Understanding this nuance, we have spent years and lots of resources estimating exactly where parity lies. This table from EY takes into account all those factors, and estimates that the TCJA came close to rough justice for large private companies when compared to their public competitors, but only with 199A in place.

Avi-Yonah: Third, if owners of passthroughs do not like the 37 percent tax on passthrough income, they need only check the box and their passthrough magically becomes a C corporation taxed at 21 percent. If you hate the rate, incorporate.

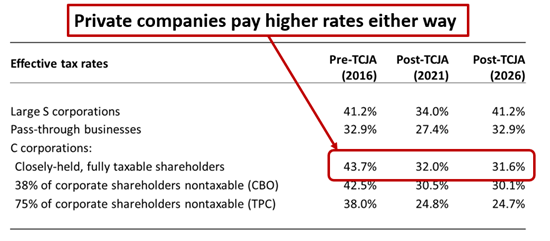

Response: We love it when tax professors rhythm. We love it more when they do their homework. The same EY study showing general parity under 199A also shows why private companies, particularly S corporations, have a hard time competing with public companies under the corporate tax structure. While most public company shareholders are tax advantaged, all S corporation shareholders are, by definition, fully taxable individuals.

That means the double tax public companies largely avoid applies fully to converted private companies. We don’t have a clever rhythm, but it’s clear private companies get screwed whether they are an S or C corporation.

Add on top of that the fact that public companies don’t have to worry about the estate tax and have full access to the public equity and credit markets, and you can see why there’s been so much economic consolidation taking place in recent years. Public companies already have a lower cost of capital advantage – we don’t need the tax code making it worse.

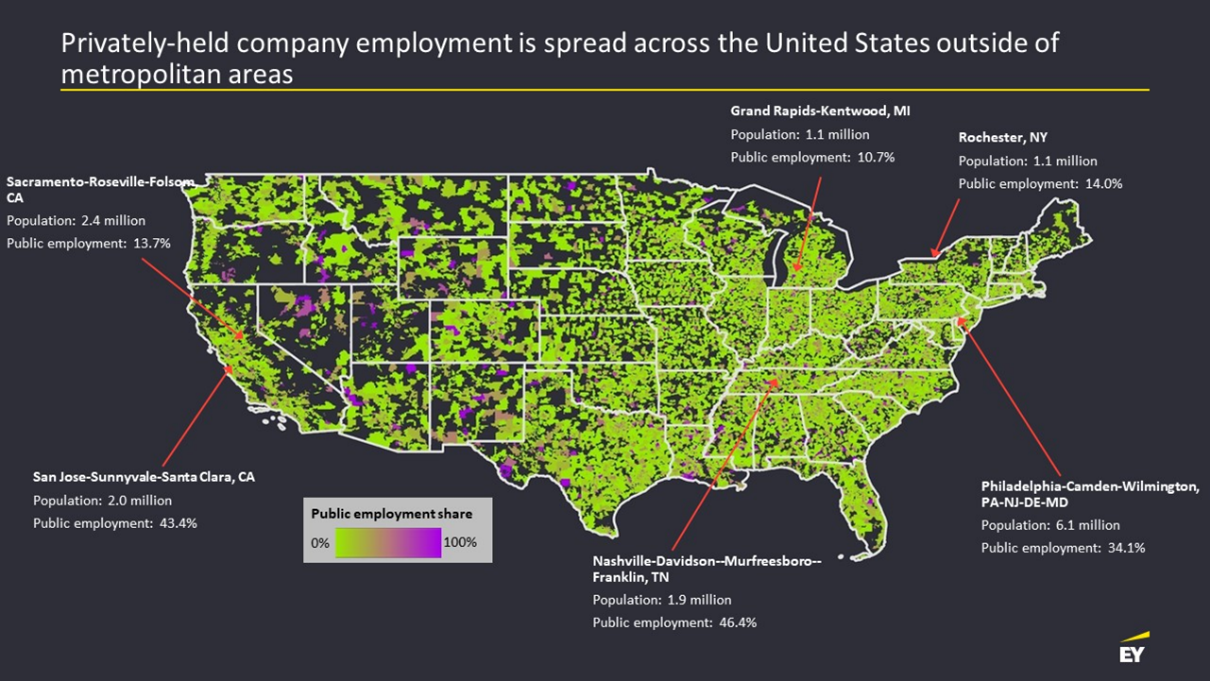

This disparity has significant regional implications. A heatmap from our friends at EY shows the difference in public and private company employment. Public company employment is concentrated in the city centers and coast, while private company employment is spread more evenly across the country.

The education challenge confronting S-Corp in the coming tax fight is daunting. We need to arm all our friends and allies with good, accurate information as to why the 199A small business deduction is so important. We also need to address all the misinformation being spread by the so-called experts. This is a serious debate where the economic future of communities across the country is at stake. It deserves more than casual, poorly considered commentary.