Actual tax policy remains on hold in Congress (listen to our recent “Talking Taxes in a Truck” for that discussion) but there’s been some activity in recent weeks that’s worth highlighting nonetheless. Specifically:

- Yesterday’s Finance hearing entitled, “Examining How the Tax Code Affects High-Income Individuals and Tax Planning Strategies”

- Wednesday’s Senate Budget hearing entitled, “Fairness and Fiscal Responsibility: Cracking Down on Wealthy Tax Cheats”

- A new Auten/Splinter paper examining income inequality and income shares

Here’s a quick summary of each and how it is all related to pass-through taxation. Kind of like six degrees of separation minus Kevin Bacon.

Senate Finance

Yesterday’s Senate Finance hearing was an obvious effort to rationalize why unrealized gains should be part of the tax base. As the Chairman argued:

Today, we’ll examine one strategy – among others – called “Buy Borrow Die.” Just three little words on the chart behind me, that have a huge impact. Here’s how it works: A corporate raider buys a business, and then borrows against its growing, untaxed value to fund their extravagant lifestyle. Everything from superyachts, to luxurious vacations, expensive art deals, you name it. It goes up and up in value all while not paying a dime in tax. And when they die, their assets are passed to their kids – often entirely tax-free – and the cycle continues.

Is any tax avoidance plan where the taxpayer has to die really that great? We prefer to stick around to enjoy our excessive after-tax income. Also, why does the Chairman sound like Robin Leach?

More to the point, how exactly does “Buy, Borrow and Die” work? First, a taxpayer (corporate raider) needs lots of appreciated stock. Second, the stock can’t be spinning off income, as the taxpayer would just use that to fund their (extravagant) lives. Think growth rather than value. Finally, the taxpayer borrows against the appreciated value of the stock.

Couple questions. Doesn’t the shareholder have to pay interest on the loan, and aren’t those interest payments taxable? While yesterday’s witnesses argued the stock’s appreciation always exceeds the interest so the benefit is permanent, the simple reality is that stock prices fall too, even for rich people. When they do, won’t the loan’s covenants demand repayment? When exactly does the loan get repaid, and how does the taxpayer pay it? Finally, doesn’t this trade lower capital gains taxes for higher taxes on interest? Is that a good deal?

Perhaps there are other, non-tax reasons the owner of a high-flying corporation might avoid selling their stock, such as SEC reports or the impact the sale might have on the stock’s price or the owner’s control of the company? Things like that.

And where is the corporate tax in all this? When Warren Buffett claimed he paid less taxes than his secretary, he left out the fact that his company paid billions in corporate tax. Yesterday’s witnesses with the exception of Doug Holtz-Eakin) did the same. Also, what about charitable donations of appreciated stock? Such donations are probably the dominant method wealthy taxpayers use to reduce their income taxes.

These issues didn’t come up because they don’t further the cause of taxing unrealized gains. Chairman Wyden has for years advocated for a mark-to-market approach (here). To get it enacted, however, he needs to 1) build political support for the idea and 2) overcome constitutional concerns regarding the definition of income under the 16th amendment.

This week’s hearing attempts to address challenge one, while the Moore v. United States decision by the 9th Circuit – and now before the Supreme Court — presumably is designed to address challenge two.

Senate Budget

While the Finance Committee focused on legal tax avoidance to promote mark-to-market taxes, the Senate Budget Committee targeted illegal tax evasion to promote more IRS funding. According to Chairman Whitehouse:

Most Americans follow the law and pay their taxes on time and in full. Many of the very wealthiest Americans, however, play by their own rules. Empowered by a tax code that is rigged in their favor, they rob the public weal of revenue and leave everyone else to foot the bill. Today, we will hear how the super-wealthy account for a large and disproportionate share of tax evasion, and cost the American people perhaps hundreds of billions every year….

Dr. Natasha Sarin, one of our witnesses today, estimates that the top 1 percent account for 30 percent of unpaid taxes. You heard that right: one percent of the population; thirty percent of the cheating.

Robbing the weal? That sounds bad, but don’t the top 1 percent pay more than 40 percent of all income taxes? Does that mean their compliance rate is better than average? Hard to say, as the truth in all this continues to be buried in a fog of iffy estimates and IRS budget battles.

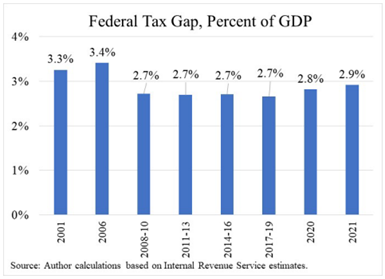

What we do know is after decades of over-the-top rhetoric and unfulfilled promises, the tax gap remains just about where it has always been. This from CATO’s Chris Edwards’ testimony:

Auten/Splinter

An S-Corp mantra is you can’t make good tax policy without good data. Underlying this week’s hearings was the premise that the rich are getting richer and we need to use tax code to rein them in.

Missing was any examination of the premise, an omission which is particularly glaring given that its chief skeptics, economists Gerry Auten and David Splinter, just released an updated version of their Piketty/Saez/Zucman take-down. It is comprehensive and devastating. Here’s the abstract:

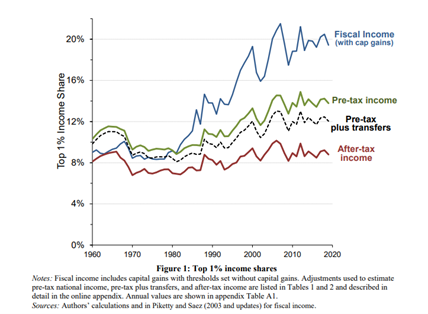

Concerns about income inequality emphasize the importance of accurate income measures. Estimates of top income shares based only on individual tax returns are biased by tax-base changes, social changes, and missing income sources. This paper addresses these shortcomings and presents new estimates of the distribution of national income since 1960. Our analysis of pre-tax income shows that top income shares are lower and have increased less since 1980 than other studies using tax data. In addition, increasing government transfers and tax progressivity have resulted in rising real incomes for all income groups and little change in after-tax top income shares.

For those uninterested in reading all 47 pages, this chart should suffice. Adjusting for changes in tax policy and other variables, the whole “the rich grabbed all the economic gains in recent decades” narrative simply falls apart.

The pass-through community is neck deep in this debate. Not only are we the target for higher taxes, but the growth of the pass-through sector post 86-TRA is a primary driver of P/S/Z’s errors in the first place. As Auten and Splinter write:

Our analysis addresses this issue by accounting for corporate retained earnings (i.e., profits after corporate tax not distributed as dividends), as well as base-broadening reforms that reduced taxshelter losses. Without these adjustments, top income shares are understated in the 1960s and 1970s, when high individual income tax rates created strong incentives to shelter income inside corporations.

So policies that improved tax transparency and enforcement back in the 1980s are being twisted to justify higher taxes on pass-throughs now. Their proposed solution, on the other hand, would simply return us to the pre-86 days of using corporations as tax shelters. Without all that income showing up on individual tax returns, its advocates could claim they made the world more equal, all while giving their corporate buddies the means to avoid the higher rates. Everybody wins, except for Main Street and the American economy.