The head of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) will testify tomorrow before the House Financial Services Committee (HFSC). The hearing will focus on the Corporate Transparency Act’s implementation and is a good opportunity for Congress to learn more about this trainwreck of a law and why it should be repealed.

The Corporate Transparency Act claims to target so-called shell corporations engaged in illicit transactions like money laundering and terrorism finance, but the law defines a shell company as legal entities with $5 million or less in annual revenues or 20 or fewer employees – in other words, every small business in the United States. These businesses and other entities are required to report the personal information (BOI) of their “beneficial owners,” broadly defined to include not just owners, but every senior employee, board member, and other professionals exercising “substantial control” over the business.

So starting this year, millions of small businesses will need to report the personal information of their owners and significant others to FinCEN, and then keep this information updated on a timely basis, or face thousands in fines and years in jail. In case the law’s threat of fines and felony jail time wasn’t already clear, the description of the bill related to tomorrow’s hearing should dispel any confusion:

In addition, the bill charges the Director of FinCEN to establish a method to track delinquent businesses in its BOI reporting. Once a method is established, the Director must include that delinquency number in the quarterly report. Additionally, the Director will also be required to outline the measures taken to impose civil and criminal penalties on reporting companies that are delinquent in submitting a BOI Report.

Did we say the CTA applies to small businesses only? Not so. A serious challenge to CTA compliance and enforcement is the fact that the law’s employment and revenue thresholds are measured at the entity rather than the establishment level. This is a critical distinction and its significance appears to have eluded both the drafters of the CTA and FinCEN.

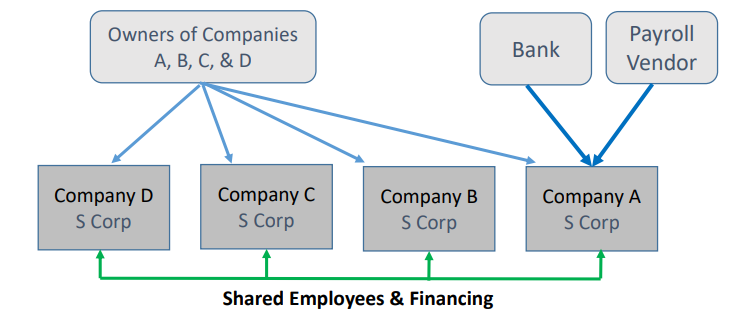

For example, you might believe the owner of a manufacturing business with $50 million in revenues and 400 employees would be too large to be a “shell” corporation and would be exempt from reporting under the CTA. You would be wrong. That is because most businesses are not organized as a single entity, but include numerous legal structures to house distinct locations and operations. We generated the illustration below to demonstrate the challenge of aggregation under Section 199A six years ago, but it applies to the CTA as well:

In our example, the business has three locations, each organized as a separate S corporation for legal and liability purposes. It also employs a fourth “administrative” S corporation that houses the payroll, contracts, bank accounts, insurance, and contracts for the business. Our reading of the CTA and FinCEN’s guidance is that the three location entities have no revenue and no employees and are required to report their BOI, as is the holding company in the tier above. This despite the fact that the enterprise as a whole has millions in contracts and hundreds of workers. It is not a “shell corporation” by any measure except under the CTA’s sloppy drafting.

It gets worse. FinCEN has been tasked with educating these businesses regarding their new reporting responsibilities, but the law’s structure makes it impossible for the agency to determine which businesses will need to report. Again, the CTA targets legal entities based on their employment, revenue, and organization. Neither FinCEN, the IRS, Secretaries of State, nor any other government agency has all this information. So how is FinCEN supposed to identify and alert – by its own estimates – 32 million entities that they need to report their BOI this year if they don’t know who to contact?

It gets even worse. The CTA creates a one-stop shopping market for cyber criminals eager to steal the critical personal information of the owners of millions of reporting businesses. Who is concerned about this danger? Here’s the warning message that’s currently emblazoned on FinCEN’s homepage:

We appreciate the warning, but the need to post it just illustrates the danger of putting all this personal information into a single federal database. It also complicates the fantasy expectations of the law’s sponsors to compel the compliance of millions of business owners who don’t know the law exists and who FinCEN can’t identify. It’s like they created the worst dating app in history, only with fines and felony convictions for failure to engage.

One last point. This whole exercise is a complete waste of time. Can somebody please ask tomorrow’s witnesses to explain how collecting the personal information of the owners and employees of 32 million small and large businesses will help identify those few engaged in illicit financial transactions? There is nothing in the collected data that would signal criminal activity to FinCEN, and the actual criminals are highly unlikely to accurately report their criminal operations. What’s a paperwork violation to somebody engaged in terrorism finance?

On the other hand, a paperwork violation that includes large fines and jail time is devastating to real business owners simply trying to make ends meet. Those owners are the real targets of the CTA, and the sooner Congress recognizes this, the sooner we can end this failed experiment.