Word on the street is that House Republicans will put together a package of pro-growth provisions later this Spring, including a tax title. The effort is timely given our uncertain economic outlook and the current tax landscape, and it works especially as a counter to the Biden administration’s aggressively anti-Main Street budget proposals.

What might make it into the tax package? Here are some suggestions.

Inflation, EBIT, and 163(j)

A big revenue raiser in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was the new cap on interest deductibility. Starting in 2018, the amount of interest expense a business could write off was limited to 30 percent of its earnings before interest, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA). As of January 2022, that cap applies just to EBIT, a much more stringent limitation. The provision raised $250 billion over ten years and was designed to complement the TCJA’s expensing provisions.

The pro-cyclical nature of the interest cap, however, means businesses get hit especially hard as economic conditions worsen, as any decline in revenue necessarily reduces the amount of interest that can be deducted. In her recent piece in Forbes, Lynn Mucenski-Keck, an S-CORP Advisor and Partner at Withum, gives an example of how this can play out:

Assume a taxpayer has preliminary taxable income of $300,000 during the taxable year, including $200,000 of business interest expense, and depreciation of $500,000. Before the change in the depreciation, amortization, and depletion addback for the 2022 taxable year, the full amount of business interest expenses would have been an allowable deduction. However, as depreciation can no longer be added back as of 2022, the allowable business interest expense deduction will only be $150,000, or 75% of the overall business interest expense incurred. The disallowed business interest expense can be carried forward indefinitely, but generally cannot be utilized unless the entity creates excess taxable income or income above what is needed for the current year’s business interest expense to be absorbed.

This dynamic was always of concern, but now with today’s much higher interest rates, Section 163(j) amounts to a backdoor tax hike that will force companies to significantly cut back on their capital expenditures.

There’s a Main Street angle to this as well. Publicly-traded companies have access to capital markets for both debt and equity infusions, so their cost of capital is typically lower than that of private companies. All things being equal, then, one would expect a private company to be more affected by the cap than their public competitors.

Recommendation: The interest deduction cap takes an already-uneven playing field and makes it even worse for Main Street. Congress should restore the EBITDA base for the cap.

R&D Expensing

Another TCJA policy change ($120 billion) was the requirement that companies amortize their research and experimentation expenses over five years, rather than write them off immediately. The stricter rules went into effect at the start of 2022 and, despite repeated rumors of legislative relief, none has materialized.

Here’s Lynn again in a separate article explaining the real-world impacts of the policy:

The partisan Congressional divide will likely force businesses to reduce 2022 Section 174 R&E deductions to as little as 10% for domestic and 3.3% for foreign research. Such a significant decrease in deductible expense is staggering compared to other countries, including China which provides a deduction 20 times higher than the U.S., or a 200% deduction, for R&E expenditures.

The complex nature of the provision also means that smaller firms that lack the resources of their larger counterparts will struggle to comply with the change:

Unfortunately, a significant amount of information must be digested for Section 174 R&E capitalization. There is limited guidance and the rules oftentimes do not follow the same logic as the research credit. To say taxpayers are frustrated with the requirement to capitalize Section 174 R&E is an understatement. After all, isn’t the U.S. viewed as the land of innovation? But now innovative businesses in the U.S. are feeling penalized in comparison to their counterparts overseas. And even when businesses are trying to comply, the lack of guidance surrounding the requirement can be overwhelming.

Recommendation: Scrapping the amortization requirement would eliminate the need for better guidance, and would restore an incentive for companies to invest in R&E – an incentive that had been part of the Tax Code for literally decades.

Loss Limitation Rules

Section 461(l) of the TCJA caps the losses a pass-through business owner can use to offset other forms of income. This provision is essentially a timing difference – losses not deducted this year are available to be deducted next year – yet the provision was scored as raising 160 billion, or about 40 percent of the revenue loss from the 199A deduction.

This massive (and unwarranted?) score has turned Section 461(l) from a sleepy revenue raiser into a veritable political football. That’s unfortunate, because we really are discussing just a timing difference here – as in when the deductions can be deployed – which will take on increased significance in the next economic downturn.

As to the policy, prior to the TCJA, pass-through owners were able to take active business losses – losses from businesses an owner actively runs – and use them to offset other forms of income. Under the TCJA, this ability was capped at $500,000. Any excess losses are carried over into the next year and treated as Net Operating Losses (NOLs).

The cap was originally scheduled to sunset in 2026 along with the rest of the TCJA’s individual provisions, but in recent years lawmakers, capitalizing on wildly inflated JCT scores, have extended the limitation twice – first as part of the American Rescue Plan then as an amendment to the Inflation Reduction Act – so the limitation is now in effect through 2028.

As noted above, the loss limitation rules originally served as a partial offset for the Section 199A deduction. But with their successive extensions, they have effectively been treated as a piggy bank for new congressional spending.

There are two problems with this. First, these revenue scores need to be reexamined. If we are correct that they are wildly overinflated, then the revenues aren’t real and the new spending that accompanies them is simply adding to the deficit.

Second, as with the interest deductibility cap, this is a timing issue that hurts companies when the economy is weak and business losses increase. It forces them to take losses that could be used to reduce taxes when times are tough and pushes them into the future when the economy (and business profits) have recovered. It is procyclical and bad tax policy.

Recommendation: Repeal Section 461(l).

199A Permanence

In addition to targeting past tax hikes, the House should consider making 199A permanent as part of their package. Under current law, the 199A deduction sunsets at the end of 2025 creating a scenario where smaller, family-owned companies will be paying marginal tax rates more than 12-percentage points more than their public company competition. Such a disparity is simply unsustainable and will exacerbate the trend towards consolation of economic activity already happening in the country.

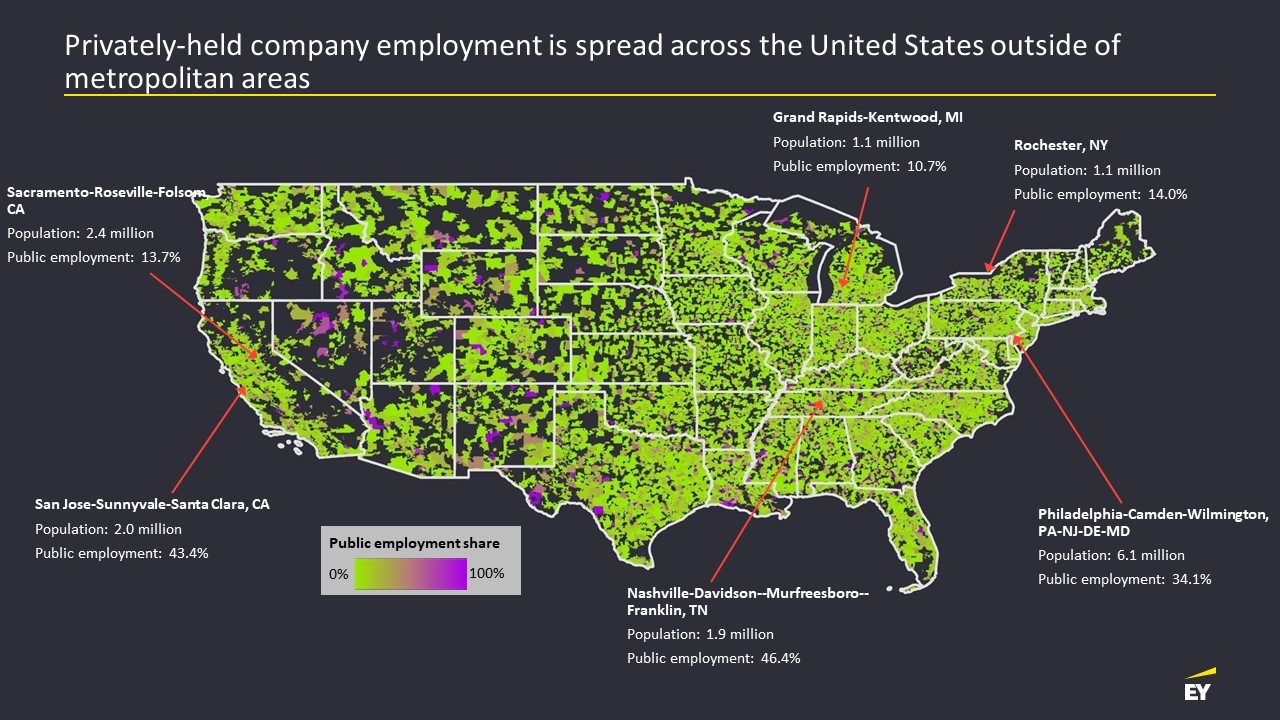

This dynamic has geographical as well as business-type implications. Privately-owned companies and their employment is more evenly spread across the country, so tax policies that disadvantage small and family-owned businesses will have a disproportionate impact on certain regions over others.

199A helps balance the tax treatment of family businesses with the treatment of public companies. But it expires in two years, while the 21-percent corporate rate is permanent.

Recommendation: Congress should move proactively to make 199A permanent and give Main Street employers the certainty they deserve.

Conclusion

After three years of COVID, shutdowns, supply chain disruptions, and inflation, the House is right to seek something positive that helps employers and families. Instead of seeking ever higher taxes from the pass-through business sector, lawmakers should work to make the small and family-owned business deduction permanent and address these other challenges that confront them. We look forward to working with the House and the Senate to promote these ideas.