The inequality narrative driving tax policy this year is built on three shaky foundations: (1) that the rich have captured all the economic gains in recent years, (2) that Americans support very high tax rates, and (3) that America thrived under much higher tax rates than are being considered today. S-Corp addressed the first two fallacies (here and here). A recent Senate Finance Committee hearing on how to make the tax code fair provides a good example of why the third leg is just as unstable.

The hearing featured Abigail Disney, who is part of the group Patriotic Millionaires and supports higher taxes on income and wealth. She is also the granddaughter of Disney cofounder Roy Disney and inherited a sizable fortune. According to Ms. Disney:

Corporate taxes are at an all-time low, and shameless corporate tax avoidance at an all-time high. Trillions of dollars are currently being stashed overseas in tax havens by fortune 500 companies in ways both quasi legal and potentially criminal. All of this value accrues once again to managers and to shareholders like me.

Ms. Disney provided similar testimony a few weeks ago before the Senate Budget Committee, where she made clear that, even as he built his empire, her grandfather took a very modest salary from the company:

In 1965, the average CEO made 21 times the salary of the typical employee at the company, whereas today their pay averages around 320 times. Studies of corporate efficiency, however, have not revealed anything close to a 320 times advance in efficiency, profitability, or research and development. CEOs, in other words, aren’t 320 times better than they were in the 1970’s.

So Roy Disney amassed a huge fortune despite high tax rates and paying himself only a modest salary? Something is missing here. Those who understand the history of taxation in the U.S. know the answer to the riddle. As Vox posted a couple years ago:

In the 1960s and 1970s, companies usually reinvested their profits rather than giving raises to executives — the high tax rates meant those salaries would be largely taxed away. Reinvesting the money ultimately benefited shareholders in the company by increasing the company’s value, and benefiting shareholders means benefiting rich people. Owning corporate shares was much rarer for middle-class people in the ‘60s and ‘70s before the rise of 401(k)s and IRAs.

Roy wasn’t paying himself a modest salary out of solidarity with his workers; he was doing it as a tax avoidance scheme. One of the challenges in comparing CEO compensation today to prior decades is the differing tax treatment. What’s seen as an era of more reasonable CEO pay can just as easily be explained as an effort to minimize tax bills.

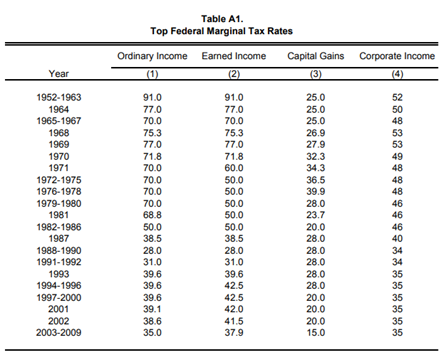

As you can see from the table, taxpayers in the 1950s had a choice of paying top marginal rates of 91 percent on their wage and salary income, 52 percent on their corporate income, or 25 percent on their capital gains income. With those choices, you’d be crazy to take your income as wages and salary.

The challenge was to shift the income someplace where it would get more favorable tax treatment. In this case, Roy and his brother Walt were building their successful empire, which meant they had a ready-made C corporation to shelter their income and build wealth.

The trick was to reinvest earnings and increase leverage to reduce the corporate income subject to tax. By reinvesting profits and borrowing to finance expansions, even profitable businesses could have little or no taxable income at the end of the year. As Phillip Magness observed:

The mid-century tax system only functioned because policy makers in that era intentionally used a complex system of exemptions, deductions, incentives, loopholes, employment-related benefits, and legal shelters for certain income sources to reduce effective tax rates well below the statutory rates.

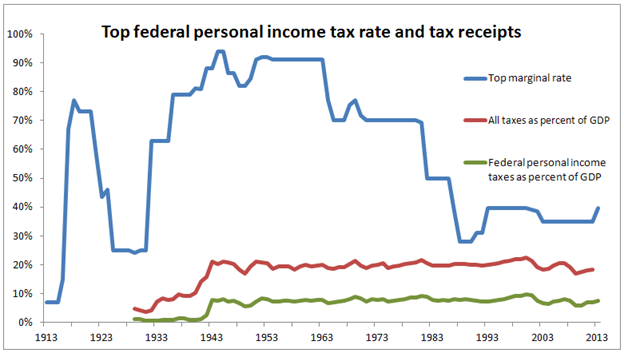

In other words, the tax code in 1950s and 60s combined extremely high rates that nobody paid with a very narrow, loophole-ridden tax base. It’s the opposite of good tax policy, and certainly nothing to emulate today. You can see the combined effects of these policies in the effective rates – the taxes that were actually paid – from those decades.

Shifting income from salaries to corporate profits and capital gains may have allowed wealthy taxpayers to keep more of their income, but it came at a cost. It was highly inefficient and resulted in decisions being made for the sake of the tax code rather than the business.

The 1986 Tax Reform Act changed all this. It lowered rates and eliminated many of the loopholes and other provisions used by the wealthy to avoid taxes and to amass their fortunes. As S-Corp Advisor Tom Nichols told the Ways & Means Committee years ago:

In this regard, the bipartisan Tax Reform Act of 1986 stands out as an excellent template for Tax Reform. It expanded the tax base by eliminating numerous preferences and privileges for specific taxpayer groups, thereby creating room to dramatically decrease the tax rates for C corporations, pass through businesses and individuals alike. This approach allowed many, if not most, owners and managers to get out of the tax planning business and immerse themselves in the operations of their real businesses instead.

Now, motivated by questionable economic studies and a desire to punish success, the Biden Administration wants us to return to the pre-1986 days where corporate tax shelters dominated the economic landscape. It won’t help address real economic disparities, it won’t be good for family businesses, and it won’t be good for America.