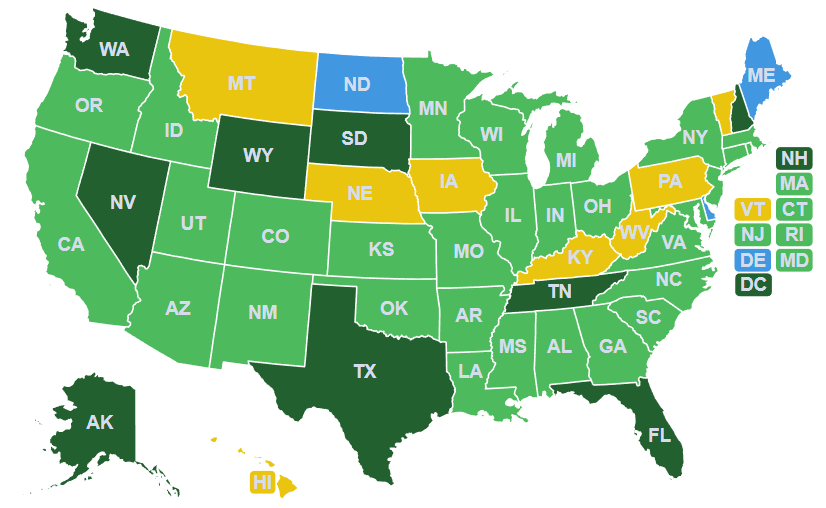

Thanks to the efforts of S-Corp and our allies over the past five years, 31 states have adopted our SALT Parity reforms to date, with another half-dozen actively considering them. Those new laws have enabled pass-through businesses to save north of $10 billion each year, a figure that will only increase as more states and businesses embrace the approach.

As background, the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act subjected deductions on state and local taxes (SALT) on pass-through business income to the same $10,000 cap as other taxes by individuals. Taxes paid by the business entities, like C corporations, remained fully deductible.

The premise behind our SALT Parity approach is simple: If taxes paid by business entities remain deductible, then states should allow their pass-through businesses the option to pay their taxes at the entity level. Key components of a good SALT Parity bill include 1) an election to pay at the entity level; 2) a credit or income exclusion to protect owners from double taxation; and 3) recognition of the SALT taxes paid to other states. That’s it.

So the SALT Parity framework is pretty simple. The details, however, are not. Having worked directly with about two-dozen states on their reforms, our experience is that each state presents its own unique challenges and preferences. Which businesses can make the election? Do you use a credit or an exclusion? Do you recognize the SALT taxes paid to other states? What tax base should you use – a narrow, in-state income base or one that includes a businesses’ total income? When does the company make the election? When does it take effect?

To help get a better understanding of how the states answered these and other questions, we put together the following table comparing the various SALT Parity bills currently in place:

The table raises some important considerations for lawmakers in those states remaining to take action. (Pennsylvania, we’re looking at you here!)

For starters, only one state (Connecticut) chose to force businesses into the entity tax regime – the other 30 acting states allowed an election. Elections are clearly the preferred approach, as the benefits of SALT Parity vary based on each firm’s individual circumstances. The businesses hurt most by Connecticut’s mandatory approach are those residing in Connecticut.

Defining which businesses are eligible to make the election is another question. Some states exclude corporate shareholders and tiered ownership structures while others, including Kentucky, limit eligibility to businesses owned by natural persons. This latter limitation prevents many family businesses from making the election, as they often have ownership held in trust. As we communicated to Kentucky and others, there’s no real purpose served by these limitations and they should be discarded.

A key selling point of our efforts is that SALT Parity cuts taxes on businesses without reducing revenues to the state. It’s a win-win. For some states, however, that wasn’t good enough. Massachusetts, for example, capped the value of the credit at 90 percent. Connecticut initially allowed for a full credit, but subsequently reduced its value to 87.5 percent. It’s hard to see these provisions as anything other than a cash grab. They also undermine the core objective of SALT Parity: to put pass-through businesses and C corporations on an equal footing. As the Governor of Massachusetts argued in his veto statement (later overridden):

This bill… to implement an optional pass-through entity excise in the amount of the personal income taxes owed on members’ flow-through income and an accompanying tax credit equal to 90% of each member’s portion of the excise. It mirrors an outside section I filed in my initial budget recommendation, with one exception; in my proposal, 100% of the optional excise would be returned to the taxpayer.

[I]t is my opinion that taxpayers should be allowed to reap the full benefit of this policy, especially where struggling businesses are still emerging from the pandemic and state revenues are strong. My view on the fair way to execute this policy remains unchanged. For this reason, I am returning House Bill No. 4009 unsigned.

Our SALT Parity efforts have run into other challenges, with recent developments in California serving as a cautionary tale. The state placed a $5 million limit on tax credits claimed in 2021, including those generated under CA’s pass-through entity tax law. Businesses with annual tax liabilities exceeding $5 million will have to carry forward the excess credit amounts until 2026, when the state’s SALT Parity statute expires. In essence, these companies are providing California with an interest-free loan for the next three years. Couple that dynamic with California’s narrow eligibility requirements and you’re left with a SALT Parity law that is needlessly complicated and unnecessarily hinders the ability of the state’s businesses to benefit.

Finally, while the majority of states opted for permanent PTET regimes, a handful of states chose to sunset them in 2026 (California, Virginia), or keep them in place only while the federal SALT cap is on the books (Colorado, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Minnesota). The rationale is that if the federal SALT cap expires in 2026 or sooner, SALT Parity would no longer offer a benefit.

The problem with this argument is twofold. First, the SALT cap may not sunset as scheduled. There’s bipartisan support to extend the caps, either at their current levels or at some increased level. Second, it is just not true that the benefit expires with the cap. Lower-income business owners would continue to get both the federal standard deduction and the SALT deduction post-cap, while upper income business owners are more likely to get 100 percent of their SALT deducted as a business expense than as an itemized deduction on their individual taxes. Permanence is always the preferred approach, especially given that the PTET is an election.

The point here is not to criticize states for their approach in implementing our SALT Parity reforms. After all, this was uncharted territory just a few years ago and states should be lauded for taking up measures that help their pass-through business community. Rather, our goal is to highlight what makes an effective PTET regime based on the experience of the acting states.

We hope this message reaches lawmakers in the states that have yet to enact SALT Parity. As always, we are ready to assist in any way we can. With billions of dollars at stake, there’s no reason for states like Pennsylvania, North Dakota, and Maine to remain on the sidelines.