199A on the Line as House Prepares to Vote

With the House preparing to vote as early as today on the Senate-passed reconciliation bill, any lawmakers still undecided should take a close look at what’s at stake for Main Street businesses across the country. Absent congressional action, these businesses will be hit with an unprecedented tax hike, putting millions of jobs and billions in wages and economic growth at risk.

The urgency here stems from the looming expiration of the Section 199A deduction, which sunsets at the end of this year. We’ve done a number of studies in the past showing the benefits of 199A when it comes to achieving rough parity between pass-throughs and publicly-traded corporations. To build on that data we asked EY last year to estimate how much economic activity is supported by the provision, and the numbers are staggering.

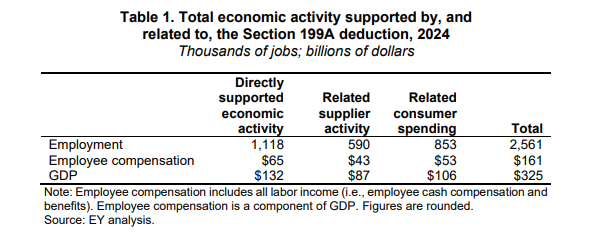

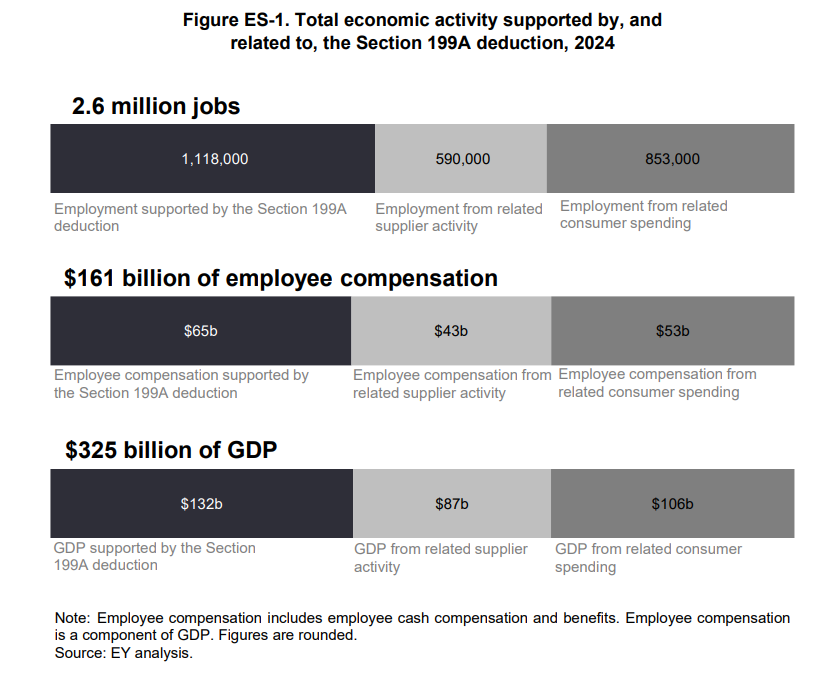

According to EY, Section 199A supports 2.6 million jobs, contributes $161 billion to employee compensation, and adds $325 billion to the national economy:

Drilling down on the jobs figures, the study found that 199A supports 1.1 million jobs directly, 590 thousand jobs through increased employee compensation, and another 853 thousand jobs from related consumer spending increases:

That’s why, as Chairman Jason Smith has said repeatedly, “failure is not an option.” Main Street businesses are the backbone of the American economy and supply well over half of all private sector jobs. They rely on Section 199A to hire, reinvest in their communities, and thrive.

As policymakers cast their votes, they should be clear-eyed about the consequences of inaction. Letting Section 199A expire would not just raise taxes — it would undermine millions of jobs, depress wages, and tilt the playing field further in favor of large, publicly traded corporations. It’s up to the House to finish the job and deliver the certainty Main Street needs to keep driving the American economy forward.

Main Street Supports Senate Tax Bill

A strong coalition of Main Street trades came out today in strong support of the Big Beautiful Bill pending before the Senate. A coalition letter signed by more than 90 trade associations reads:

This legislation builds on the foundation laid by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and advances a forward-looking, pro-growth tax agenda that supports tens of millions of Main Street enterprises. Critically, it would provide long-overdue certainty to the more than 95 percent of American businesses organized as S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships — businesses that employ a large majority of the private sector workforce and serve as the economic engine of communities nationwide.

Among the most significant provisions for these businesses are the permanent extension of the Section 199A deduction and the retention of the 37-percent top individual rate. These measures reflect the need for a competitive and equitable tax structure that recognizes the importance of rate parity between pass-through businesses and C corporations, and helps ensure that these employers can continue to invest, hire, and grow.

Section 199A permanence has been our top priority for several years, and it’s encouraging to see lawmakers respond with a serious effort to protect Main Street from a looming tax hike. Similarly, while past drafts called for new limitations on SALT deductibility for pass-throughs, the Senate bill goes a different direction:

We also applaud lawmakers for their commitment to ensuring parity when it comes to the deductibility of state and local taxes (SALT) incurred by pass-through businesses. This recently-released draft rightly preserves their longstanding ability to deduct SALT expenses as an ordinary and necessary cost of doing business. This policy reflects a clear understanding that pass-through businesses should not be treated less favorably than their C corporation counterparts and reinforces the principle of equal treatment under the tax code.

Among the other important changes included in the bill is a return to the current Section 461(l) excess loss language, which lawmakers had sought to expand.

There’s a lot to like about this current Senate package. With key wins on 199A permanence, SALT deductibility, excess loss limitations, and other critical provisions, the bill marks a major step toward a more stable and competitive tax environment for pass-through businesses. We look forward to seeing this bill advanced and ultimately being signed into law in the coming days.

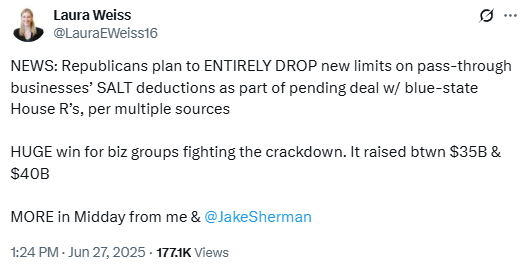

Big Main Street Win on SALT

Here’s a good news story to kick off the weekend – Punchbowl News reports that lawmakers are striking the onerous SALT limitation from the reconciliation package as part of a broader compromise between the House and Senate:

The outlet also reports that the White House played a key role in helping broker the deal:

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is briefing Senate Republicans behind closed doors at their lunch now about a SALT deal he clinched with the White House and blue-state House Republicans…Speaker Mike Johnson and James Braid, the White House’s legislative affairs liaison, are in the Senate GOP lunch.

Under the arrangement, the SALT cap for individuals would be set at $40,000 with a five-year sunset, along with income limitations. But for Main Street businesses, the far more important piece here is the removal of language that would have prevented pass-throughs from deducting their full SALT, potentially invalidating our longstanding SALT Parity efforts at the expense of millions of companies.

So a huge win for Main Street – particularly when coupled with the permanent extension of Section 199A – but the deal isn’t final yet. It still needs approval from Senate Republicans, none of whom hail from blue states and have therefore been leery of a more generous SALT cap for individuals. That said, Punchbowl News spoke to several GOP aides that expressed confidence Bessent and others could get Senate Republicans on board, so fingers crossed for a positive outcome.

There are still a number of other policy issues to work out, but with momentum clearly on Republicans’ side and President Trump doubling down today on the July 4 timeline for passage, there’s a decent chance the One Big Beautiful Bill gets enacted into law before the end of next week. In the meantime, S-Corp and its allies will be working the phones to express our strong support for the revised tax title and help to get it across the finish line.

Main Street Backs 199A Expansion

With the reconciliation bill process reaching its final stages,120 trade associations today called on the Senate to incorporate a key part of the House-passed bill: an expansion of the 199A deduction from 20 to 23 percent. As the letter states:

Expanding Section 199A will help preserve tax parity between pass-through businesses and larger public corporations while helping ensure the Senate bill does not raise taxes on millions of Main Street businesses.

The Section 199A deduction plays a vital role in preserving competitive neutrality in the Tax Code. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reduced the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. In doing so, it left pass-through businesses – which pay taxes at much higher individual rates – at risk of a long-term competitive disadvantage. Section 199A was adopted to mitigate this imbalance and preserve a level playing field.

Why is an enhanced deduction necessary? Beyond being good policy, it also helps mitigate some of the tax hikes included in the Senate bill:

The Senate bill would make permanent the 199A deduction but also would cut in half their ability to deduct State and Local Taxes (SALT) as a business expense. The net result will be a tax hike on millions of pass-through businesses relative to what they currently pay.

Expanding 199A deduction would offset this tax hike. It builds on a policy with a proven track record. Since its enactment, Section 199A has helped tens of millions of Main Street businesses reinvest in their operations and workforce. Data from the IRS and Treasury confirm that the deduction’s benefits flow to job creators in every community and every congressional district in the country. The deduction represents a critical tool for weathering economic headwinds and remaining competitive in an increasingly consolidated marketplace.

The House-passed expansion to 23 percent is modest but meaningful. It ensures that the Tax Code reflects the economic reality pass-through businesses face and recognizes their role as America’s leading source of private-sector employment.

With the reconciliation bill nearing the finish line, the Senate has a real opportunity to deliver certainty, fairness, and economic strength to the backbone of the U.S. economy. Lawmakers should seize it by adopting the House’s 199A expansion and ensure that Main Street doesn’t shoulder a tax hike in the final package.

WSJ is Wrong on SALT Parity

To whoever signed off on yesterday’s Wall Street Journal editorial attacking the ability of Main Street businesses to deduct their SALT payments – just like C corporations do – S-Corp has a bridge to sell you. Seriously, you got played.

The piece starts off wrong and gets worse from there. Here’s what it says:

Senate Republicans appear to be acquiescing to demands by House Republicans from high-tax states to raise the $10,000 limit on the state-and-local tax deduction to $40,000. In return for this gift to spendthrift progressive states, they should at least close a giant loophole in the cap.

The $10,000 cap on the state-and-local tax deduction was one of the 2017 GOP tax reform’s main achievements. But the dirty little secret is that many wealthy denizens of high-tax states aren’t affected since three dozen states have created a loophole for owners of and partners in pass-through business entities.

So the 36 states that have enacted our SALT Parity bills – including Alabama, Georgia, Louisianna, Oklahoma, Utah, Montana, Idaho, North Carolina, Nebraska – are all “spendthrift progressive” states? Tell Georgia Governor Brian Kemp, who signed the Georgia SALT Parity bill, to his face that he’s just the same as “Gavin Newsom and J.B. Pritzker.”

And the millions of pass-through business owners in those states – including manufacturers, retailers, home builders, and more – are just “wealthy denizens”? What a joke. A reader without any history here would think only “partners in law and accounting firms, hedge funds, consulting shops and physician practices “are able to deduct their business SALT,” but those businesses reflect a tiny minority of the pass-through community.

The comparison to wage earners is deeply flawed, too. SALT Parity critics often argue the policy is unfair to non-business owners, but they never back it up with any numbers. It’s true SALT Parity allows business owners to deduct their SALT – just like C corporations – but wage earners get benefits too, including tax-free retirement and health benefits, employer-paid FICA, and other advantages over the typical business owner.

The correct comparison for SALT Parity is with the corporate competition, who under the Senate bill continue to deduct all their SALT with no limitation and pay a really low, 21-percent tax rate. So Home Depot deducts its SALT, but not the hardware store around the block. CVS gets a full SALT deduction, but not your local pharmacy. It didn’t make sense in 2017, and it doesn’t make sense now. The WSJ is silent on this issue.

What they do care about, apparently, is the possibility of using the SALT Parity laws to game the system and generate federal tax deductions in excess of what the owners would otherwise pay and then use tax credits to make the taxpayer whole. While some states like Massachusetts are guilty of some version of this, the problem is wildly overstated and ignores simple fixes that would prevent gaming from taking place.

For example, the piece cites the Wisconsin Salt Parity law as a problem:

In Wisconsin, pass-throughs pay a flat 7.9% tax rate, which is higher than the state’s top marginal rate of 7.65%. Though individuals may pay more in state tax because of the workaround, they are still better off because they can fully deduct their SALT bills.

We wrote the Wisconsin law and the 7.9 percent rate had nothing to do with generating excess deductions – the state had an existing election where pass-throughs could pay at the entity level. We simply piggy-backed Wisconsin’s SALT Parity election on an existing Wisconsin provision, which meant the business would have to pay at the corporate rate – 7.9 percent. Question to the WSJ – why is a Wisconsin C corporation able to fully deduct their 7.9 percent tax, but if a pass-though does it, it’s a threat to democracy?

The entire editorial is in a similar vein, full of half-truths and massive distortions. We knew the Corporate Industrial Tax Complex has little sympathy for Main Street businesses and really hates our SALT Parity campaign, but seeing them manipulate the WSJ into publishing this ridiculous editorial is very disappointing.