The key debate before Congress next year is how to tax large, family-owned businesses. There is no debate over how to tax smaller businesses. Nobody on the left or right is arguing to raise taxes on small businesses.

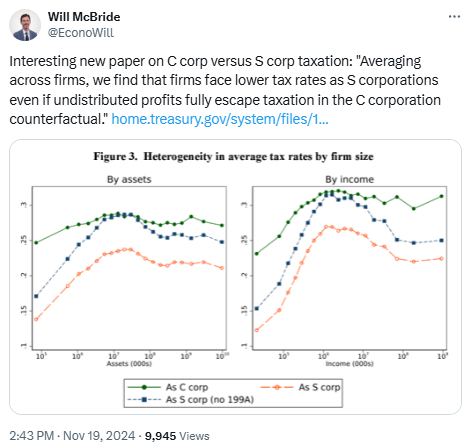

This reality is lost, once again, on the tax experts. For example, several economists at Treasury are out this month with a new paper on business tax rates and our friends at the Tax Foundation have already flagged it with misleading tweets:

A casual reader would conclude the Treasury paper demonstrates that S corporations pay less than their corporate competition, even when looking at larger businesses. Not so.

Instead, the paper looks at the same “horizontal” equity trap as previous works. Horizontal equity is where you measure how similar firms are treated under the Tax Code, depending on how they are organized. So a particular firm might pay one tax level as an S corporation, and another level as a C corporation. For example, the paper states:

Furthermore, we find spikes in mass around 11 percentage points (Panel A) and 9 percentage points 10 (Panel C), corresponding to the set of firms whose owners are in the 12% ordinary income tax bracket – e.g., joint filers in 2018 with ordinary taxable income between $19,050 and $77,400. For these firms, the S corporation ATR is 12% without Section 199A and 9.6% under current law, while the C corporation ATR is often exactly 21%, as these firms typically do not have GBCs, and their owners face a zero marginal tax rate on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends. Given that these firms tend to have relatively low income, these spikes do not appear nearly as visibly in the dollar-weighted panels.

Translated, small business owners in the 12-percent tax bracket pay less as an S corporation than as a C corporation. But everybody knows that, and it has nothing to do with the tax debate.

The real question is: Can family businesses compete with public C corporations when the corporate rate is 21 percent? Horizontal equity doesn’t apply here for the simple reason that family businesses can’t become public companies, as that would require them to sell the business. Lots of S Corp members have done just that in recent years, with the result that they are no longer family-owned businesses.

For an answer to that question, our EY study continues to be the best resource. It shows rough parity between large S corporations and public companies with 199A in place, but no parity without it.

Adverse Selection: The paper looks at the taxes paid by S corporations, and then measures what they would pay as C corporations. Not surprisingly, the study finds that most – not all – businesses currently organized as S corporations would pay more if they converted. But what if the authors started with the private C corporations and measured how much they would pay if they converted to S corporations? If they pay less, why are they C corporations?

ESOPs: The study includes ESOPs in its averages, which drives down the averages for S corporations and C corporations alike: “If there is no match to any of these tax returns, we assume that the owner is an employee stock ownership plan (ESOP)…. We assume income flowing to ESOPs is entirely untaxed (whether the firm is a C corporation or an S corporation).”

Behavioral Changes: We have long argued that 199A revenue estimates need to include significant behavioral adjustments. The authors agree: “[I]f the law were to change such that all large S corporations were now taxed as C corporations, there would be substantial behavioral effects given the new tax regime, including businesses re-structuring, changes in payout rates, and potentially changes in the wages paid to owners. We have abstracted away from such matters, for the most part. Therefore, our estimates do not correspond to revenue estimates for such a policy change.”

Finally, there is this:

To some extent, these findings depend upon the values of the payout rate () and the deferral/avoidance parameter () that affect the C corporation counterfactual. On the one hand, a simple average across firms results in lower ATRs for S corporations relative to the C corporation counterfactual, regardless of the values of and and regardless of Section 199A. On the other hand, if we give more weight to higher-income firms, reflecting their greater economic importance, then there are some values of and that yield lower ATRs in the C corporation counterfactual. Relative to current law, only values of and quite close to zero would suffice (see Figure 8). Relative to the no-199A counterfactual, if we set = 0.28 (the average payout rate for similarly sized C corporations), then retained earnings would need substantial benefits from deferral to result in lower ATRs in the C corporation counterfactual. [Emphasis added.]

Translated, they are saying 1) smaller S corporations drive down all their averages and 2) larger pass-through businesses that pay out 28 percent or more of their after-tax profits are screwed regardless of how they are organized. We’ve been making that point repeatedly as well.

How to conclude? “Get ready” is what we say. The Corporate Tax Industrial Complex (CTIC) is in full swing and you can expect many more studies like this, coupled with sounding board tweets, panels, webinars, etc. As noted, this study says little to nothing about the debate before Congress, but that won’t stop them from trying to make you think it does.