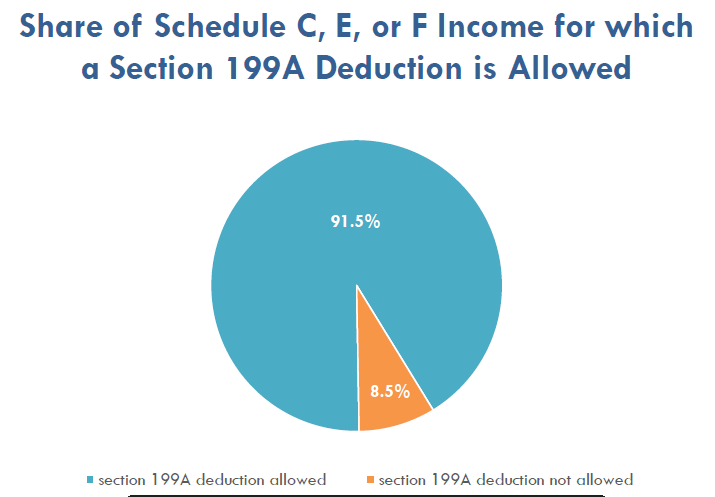

Remember this JCT chart from earlier this year? It garnered lots of attention and called into question how the 199A pass-through deduction was structured. If only 9 percent of all pass-through income was disqualified from getting the deduction, what was the point of having all those complicated rules?

We wondered about the estimate at the time, as it didn’t comport with our member’s experience. In our S-CORP survey this year, only half of our members expected to get the full deduction, while rest expected just a partial deduction or no deduction at all. How was it possible the excluded income of all those firms is only 9 percent of the total?

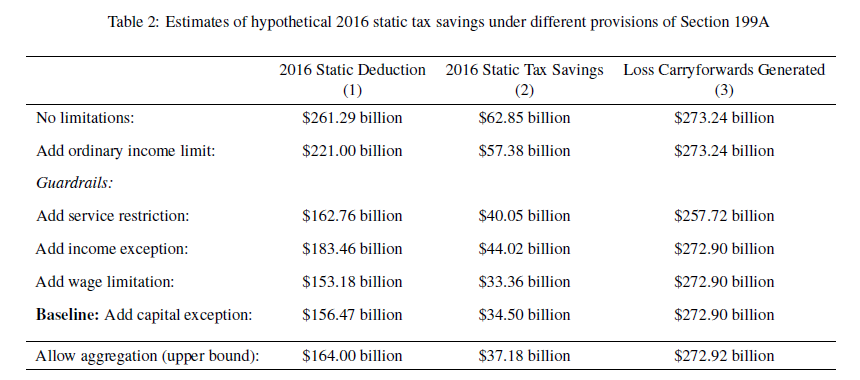

A Treasury paper from May suggests that our members might be right. According to Treasury, the amount of pass-through income disqualified by the Section 199A limitations could be 40 percent, not 9 percent. While Treasury makes clear the mechanics of their estimate differs from the JCT’s, that’s still a big difference. Somebody is off by a factor of four! Here’s the table from the Treasury report:

As you can see, far from having little impact, the limitations significantly reduce the amount of income eligible for the deduction, particularly the exclusion of specified services businesses and wage guardrail.

Why is this important? Lots of reasons. First, it makes a difference on revenue estimates and parity. Here’s Treasury on their estimate and the Joint Committee’s:

Our baseline estimate, reported in the sixth row of Table 2, is that taxpayers would have claimed $156 billion in deductions in the absence of behavioral responses, yielding total tax savings of $34.5 billion. These estimates are adjusted for inflation to 2018 dollars, as are all dollar values in this section, unless otherwise indicated. For comparison, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the 2019 fiscal year cost (which includes portions of the 2018 and 2019 tax year costs) of the 199A deduction is $47.1 billion (Joint Committee on Taxation, 2017; not adjusted for inflation). The Joint Committee’s 2018 fiscal year estimate of $27.7 billion is also informative. It includes only a portion of the 2018 tax year cost and therefore places a lower bound on the 2018 revenue effect (Joint Committee on Taxation, 2017). We note that the Joint Committee’s estimates include forecasts of behavioral responses to the deduction, which tend to increase its cost, and their estimates include a richer interaction with other TCJA changes. Furthermore, their estimates include the effects of the Section199A deductions for qualified Real Estate Investment Trust dividends, qualified publicly traded partnership income, and certain income from co-operatives; our estimate does not.

Different methods might explain some of the gap between $34 billion and $47 billion, but not all. If Treasury is right about the Section 199A guardrails, then the JCT significantly overestimated the value of the Section 199A deduction to pass-through businesses.

Meanwhile, it looks like the JCT vastly underestimated the corporate tax relief in the TCJA. The JCT initially predicted corporate revenues would be $243 billion in 2018. Despite rising earnings, actual revenues were just $205 billion and they are tracking at similar levels for 2019. In the balancing act between corporate and pass-through tax treatment, there is growing evidence the JCT’s tax reform estimates were tilted against the pass-through sector.

Second, since the disqualification of specified services business income and other guardrails only apply to business owners with incomes exceeding $315,000, underestimating their effectiveness will greatly impact the JCT’s distribution tables. The media had a field day with the JCT estimate that two-thirds of the Section 199A benefit goes to taxpayers over the income threshold. The Treasury analysis suggests that estimate is too high.

Finally, contrary to the implication that the Section 199A’s guardrails are ineffective, the reality on the ground is that they have real teeth, particularly the wage guardrail. It’s difficult to fake W-2s and wages paid are a reasonable, easily measured proxy for other factors that make up a real business. That’s why the wage guardrail was proposed by our business coalition in the run-up to tax reform. There’s a certain populist attraction to it too – if you want the deduction, create some jobs.

Some corporate CEOs recently floated the idea that they should focus more on jobs and less on profits. It’s a worthy sentiment, but their actual statements lacked any real substance. It’s one thing to say you’re going to focus more on job creation, it’s another to do it. The wage limitation on the pass-through deduction, on the other hand, is real. For business owners above the threshold, the surest way to get the pass-through deduction is to go out and create some jobs. Maybe those corporate CEOs would support applying the wage guardrail to the 21-percent corporate rate too? That would be consistent with their recent press, but we’re not holding our breath.