Massive deficits, the fiscal cliff, and Social Security’s pending insolvency are jump-starting a long overdue debate over real tax reform – specifically, how should we best reorganize the tax code to survive the fiscal hurdles we know are coming?

Three distinct voices have emerged recently to offer their views. Which offers the best hope for success? What impact would each have on small and family-owned businesses? Here’s a review of the competing plans, together with some thoughts on how to best tax business income from the Main Street perspective. (In a follow-up post, we will put forward our own plan for tax reform.)

The Estonian Example

The Tax Foundation is a big fan of the Estonian approach to taxation, and for good reason. Estonia combines a simple, flat income tax for individuals with a distributed profits tax for businesses, resulting in a single tax system where everything is taxed just once and at the same reasonable top rate.

According to the Tax Foundation, a similar approach applied in the United State would result in a larger economy, more jobs, and higher wages. Key features of the US plan include:

- A flat, 20-percent tax on individual incomes, including capital gains;

- A refundable, $2,000 Child Tax Credit, current EITC, and increased standard deduction and personal exemption;

- A 20-percent tax on distributed business profits coupled with an exemption for the subsequent dividends at the individual level; and

- The elimination of the estate tax and NIIT.

Economic benefits aside, the beauty of a single tax system is its simplicity. So much of the tax code’s compliance and enforcement costs stem from determining which rates apply to what income, so imposing a single top rate on all forms of income would eliminate all that complexity.

Another source of simplicity would be the plan’s elimination of multiple taxes. If a tax regime is a unique rate coupled with a unique base, then the US subjects taxpayers to at least seven – individual taxes, wage taxes, the corporate tax, the NIIT, estate taxes, capital gains taxes, and the AMT. The Estonian approach would eliminate four of these and should allow Congress to repeal more than half the income tax code.

One challenge with the Estonian plan is it would lose revenue. The write-up says: “At the end of the budget window, the plan loses about $100 billion in 2033 on a conventional basis.” They do argue economic feedback would result in higher revenues, but that depends on strong returns to the expensing and corporate tax relief, estimates that are iffy at best. Remember how much feedback the 21-percent corporate rate was supposed to generate?

Another problem is the distributed profits tax, where business income is taxed only when it is distributed to the owners. This type of levy might make sense in a small, capital starved country like Estonia, but in the US it’s an invitation for tax evasion. We already have a problem with hoarding at the 21-percent corporate rate. Imagine the tax avoidance that would accompany a zero-percent rate?

Finally, the plan would exempt foreign investment from the tax, “so long as it is subject to corporate tax in its foreign location.” Again, this might work in tiny Estonia. In the world’s most attractive investment destination, it’s a recipe to steal.

It’s Backkkkkk! The 15-Percent Corporate Rate

We could do real tax reform, or we could just cut the corporate rate again. That appears to be the message from Tax Foundation’s Garrett Watson, who published a piece promoting the Trump policy just last week. Garrett argues:

The current corporate tax rate leaves room for more progress to enhance U.S. competitiveness. Reducing it to 15 percent would bring the combined U.S. rate down to 20.1 percent, just above Estonia’s combined rate of 20 percent. In the OECD, only Hungary, Ireland, and Luxembourg would have a combined corporate tax rate significantly lower than the U.S. Enhanced international competitiveness will make the U.S. a more attractive location for business investment, raising economic opportunities for American households and reducing incentives for businesses to move operations overseas.

This obsession with the corporate rate is silly and flies in the face of the Estonian approach above. One plan imposes the same top rate on everybody, the other creates a huge, unsustainable imbalance between corporate tax treatment and everybody else. Garrett recognizes the inherent problem, writing:

A 15 percent corporate rate would improve U.S. competitiveness and grow the U.S. economy. However, policymakers and candidates should pair tax rate changes with tax base reforms to ensure the cost of tax cuts is paid for, investment is not penalized, and broader tax reform is not left off the table.

A nice sentiment, but as “Bert and I” once observed, you can’t get there from here. A 15-percent corporate rate reduces revenues by $750 billion or so. Offsetting those revenues with base broadening sounds great, but we just did that and, unlike the individual and pass-through provisions, those changes are permanent. To offset additional corporate cuts, Garrett would need to raise taxes on individuals and Main Street businesses. Again.

How would Main Street fare under a 15-percent corporate rate? For larger pass-through businesses, the response would be simple – they would convert. No more large S corporations, no more large partnerships.

That might make the JCT happy, but it’s not going to improve the economy. Why? Because public companies have a huge advantage over private companies when everybody is a C corp. They have access to the capital markets, their shareholders buy and sell their stock without transaction costs, and three-quarters of their shareholders pay no taxes or greatly reduced taxes, so the double tax doesn’t apply to them.

S corp shareholders are all taxable, on the other hand, so the double tax hits them hard. Plus, S corps have to pay dividends. How else do you reward owners of a private company? Over time, the public company advantage simply overwhelms the family business sector. It would be pre-1986 all over again.

Bottom Line: Giving companies that already pay the lowest rates another tax cut might provide a windfall to Apple and Amazon, but the cost would fall on individuals and pass-through businesses and further the economic consolidation that’s been taking place in recent decades. That might be good for Wall Street, but it’s bad for Main Street and the people who live there.

Deese & Kamin on Tax Reform

Finally, , former Biden NEC staffers Brian Deese and David Kamin penned a recent Tax Notes article arguing that the tax policy response to our fiscal challenges should conform to the following five principles:

- at a minimum, fully pay for tax reform relative to current law and strengthen the tax base to facilitate future increases in revenue;

- focus the existing limited fiscal space on helping lower-income families;

- reverse the erosion of the corporate income tax system while maintaining incentives to innovate and invest;

- eliminate tax cuts for the highest-income Americans and increase their contributions relative to the pre-2017 tax system; and

- improve tax administration and simplify tax filing.

First, these don’t look much like principles. They look like goals. The authors may think the rich should pay “more” but that’s hardly a governing principle, is it? More compared to what? When exactly do we reach “more”?

Anyway, Deese and Kamin are calling for tax reform that is deficit neutral, raises taxes on corporations and the rich, reduces taxes for lower-income families, increases funding for the IRS, and sets the stage for future tax hikes. In other words, the basic tax playbook of the Biden administration.

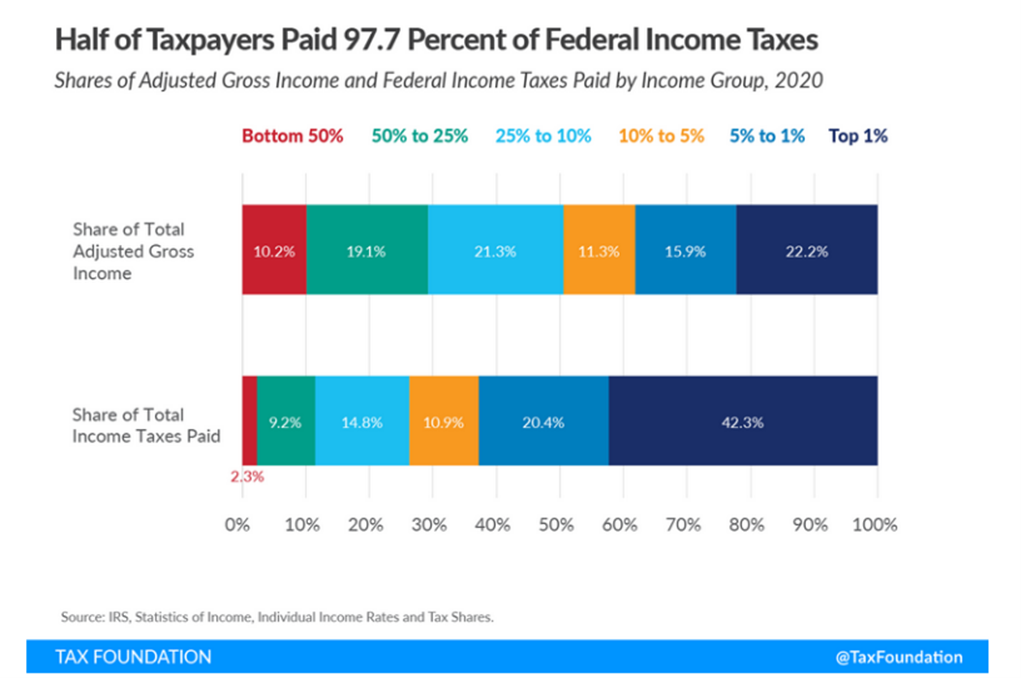

Couple problems. First, reducing taxes on lower-income families sounds good, but the combo platter of the EITC, Child Tax Credit, and larger standard deduction means that most low and modest income families don’t pay income taxes. Here’s the Tax Foundation on income tax distribution in 2020:

See how the bottom 50 percent of taxpayers only paid 2.3 percent of all income taxes? It’s actually less, as the percentages exclude the refundable portion of the family tax credits. As a result, calls for reducing their taxes really means sending bigger checks. You may support that, but it’s not tax reform.

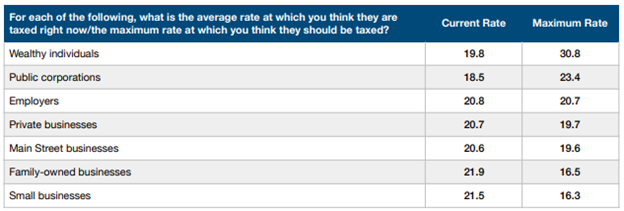

Second, raising taxes on the wealthy may poll well, but only when the poll’s respondents fail to understand how much the rich already pay. As our surveys from the Winston Group demonstrate, wealthy taxpayers and private businesses already pay rates well above what most Americans think is fair.

Finally, the dirty little secret of the TCJA is that its tax relief went mostly to C corporations and lower-income families, not wealthy taxpayers. That might surprise Tax Notes readers, as Deese and Kamin include detailed tables showing who got what. The problem is they use Brookings estimates that ignore actual tax payments and focus instead on “post-tax income.”

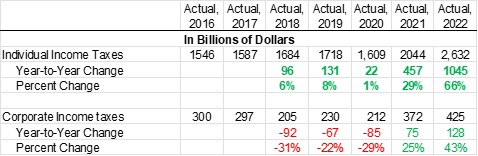

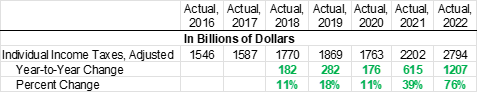

Here are the actual revenue collections from the Congressional Budget Office. As you can see, collections on corporations dropped sharply post 2017, while individual collections went up.

Moreover, the individual collections reflect tax relief targeted at low-income families, including a larger standard deduction and a larger child tax credit. Those two TCJA provisions reduced individual income taxes by $1.3 trillion (yes, $1.3 trillion) over ten years. Add that back in and the remaining tax base of higher-income taxpayers and pass-through business owners paid $182 billion more in 2018 than they did in 2017, an 11-percent increase. Some tax cut.

How does the Brookings data show tax cuts for the wealthy when their payments went up? Their “Expanded Cash Income” data includes both corporate income and corporate tax relief. So while many pass-through business owners saw their taxes go up post-TCJA, Brookings has them going down by apportioning the large corporate tax cuts to them. Kind of like rubbing salt in the wound, no?

Exactly whose taxes went up post-TCJA? It’s a mixed bag. Do you reside in a high tax state? Do you get the 199A deduction? Did you lose the 199 manufacturing deduction? Do you have excess losses, high interest expenses, or large R&E costs? Generally, a pass-through business operating in high tax states but excluded from 199A got killed. A 199A-qualified business operating in no-income tax states did just fine.

Another problem. Deese/Kamin resurrect the old trope about the erosion of the corporate tax base. They write that “[o]ver the decades, federal corporate income tax receipts have fallen considerably as a share of the economy — even as that has not been true of corporate profits.” But the data they use to measure profits includes S corporations, while their data on tax payments does not. This paper from the BEA explains the issue. The corporate tax base didn’t erode — it migrated to the pass-through sector where, you may have noticed, they pay higher rates these days.

Finally, missing from Deese/Kamin is any discussion of jobs or economic growth. The only reference to jobs is in the title when they cite the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, and the only reference to economic growth is when they discuss the challenge of higher interest rates paid on our national debt. This lapse continues a disturbing trend of tax policy experts simply ignoring the effect tax policy has on the economy, focusing solely instead on who pays what.

Bottom Line: Deese and Kamin may argue tax reform should make the wealthy pay more, but they can’t argue that this would be a change from recent policy. The TCJA already did that.

Conclusion

S-Corp put away its crystal ball following the 2016 elections, but you don’t need a clairvoyant to know Congress is going to debate a very large tax bill at the end of 2025 and everything will be on the table when Social Security goes broke in ten years. Here’s the Tax Foundation:

[D]ue to the TCJA, much of the individual income tax code is set to expire after the end of 2025, while several business tax increases have already begun to take effect, including the phasedown of bonus depreciation beginning this year, making now an opportune time to consider fundamental tax reform. The weakening economy, high interest rates and inflation, and severe fiscal challenges ahead also make fundamental and pro-growth tax reform more important than ever.

That last phrase is the key – how do you reform the tax code to raise the revenues the government needs while encouraging robust economic growth? It won’t be easy, but we have some ideas.

Next Up: A Tax Reform Plan for Main Street