Today’s House Budget Committee hearing on “Incentivizing Economic Excellence Through Tax Policy” is a good chance for members to learn about the importance of the Section 199A deduction for individually and family-owned businesses.

This deduction was enacted as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and serves two primary purposes – 1) to encourage job creation and economic growth by reducing the tax burden on pass-through businesses and 2) to ensure tax parity between pass-throughs and C corporations with their lower, 21-percent rate.

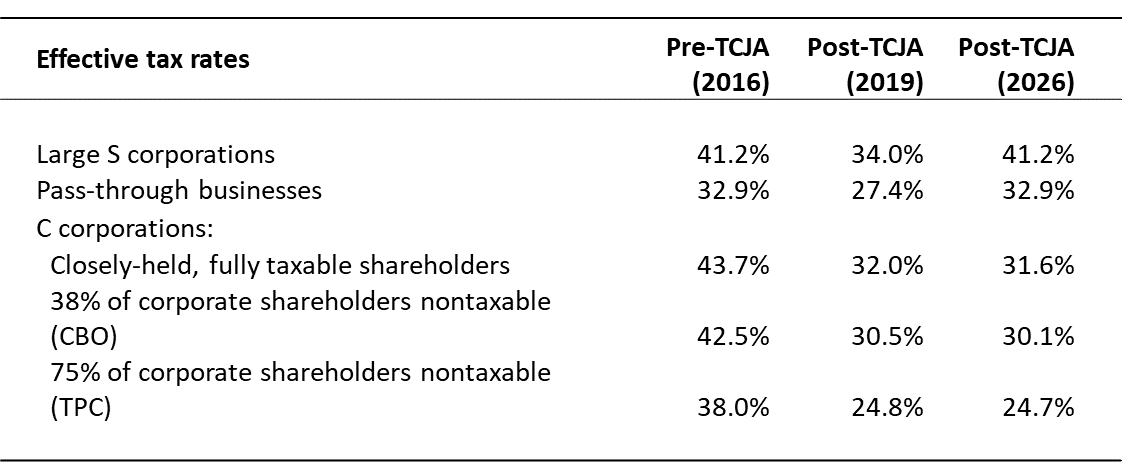

Did it work? A new study by Robert Carroll at EY suggests that a rough parity between business types does exist, but only roughly and only as long as 199A remains in place. As you can see in the table below, public C corporations pay somewhere between 25 and 31 percent effective tax rates, depending on the assumptions you make as to their shareholder makeup. All pass-throughs, on the other hand, pay around 27 percent, while large pass-throughs pay 34 percent.

The deduction is set to sunset beginning 2026, however, at which point family-owned businesses will be forced into a Hobson’s choice – remain in their pass-through form and pay rates 16 percentage points higher than the competition or convert to C status and be forced into the double tax. Either way, Bob’s table shows private companies pay more than their public company competition.

The new EY study follows in a long line of studies emphasizing the importance of 199A to Main Street competitiveness and parity, including:

As former Joint Committee on Taxation Director Ken Kies concluded, “Current law section 199A should be retained in its entirety. Doing so will still leave passthroughs more heavily taxed than C corporations, but removing any of the benefits of section 199A will only make the disparity worse.”

For members of the Budget Committee, here are a few questions to ponder during their hearing:

What About the Double Tax?

A key difference between pass-through taxation and the classic corporate form is the double tax that applies to C corporations. The corporation pays an initial tax (21 percent) when the money is earned, and then a second tax may be applied when the company pays a dividend or its shareholders sell the stock. This contrasts with pass-throughs, who pay a higher rate initially (37 percent), but there’s no second layer of tax. The problem with the double tax on corporations is multifold. It raises the effective rate on those businesses, and it results in a remarkable amount of distortion as businesses and their shareholders change their behavior to avoid the second layer.

In recent years, however, the percentage of C corporation shareholders who are tax advantaged – they either pay no taxes at all (charities, endowments) or pay greatly reduced rates (qualified retirement accounts, foreign shareholders) — has increased dramatically. In the sixties, four out of five shareholders paid the full tax. Today, the Tax Policy Center estimates that three out of four pay no tax or greatly reduced rates. Bob’s study addresses this variable by providing alternate results depending on competing profiles of shareholders. So a C corporation with fully taxable shareholders (say an S corporation that converted to C) would pay an effective rate of 32 percent, while a public company with 75 percent tax-advantaged shareholders would pay only 25 percent. That’s a huge difference and it suggests the old corporate double tax is of decreasing importance when measuring the tax burdens of public companies.

What about the Size of Companies?

Another key consideration raised by Bob’s work is the importance of taking business size into account. Too often, economists will compare the overall tax paid by C corporations to the overall tax paid by pass-throughs, only to find that the pass-through rate is less. But pass-through businesses tend to be much smaller and less profitable, while nearly all reported C corporation income comes from the few thousand companies listed on the public exchanges. In other words, failing to adjust for size does little more than point out that very large public companies tend to pay higher rates than very small private ones. Duh. (The irony here, of course, is that nobody is suggesting raising rates on smaller pass-through businesses, even as some use those low reported rates as an excuse to hike taxes on large pass-throughs.)

To adjust for this, Bob separated out large S corporations (those subject to the individual top rate) so that a large v. large comparison can be made. As the table shows, large pass-through businesses paid higher rates before the TCJA, they pay higher rates now, and they will pay really high rates if the 199A deduction is allowed to expire.

Why Can’t They Just Convert?

Which brings us to the usual response from critics – why can’t large S corporation just convert? Again, Bob’s table shows that private companies that convert will still pay higher rates than public companies. That is because, by definition, all S corporation shareholders are taxable, and therefore the converting company would face the full brunt of the double corporate tax. In the table, compare today’s rate on large S corporations (34 percent) with the fully-taxable rate (32 percent) they would pay if they converted, versus the rate (25 percent) the public company pays. Either way, the private company pays more.

This brings up an important point – the way to divide the business community is not between large and small. Such comparisons are artificial and immediately devolve into debates over what qualifies as “small.” Instead, a better demarcation is between public and private companies. A large private company has more in common with a smaller pass-through than it does with a similar-sized public company. Their governance and management challenges are completely different. Most importantly, the public company has access to relatively inexpensive money in the public equity and debt markets whereas the private company’s options are usually limited to the family’s assets and bank loans.

Where are the Jobs?

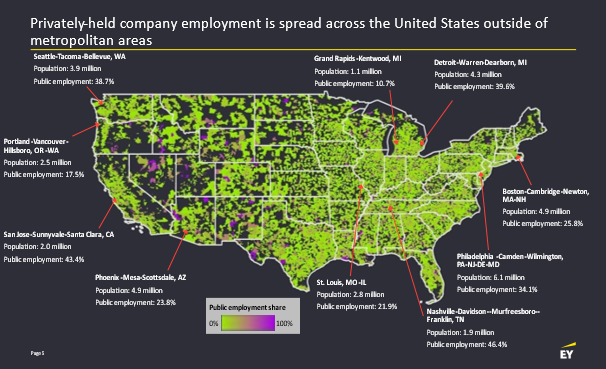

This final question is the key to the whole debate. Private companies organized as pass-through businesses employ 58 percent of all private sector workers. When the Budget Committee debates the importance of economic growth and job creation, they need to start with the pass-through sector, since that’s where the jobs are.

This question has geographical implications too. An earlier EY study showed that while most public company jobs are located on the coasts and in city centers, private company employment is both larger (80 percent of all jobs) and more evenly spread around the country.

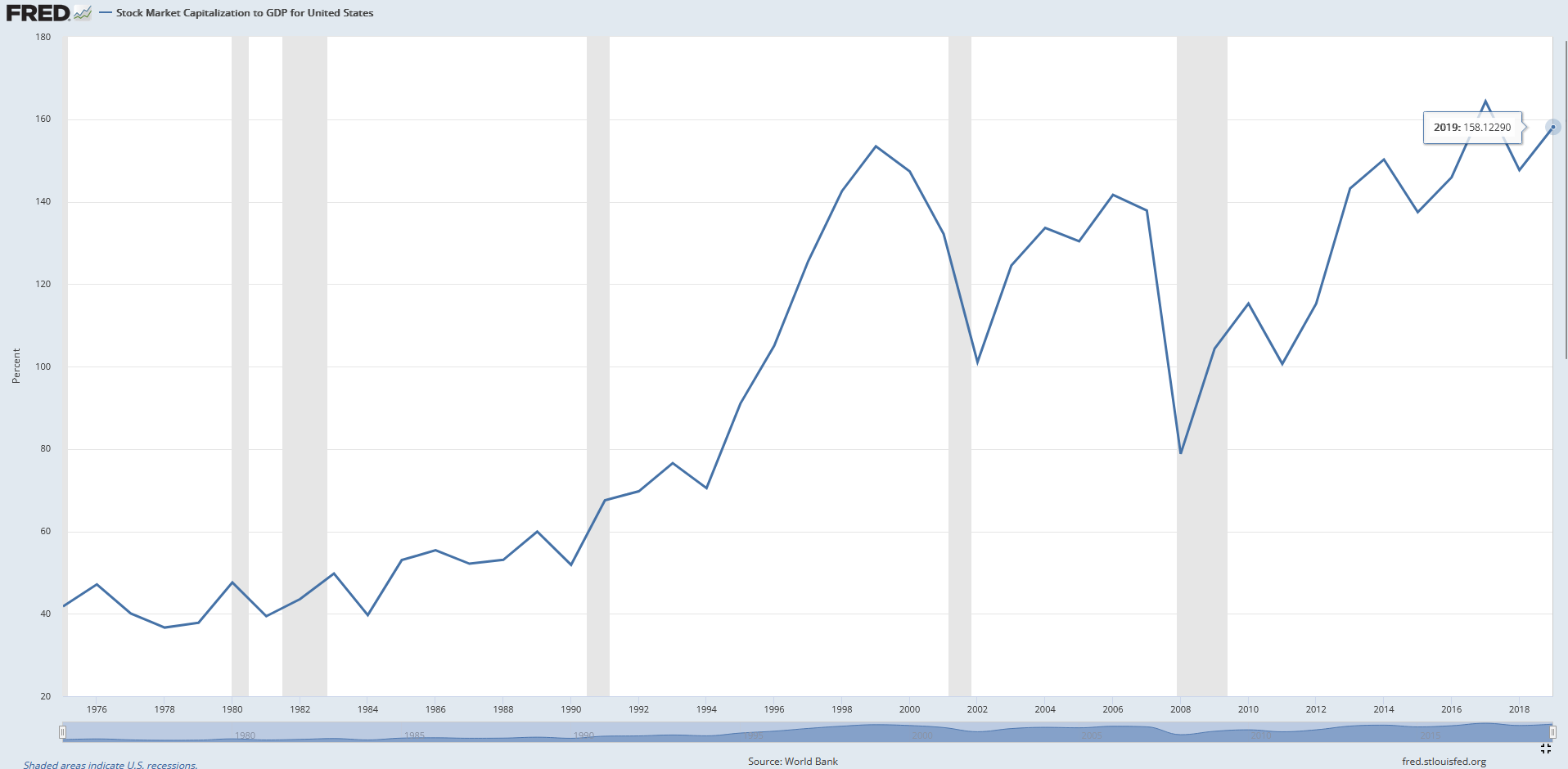

Entire communities (and even states) depend on private company employment for their economic base. Congress needs to ensure that the Tax Code doesn’t hurt the ability of these companies to survive. That won’t be easy, as the trend in recent decades has been going in the other direction — towards market consolidation within the public company space.

As this graph from the St. Louis Fed shows, the market cap for companies traded on US public exchanges (public C corporations) has increased from less than 100 percent of GDP in the 1990s to around 160 percent of GDP today. Economic decision-making is being concentrated into fewer and fewer boardrooms and away from the communities who will be affected by the decisions. There are many factors causing this concentration – the Tax Code shouldn’t be one of them.

Conclusion

The 199A pass-through deduction is the only tax provision protecting thousands of local communities from fewer jobs and more boarded up buildings. It reduces the tax burden on local businesses to make them more competitive while helping to level the effective rates paid by private and public companies. Congress needs to commit to preserving these communities and these jobs by making the Section 199A deduction permanent.