Doug Holtz-Eakin has a thoughtful blog post this week on the deterioration of our “voluntary” compliance tax system.

Whenever the term “voluntary” is used when discussing taxes, the tendency is for the audience to bust out laughing. Okay, sure, but it’s a real concept that used to be the heart of our tax system. Rather than send tax collectors door-to-door to make collections, our system relied on taxpayers calculating their own liability and then sending in the appropriate amount.

It was fairly unique in the world yet, as Doug points out, our compliance rate consistently ranks at the top at a solid 85 percent. But as Doug observes, in recent years we have moved away from that successful model:

I used to be proud of the U.S. income tax system. It was founded on the notion of voluntary compliance and stood in stark contrast to privacy-piercing, intrusive systems around the globe. But a system of voluntary compliance relies on the broad trust that everyone is paying the taxes that are due. Over time, that trust has seemingly eroded and the U.S. system relies increasingly on “information” reports in which someone tells the IRS about someone else who earned income. The United States is now a tax nation with sub-kindergarten-level ethical norms.

As evidence of this deterioration, Doug mentions the ProPublica leaks and their attempt to paint a picture of systematic tax evasion, without ever identifying any actual evasion.

From our perspective, Doug could have just as easily pointed to the on-going fight over IRS funding. They say truth is the first casualty of war. Apparently, it also suffers when IRS funding is being discussed. Below is a summary of the recent IRS enforcement related news. Grab some popcorn, ‘cause there’s lots of it.

How Many Agents?

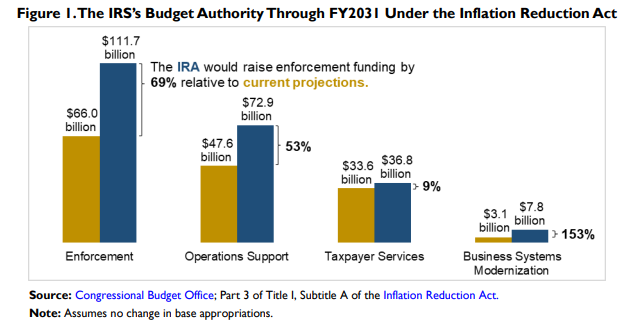

Last year’s Inflation Reduction Act included $80 billion in new funding for the IRS. The table below shows how the funds are allocated:

More than half of the new funding is earmarked for “enforcement,” which makes sense given that the funding boost was largely premised on bringing in tax revenue that would otherwise go uncollected. A document released by Treasury last year projected the new funding would enable the IRS to hire an additional 87,000 employees by 2031, with most of those new hires working on enforcement.

Republicans zeroed in on the estimate and warned taxpayers to expect to face an “army of auditors.” The media furiously scrambled to refute the claims. We were told the “87,000 agent” claim was “absolutely false”, the new hires were mostly to replace departing staff, and the funding would improve customer service and enable the agency to modernize its infrastructure. It was all very warm and fuzzy (see here, here, and here).

In response to its critics, the agency stated the net increase in its workforce would land in the 25- to 30-percent range and that the bulk of new hires would simply replace retiring ones. The IRS employed 79,000 workers in the 2022 fiscal year, so a 25-percent increase would mean 20,000 new employees. Subtract that from the 87,000 planned hires and you’re left with 67,000 new hires filling existing roles. Will the IRS really need to replace 85 percent of its current workforce in the next decade?

IRA Already Producing Results?

More confusion. Forbes reported in August that IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel credited the new funding as helping the agency boost its employment rolls in short order:

Werfel said, by using the IRA funding, the IRS has made an immediate, meaningful difference in how it serves taxpayers, including hiring new employees. While admitting hiring challenges, including ensuring that hiring keeps pace with attrition, Werfel estimates that the IRS is approaching 90,000 FTE. [Emphasis added]

Wow, that was fast. But wait, didn’t this hiring binge begin prior to the Inflation Reduction Act? Here’s a 2022 Washington Post article from before the funding was enacted:

The Internal Revenue Service plans to hire 10,000 employees in a push to cut into its backlog of tens of millions of tax returns by recruiting for jobs across the agency that have gone unfilled for years, according to four people familiar with the plan. The agency will accelerate recruiting in the coming weeks for 80 distinct positions, from entry-level clerical workers to advanced engineers and tax attorneys, one person familiar with the plan said. [Emphasis added]

We were told the decline in IRS staffing was due to a lack of funds – hence the $80 billion in IRA funding. Exactly how was the IRS planning to hire 10,000 additional employees back in March of 2022 if they didn’t have the funding?

The confusion extends to tax enforcement. Reasonable people believe it will take years for new hires funded by the Inflation Reduction Act to have an impact. It takes time, after all, to find the right candidates and more time to get them trained. Not so, says the IRS! Just one year in and we are told it’s already paying off:

IRS Ramps Up Tax Enforcement for Millionaires: IRS tax enforcement led to the collection of $38 million from tax-evading millionaires. But the agency isn’t done making the wealthy pay up.

Exactly where did this windfall come from?

The IRS allocated some of its funding from the Inflation Reduction Act to tax enforcement, and tax-evading millionaires and billionaires are targets. The agency has already closed approximately 175 delinquent tax cases, resulting in a $38 million payday for the U.S. government. With billions of dollars of potential IRS funding on the line (some of which Republican lawmakers have clawed back), the agency is motivated to continue tax collection efforts against the wealthy, and the IRS is nowhere near done.

Targeting “tax-evading millionaires and billionaires” sounds impressive, but $38 million is a drop in the bucket. Moreover, it’s not clear when these cases were opened and if the new IRA funding in fact played a role.

More Enforcement, Fewer Collections

Under the heading of “you can’t make this stuff up,” at the same time the IRS was plugging its new enforcement efforts the GAO was reviewing the agency’s audits of large partnerships. They audited 54 large partnerships in 2019 and (if we are reading this correctly) lost money doing so. Here’s the GAO:

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audits few large partnerships—54 in tax year 2019—and the audit rate has declined since 2007. More than 80 percent of the audits resulted in no change to the return on average from tax years 2010 to 2018, double the rate of large corporate audits. For those that did change, the average adjustment was negative $264,000. [Emphasis added]

Reminds us of the old joke about the entrepreneur who was losing money on every sale but planned to make it up through volume.

Here’s a question: If the IRS loses money targeting just a handful of large partnerships, how are they going to collect an additional $200 billion through expanded enforcement? The answer, apparently, is to do more of the same. You know, volume. Last month, the IRS unveiled a new “special pass-through” compliance arm that will focus on large and complex entities, along with the staffing of 3,700 new enforcement agents. According to the Commish:

“This is another part of our effort to ensure the IRS holds the nation’s wealthiest filers accountable to pay the full amount of what they owe,” said IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel. “We are honing-in on areas where we believe non-compliance among our wealthiest filers has proliferated over the last decade of IRS budget cuts, and pass-throughs are high on our list of concerns. This new unit will leverage Inflation Reduction Act funding to disrupt efforts by certain large partnerships to use pass-throughs to intentionally shield income to avoid paying the taxes they owe.

Somebody should send Commissioner Werfel a copy of the GAO report.

Conclusion

Which brings us back to Doug’s blog post and the future of tax enforcement. Doug ends his post with a call for tax reform that restores our former, less intrusive approach:

The upshot is that the voluntary compliance regime is in tatters. It strikes me that one of the primary goals of any new, broad-based tax law should be to put in place a system that supports the return to a less police-state approach to tax collection. That’s an ambitious goal, particularly for a Congress that cannot yet gavel itself into session with any reliability, but a noble one nonetheless.

We agree.

In the meantime, what can Main Street expect from an IRS that’s flush with cash and has a mandate to bring in billions of new tax dollars? As we explained in an earlier post, all signs point to more audits across the board – despite pledges to steer clear of those earning less than $400,000 – and more press releases from the IRS. Given what we already know about collection rates and the so-called tax gap, it’s unlikely these enforcement efforts will hit their intended goal, but that won’t stop them from trying.