A recent Twitter thread caught our eye. S-Corp typically avoids these Twitter feuds, but this is an important topic that deserves some clarity. Here’s the thread in question:

So Pomerleau thinks 199A is unnecessary while S-Corp and our Main Street Employers Coalition have long maintained that 199A is necessary for rate parity. Who is right?

Effective Statutory Tax Rates

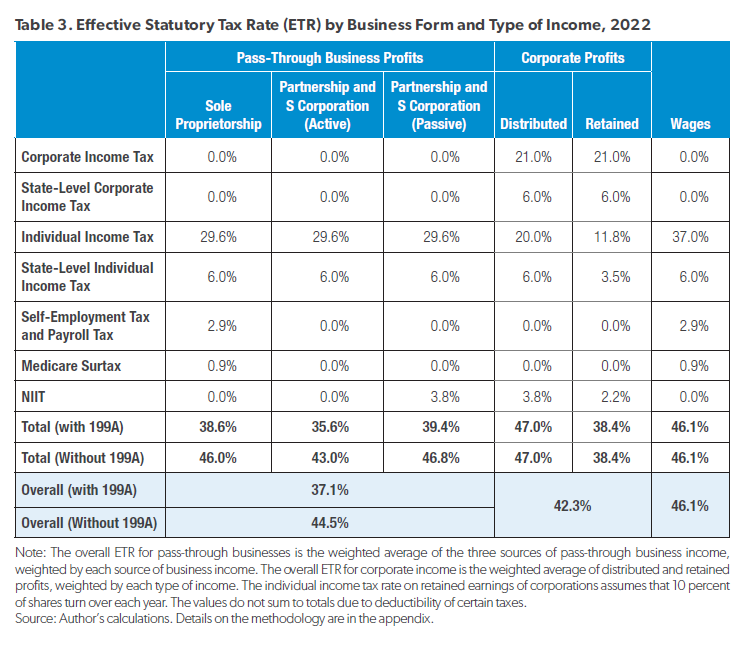

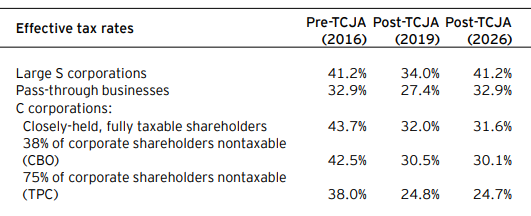

Looking at Pomerleau’s paper, he uses three measures to examine the parity question – Effective Statutory Rates, Marginal Effective Tax Rates, and Average Marginal Effective Tax Rates. For the first, here’s his table:

For somebody who has been advocating hard to eliminate Section 199A (here, here, here… you get the idea), this is pretty weak sauce. We believe the current rates represent rough parity and here it is — the average pass-through rate is somewhere in the low-40s and the average C Corp rate is somewhere in the low-40s. Close enough for tunnel work.

Moreover, the table tends to underestimate the pass-through rates and inflate the corporate ones. For starters, not all large pass-throughs get the full 199A deduction. That’s because 199A includes guardrails that limit the deduction. Treasury estimates these guardrails reduce qualifying 199A income by about 40 percent, so the starting rate for a large pass-through that otherwise qualifies for 199A can easily be higher than 29.6 percent.

Meanwhile, the estimates for the second layer of corporate tax look inflated too. As we’ve noted, most public corporation shareholders pay little or no federal tax, and very few corporations pay significant dividends. The paper acknowledges this, but the “Distributed” column still assumes shareholders are fully taxed. The “Retained” column is inflated too, as the tax on capital gains should be reduced to account for exempt shareholders and those gains held until death. Here is a 2016 CRS description of the issue:

A Congressional Research Service (CRS) study estimates that the average tax rate at the margin on dividends is 14.7% and the average for realized capital gains is 15.4%. Half of capital gains are estimated not to be subject to tax because the gains are passed on at death, and thus the effective tax rate is 7.7%. Weighting the two tax rates by their estimated income shares results in an overall individual shareholder tax averaging 11.6%.

The 11.6% is not the additional tax, since it is applied to income net of the corporate tax rate. As will be discussed subsequently, this rate should be the effective corporate tax rate, which varies by investment; if corporate profits were taxed at 35%, the additional tax would be 11.6% times (1-0.35), or 7.6%

Another thing. Next year’s debate isn’t just about 199A. The rates that apply to pass-through income are also scheduled to go up. The paper doesn’t address this challenge, even though Pomerleau appears to support allowing the top rates to return to their pre-TCJA levels.

Finally, the table excludes any effects of the SALT cap. Pass-through income is subject to the cap but C corporation income is not. The paper notes that S-Corp has been successful with our SALT Parity efforts and that many pass-throughs now enjoy an election to restore the deduction. But those changes are by no means universal, and they definitely weren’t part of the original plan.

Showing rough parity despite having all the table’s biases leaning against the pass-through sector is just not a very convincing start.

Uniform Capital Weights and…

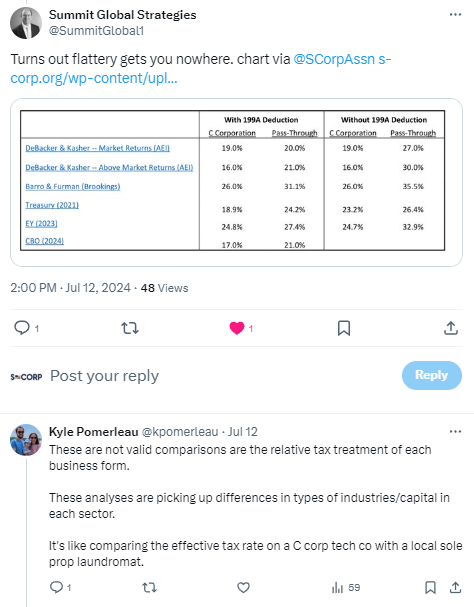

Next, Pomerleau looks at Marginal Effective Tax Rates (METRs) and Average Effective Tax Rates (AETRs). This is the core of the twitter thread:

The studies from Treasury et al listed there clearly show we achieved rough rate parity with Section 199A but that it disappears along with the deduction. That’s the question in front of us, isn’t it? Under the TCJA, who pays what?

Pomerleau objects. It appears his preferred analysis would focus on horizontal equity – a comparison of how much tax the same business would pay if it were organized under different forms. Here is his explanation:

[T]his report seeks to compare the tax treatment of pass-through businesses and C corporations. To do that, differences that arise due to underlying economic parameters were eliminated. The ETRs on different types of business income were calculated assuming that the distribution of each form of business income has the underlying distribution of total business income. The distribution of the capital stock for each business form was assumed to be the distribution of all business capital. Other parameters, such as the share of new investment financed by debt, the real after-tax return, and the inflation rate, were also held constant across business forms. As a result, the differences in effective tax rates only reflect differences in tax treatment.

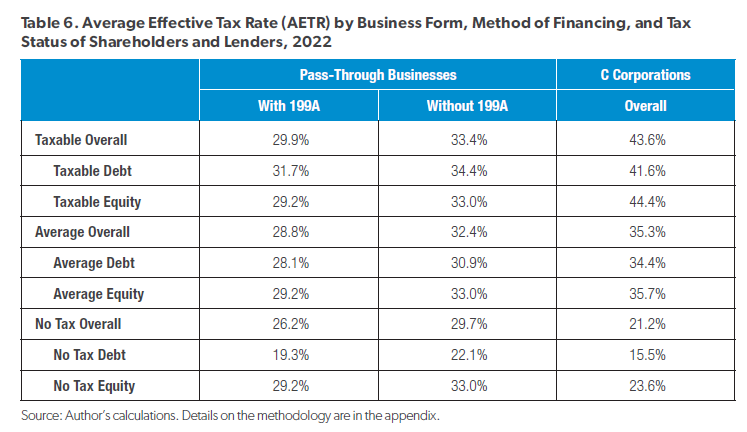

Horizontal equity has its uses but it is not the only valid comparison and it is very limited in what it tells us. Effectively, the paper substitutes calculations that reflect actual investment levels and tax burdens with a narrower view that assumes all businesses operate exactly the same. Not very realistic and not very transparent.

For example, Table 6 says a closely-held business would pay an AETR of 29.9 percent as a pass-through with 199A, 33.4 percent without 199A, and 43.6 percent as a C corporation. A reader might infer that this means that generally, pass-throughs pay less, but that’s not accurate. Instead, all we learn is that a hypothetical family business whose shareholders are subject to the top rates either can pay 29.9 percent as a pass-through or 43.6 percent as a C corporation.

What they cannot do, and where the unfairness lies, is access that 21.2 percent rate that applies to public C corporations only. That is what Table 6 tells us.

New v. Old Investment

Another challenge is the paper (as with the similar CBO paper it references ) looks at new investment only and ignores the trillions of dollars of business capital already in place, earning income, and paying taxes. The typical defense here is that tax policies should be forward looking and not “reward” existing investments with lower rates. A couple of problems present themselves, however.

First, focusing on new investment exclusively while advocating for tax hikes elsewhere begs the question: Where will the new capital come from and where will the old capital go? Progressives like expensing and other new investment incentives because they can solicit corporate contributions while calling for tax hikes on everybody else. That might be a sustainable model for think tanks, but it is not sustainable for businesses. The money for new investment has to come from somewhere, and it won’t be available if Congress taxes it all away.

Second, focusing exclusively on new investment raises the question of what constitutes new investment. S-Corp has lost a number of members in recent years, often when a mature family business is purchased by a larger public company. Economically, nothing has changed — the business is the same, as are the assets. But the sale enables the business to receive an increased basis, while the TCJA’s more generous expensing rules enable the new owners to write off the new basis at faster rates. The corporate buyer has an advantage not because they are better managers, but because the tax code treats their new ownership more favorably.

It’s all About the Rates

Relying on his narrow analysis, Pomerleau makes claims like this:

Extending current policy without Section 199A would improve the tax code’s neutrality. Under this policy, pass-through business profits would be taxed more in line with other forms of income. However, pass-through business investment would still face a lower tax burden than C corporate investment.

As we’ve pointed out, that claim simply doesn’t hold water if you are comparing the average tax burdens of public companies verses pass-throughs:

| With 199A Deduction | Without 199A Deduction | |||

| C Corporation | Pass-Through | C Corporation | Pass-Through | |

| DeBacker & Kasher — Market Returns (AEI) | 19.0% | 20.0% | 19.0% | 27.0% |

| DeBacker & Kasher — Above Market Returns (AEI) | 16.0% | 21.0% | 16.0% | 30.0% |

| Barro & Furman (Brookings) | 26.0% | 31.1% | 26.0% | 35.5% |

| Treasury (2021) | 18.9% | 24.2% | 23.2% | 26.4% |

| EY (2023) | 24.8% | 27.4% | 24.7% | 32.9% |

| CBO (2024) | 17.0% | 21.0% | ||

Moreover, we are not sure that Pomerleau is correct within the narrow confines of horizontal equity. Our EY study shows that a closely-held business does better as a C corporation post-cliff — still worse than the public company, but better than the pass-through.

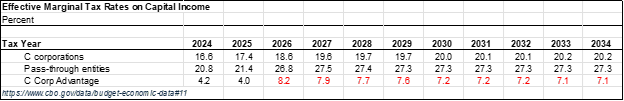

And here are the Effective Marginal Tax Rate estimates used by the CBO right now for their modeling – they show C corporations having a slight advantage with 199A in place and a much larger advantage without it.

It appears that Pomerleau is an outlier here.

Reality v. Spreadsheets

In the Twitter thread that started all this, somebody asked if we had seen significant conversions of S corporations post-TCJA. The answer is yes, a number of our members converted post-TCJA and we expect to lose many more if we go over the fiscal cliff.

S-Corp’s remaining members are well aware of what’s coming and they are waiting to see what happens. These are large, sophisticated family businesses with long-term planning horizons and the means to model out multiple policy outcomes.

The irony is that Pomerleau’s favored approach is exactly the analysis they are conducting. It tells them what their effective tax rates are under the current rules, and what they might be as S corporations and C corporations under the various fiscal cliff outcomes.

What it doesn’t tell them is how their situation compares to public companies. That analysis has been done by Treasury, CBO, EY and others, and it shows the public companies will continue to have a distinct advantage. That’s the threat of the fiscal cliff, and that’s why Congress needs to make permanent the 199A deduction.