The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has kicked off a rigorous debate over the $80 billion in new funding for the IRS. Republicans argue the funds will be used to audit the middle-class while the Biden Administration assures us that nobody under $400,000 will see increased audit “rates.”

So where does the truth lie? In short, the IRA will substantially increase the number of IRS audits over the next decade, including higher numbers of audits for middle-income taxpayers and Main Street businesses. Here’s the breakdown.

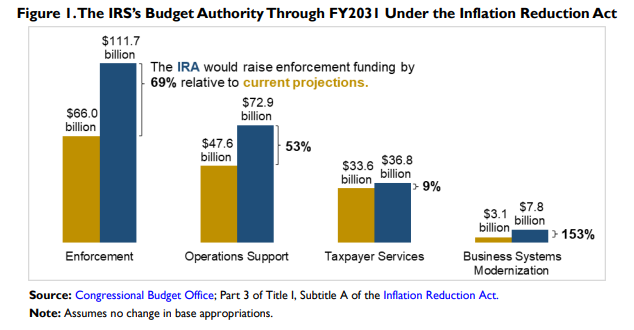

The IRA allocates some $80 billion over the next decade in additional funding to the tax-collecting agency, with more than half of that going towards what the bill describes as “improving taxpayer compliance.” The Congressional Research Service has a handy chart that shows how the money is divvied up:

Those new “enforcement” dollars are supposed to reduce the so-called tax gap, or the annual difference between what Americans should pay versus what the IRS brings in. The premise is that there’s a treasure trove of uncollected money out there, but the IRS lacks the resources to chase it all down.

This notion is pure fiction, as we’ve discussed in the past. Let’s say the annual tax gap is around $600 billion annually (the estimate keeps changing, it’s based on old data, and the whole thing is highly questionable, so we’ll stick with a round number) while congressional scorekeepers estimate the $45.7 billion in new IRA enforcement funding will raise an additional $204 billion in gross revenue.

That’s just 3 percent of the tax gap over the next decade. By that math, Congress would need to give the IRS an additional $1.5 trillion and hire hundreds of thousands of additional employees to close the entire gap. That’s obviously ridiculous, so perhaps the tax gap is not the treasure trove tax collectors think it is?

Worse, the new funding will result in a massive increase in IRS enforcement activity. As many Republicans have pointed out, a document released by Treasury last year projects the new funds would enable the IRS to hire an additional 87,000 employees by 2031.

The IRS currently employs about 80,000 workers, so the IRA would effectively double its workforce, yes? That’s what the CBO thinks:

Spending would increase in each year between 2021 and 2031, though the highest growth would occur in the first few years. By 2031, CBO projects, the proposal would make the IRS’s budget more than 90 percent larger than it is in CBO’s July 2021 baseline projections and would more than double the IRS’s staffing. Of the $80 billion, CBO estimates, about $60 billion would be for enforcement and related operations support. [Emphasis added]

But Treasury is pushing back, arguing that some of these new employees would replace retiring workers. They claim the actual increase in workers will be just 25 or 30 percent. That estimate, however, is inconsistent with Treasury’s own estimates back when they first proposed the $80 billion funding hike:

Because the expansion in the IRS’s budget is phased in over a 10-year horizon, each year the IRS’s workforce should grow by no more than a manageable 15%. By the end of the decade, however, the IRS’s budget would be roughly 40% above 2011 levels in real terms as a result of this proposal.

In 2011, the IRS had nearly 100,000 workers, so a forty-percent increase would translate to 140,000 workers. Not the doubling estimated by the CBO, but way more than Treasury is telling people now. Treasury needs to get its story straight.

Obfuscation aside, what is clear is that thousands of new IRS employees will be engaged in enforcement activities that result in higher numbers of audits – that’s where the additional $204 billion comes from, after all. Here’s the New York Times inadvertently highlighting our concerns:

The I.R.S. is beefing up its staff to keep pace with the growth in taxpayers and to replace departing employees. The Biden administration expects that about 50,000 I.R.S. employees will retire within the next decade and that the agency will hire 87,000 new employees, bringing the overall size of the agency to around 120,000. The number of enforcement agents is expected to double to about 13,000 from 6,500 over the next decade.

So you’re significantly increasing the overall size of the agency over a short time period and doubling the number of enforcement agents, even as you replace many of the existing auditors with younger, less experienced auditors? No, nothing to worry about here. Bottom line is it’s simply incorrect to argue there will not be a substantial increase both in the number of auditors or audits under the new law.

What about the argument that only taxpayers and businesses over certain income thresholds will see increased activity? We’re seeing lots of obfuscation there too, and it stems from a letter Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently wrote to senators:

These resources are absolutely not about increasing audit scrutiny on small businesses or middle-income Americans. As we’ve been planning, our investment of these enforcement resources is designed around the Department of the Treasury’s directive that audit rates will not rise relative to recent years for households making under $400,000.

And here’s the directive letter to IRS Commission Chuck Rettig:

Specifically, I direct that any additional resources—including any new personnel or auditors that are hired—shall not be used to increase the share of small business or households below the $400,000 threshold that are audited relative to historical levels. This means that, contrary to the misinformation from opponents of this legislation, small business or households earning $400,000 per year or less will not see an increase in the chances that they are audited.

First, this directive is pure political theater. Just as no Congress can tie the hands of a future Congress, no Treasury Secretary can tell the IRS what to do once she’s left office. Yellen likely won’t be in a position to enforce these demands in a year or two, let alone in 2031.

But what about while she’s in office? Notice her use of weaselly phrases like “audit scrutiny” and “audit rates” and audit “share” and increased “chances” and “existing resources” and “historic levels.” What exactly do those words mean? They mean the number of audits on households making less than $400,000 is going to increase, that’s what they mean. Here’s the CBO’s summary:

The proposed increase in spending on the IRS’s enforcement activities would result in higher audit rates than those underlying CBO’s baseline budget projections. Between 2010 and 2018, the audit rate for higher-income taxpayers fell, while the audit rate for lower-income taxpayers remained fairly stable. In CBO’s baseline projections, the overall audit rate declines, resulting in lower audit rates for both higher-income and lower-income taxpayers. The proposal, by contrast, would return audit rates to the levels of about 10 years ago; the rate would rise for all taxpayers, but higher-income taxpayers would face the largest increase. [Emphasis added]

This assessment is consistent with a subsequent preliminary score of the Crapo amendment 5404, which revealed that 10 percent of the projected new revenues come from taxpayers making less than $400,000. How could that be without increased enforcement?

Biden economic advisor Jared Bernstein apparently didn’t digest the nuance of all this, assuring CNBC viewers that the new IRS funding does not “touch one taxpayer under $400,000.” That’s not correct. This after claiming earlier this month that most of the IRA’s savings were “front-loaded” and therefore would help reduce inflation. That’s not correct, either.

Last year we had Ryan Ellis on the Talking Taxes in a Truck podcast to talk about this issue. He outlined the pain and heartburn that Main Street business owners experience when going through an audit, describing the day the IRS audit letter comes as “that Pepto Bismol moment.” Even audits where no new tax is owed are costly and stressful. With the Inflation Reduction Act, futures on Pepto Bismol are going up, and they are going up for everybody.