Just in time for tomorrow’s Senate Budget Hearing, a new NBER Working Paper – coauthored by Gabriel Zucman and entitled, “Tax Evasion at the Top of the Income Distribution: Theory and Evidence” – was released this week, with the headline-grabbing conclusion that rich people significantly underreport their income.

This paper is in the same vein as the other work put forward by Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (PSZ), coupling headline-grabbing conclusions with highly dubious assumptions. PSZ got rich selling the idea that the rich have gobbled up all the economic gains in recent years, but their academic reputations are in tatters. Here’s a short list of papers in recent years correcting their previous work:

- “Income Inequality in the United States: Using Tax Data to Measure Long-Term Trends” – Auten and Splinter

- “Business Income at the Top” – Wojciech Kopczuk and Eric Zwick

- “The Big Fib about the Rich and Taxes” – AIER

- “U.S. Taxes are Progressive: Comment on “Progressive Wealth Taxation” – David Splinter

- “Reply: Trends in US Income and Wealth Inequality: Revising After the Revisionists”

David Splinter - “Who pays more taxes” – The Grumpy Economist

If you can’t absorb all this in the next few hours, the Larry Summers take-down of Saez in 2019 pretty much sums it up. At the end, Saez merely shrugs and says, “maybe we got our numbers wrong.” You think?

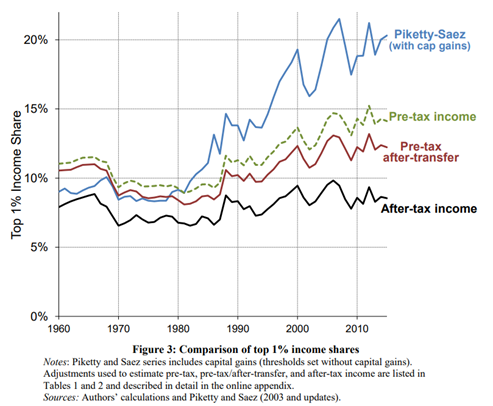

Or just absorb this table, showing that corrections to PSZ errors completely undermine their narrative on increasing income shares at the top.

Despite this dubious history, the new study has been touted as showing the “top 1% of households fail to report about 21% of their income.” Here are the key paragraphs from the paper:

In our preferred estimates, the top 1% income share rises from 20.3% before audit to 21.8% on average over 2006–2013. The result that accounting for tax evasion increases inequality is robust to a wide range of robustness tests and sensitivity analysis (for instance, it is robust to assuming zero offshore tax evasion).

We estimate that 36% of federal income taxes unpaid are owed by the top 1% and that collecting all unpaid federal income tax from this group would increase federal revenues by about $175 billion annually.

As standard audit procedures can be limited in their ability to detect some forms of evasion by high-income taxpayers, additional tools should also be mobilized to effectively combat high-income tax evasion. These tools include facilitating whistle-blowing that can uncover sophisticated evasion (which helped the United States start to make progress on detection of offshore wealth) and specialized audit strategies like those pursued by the IRS’s Global High Wealth program and other specialized enforcement programs.

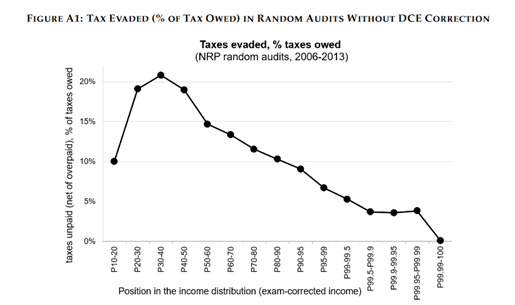

There is a certain “man bites dog” aspect to these conclusions, as tax evasion is a heavily studied topic and the IRS has engaged in numerous efforts to better quantify the source and amount of the evasion. This table, from the IRS’s National Research Project, represents the conventional view of the where evasion lies:

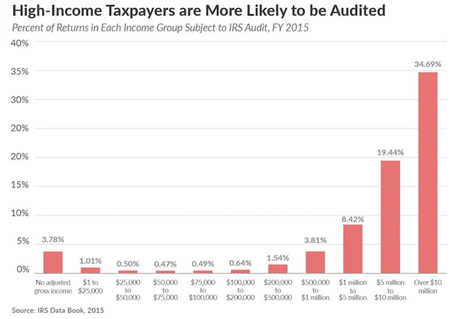

Notice how the incidence of evasion declines with income? That’s because the checks and balances in the tax code increase as income increases, including increased audits. Contrary to popular opinion, taxpayers in the highest income classes can expect to be audited regularly, as this chart shows.

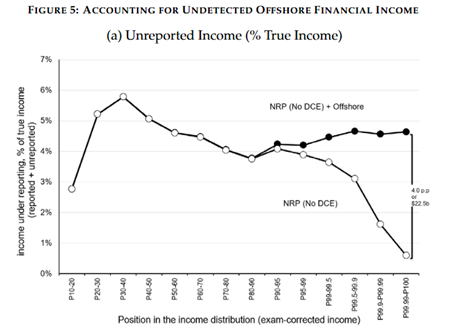

But the Zucman et al. paper claims that these audits are ineffective at finding off-shore accounts, and that these off-shore accounts are hiding an enormous ($1 trillion) amount of undeclared income. This results in their claim that the rich hide a much higher percentage of their income than previously thought.

Evidence for this claim comes from two sources: participants in the Offshore Voluntary Disclosure Program (50,020 taxpayers), and first-time filers of the Foreign Bank Account Report (31,7752 taxpayers). Couple problems with this approach.

First, as Zucman et al. readily admit, these are hardly representative populations. The OVDP was a tax amnesty program beginning in 2008 for people with undisclosed off-shore accounts, while the paper also focuses on first-time FBAR filers from 2009 to 2011. Not exactly a random sample.

Second, these programs are already in place, and those 80,000-plus taxpayers are presumably now in compliance. They are reporting their accounts and paying taxes on their overseas income. There are only 120,000 or so taxpayers in the top 0.1 percent. Sounds like they got them.

Finally, look at the Unreported Income table. The adjustments for hidden overseas income begin with the top 20 percent of taxpayers. This seems remarkable, as you can make it into the top 20 percent with about $200,000 in pre-tax income. Do Zucman et al. really believe a large percentage of taxpayers making upper-middle class wages are sheltering income in Swiss bank accounts?

Will the assumptions made in Zucman et al. prove correct? Maybe, but history suggests it’s not likely. Moreover, with the paper coming out one day, the hearing scheduled for a couple days later (Zucman will testify tomorrow), and these issues front and center before Congress this summer, there simply won’t be time to correct the record before Congress votes.

Where does that leave us? We’re guessing the shelf life of this study is about 18 months. That’s how long it will take for the economics world to pull the data and correct the record. As Scott Winship observed on Twitter the other day, PSZ really have just one play in their playbook:

New research from P, S, or Z on inequality or taxes is like the starting point of a negotiation. Initial offer is high, based on one-way biases, but researchers assume that. Better research tempers it once the media coverage subsides. But initial offer is what everyone remembers.

Pretty much sums it all up.