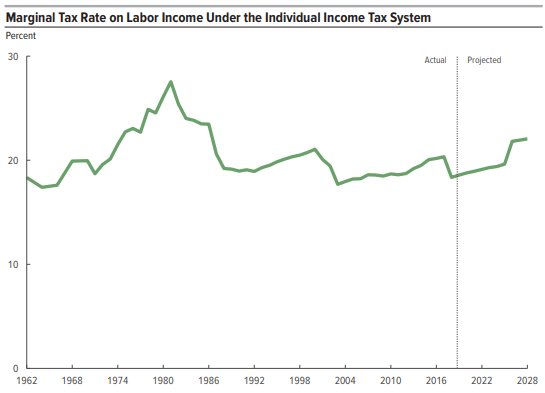

Earlier this year, the Congressional Budget Office produced a report reviewing tax rates on labor income since 1962 that includes some important lessons for tax policy folks.

The first lesson is that nothing replaces a really cool chart. Take this heat map, for example. What a great way to convey a lot of information all at once. If you’re a taxpayer, the simple way to view it is lighter colors good, darker colors baaad.

Our second lesson is how much more progressive the tax code has become since the 1960s. Back then, nearly everybody paid statutory rates between 16 and 28 percent. Today, those rates are limited to the top quarter of taxpayers. Around three-quarters pay lower rates ranging between 0 and 15 percent. This vast improvement in how we tax the middle class is completely lost in today’s political discourse.

A third lesson is the dramatic impact inflation had on tax burdens. See how thin those dark lines are prior to 1970? Marginal rates were really high back then, but few taxpayers paid them and they didn’t raise a lot of revenue. Then came the high-inflation 1970s. As the CBO notes:

Throughout the 1960s, fewer than 0.5 percent of tax filers faced a statutory rate of 50 percent or more, and the number of tax filers facing rates higher than 28 percent fluctuated between 2 percent and 4 percent. In the 1970s, the share of tax filers in high rate brackets began to grow rapidly. By 1981, 1.5 percent of returns fell into tax brackets with tax rates of 50 percent and higher, and almost one-quarter fell into brackets with rates higher than 28 percent. The rapid increase occurred despite stability in the tax law because the tax system was not indexed for inflation and rapid inflation in the 1970s pushed many taxpayers up the rate schedule.

We hear lots lately about how high top tax rates were in the 1950s and 1960s (91 percent) and how those high rates didn’t seem to hurt the economy, but this chart puts the lie to those claims. It’s hard for high rates to hurt the economy when nobody pays them. It was only when inflation pushed increasing numbers of taxpayers into the upper brackets that they began to have any relevance. Apparently, taxpayers can plan around high rates, but they can’t plan around inflation.

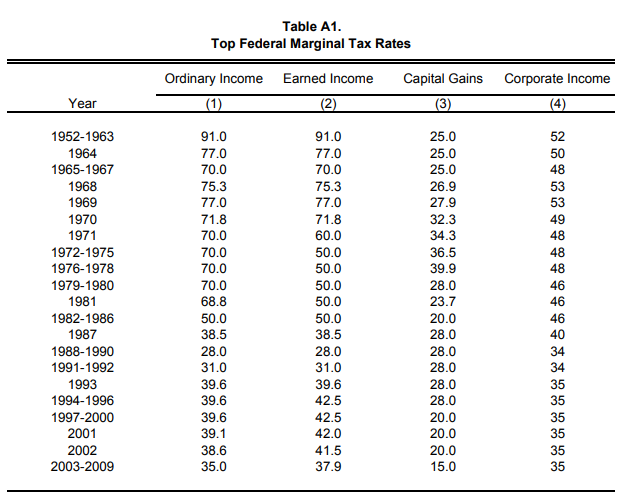

How exactly did high income taxpayers avoid the ridiculously high rates of the 50s and 60s? In many cases, they paid taxes (if they paid taxes at all) using other rates. This table from a 2009 paper by economists Slemrod, Saez and Giertz shows the top tax rates for different forms of income dating back to 1952. As you can see, taxpayers back then had a choice to pay marginal rates of 91 percent on their wage and salary income, 52 percent on their corporate income, or 25 percent on their capital gains income. The paper’s key finding is that recognizing earnings shifted from one form of income to another is a key to accurately measuring taxpayer responses to rate changes.

Using corporations as tax avoidance vehicles was a popular choice back then, and it stayed popular right up until the 1986 Tax Reform Act. The pre-86 corporate rates were lower and the deduction opportunities bigger. With the new rate structure and greater deduction opportunities for corporations under the TCJA, it’s likely to be popular again real soon.

Our final observation is how consistent actual tax burdens are. Top tax rates varied wildly in the past sixty years, but the above chart shows the average rate has been remarkably solid at around 20 percent throughout it all. It spiked with inflation in the late 1970s, and it rises a few points with each market bubble, but that’s about it. And, as we noted above, this steadiness occurred over a time when top tax rates were cut in half and the tax code became more progressive.

So what is the overall lesson? The report demonstrates that really high tax rates don’t work as advertised. Taxpayers actively avoid them, so they leak revenue, distort behavior, and hurt the economy. When inflation in the 1970s surprised taxpayers and forced a meaningful number of them into those high rates, the economy suffered. Remember President Carter’s “Malaise” speech? We weren’t suffering from a “crisis of confidence”, we were suffering from a massive, inflation-caused tax hike. Taxpayers revolted, Reagan got elected, and rates came down (and were indexed for inflation too).