At a hearing last week, Finance Chair Ron Wyden stated:

More than two out of every three dollars earned by partnerships in this country go to the top one percent of earners. These are sophisticated entities that bring in big revenue. However, the most recent data shows that out of millions of partnership returns filed in 2018, only 140 were audited. If you’re a wealthy tax cheat in a partnership, your odds of getting audited are slightly higher than your odds of getting hit by a meteorite. It’s an audit rate of 0.00004 percent. On the other hand, taxpayers who claim the EITC are much, much likelier to get audited. Again, something is out of whack when it comes to enforcement.

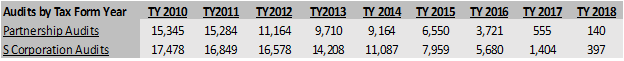

The Chairman’s audit statistic comes from Table 17a of the 2019 IRS Data Book and it does show that for 2018 tax returns, only 140 partnership examinations have been initiated out of four million. S corporations appear to get favorable treatment as well, with only 397 examinations initiated out of nearly five million returns.

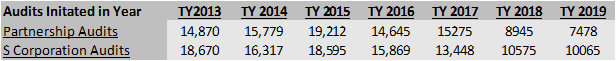

Sounds bad…but wait. Table 17b in the Data Book says that in FY2019, the IRS initiated 7,478 examinations of partnership returns and 10,065 examinations of S corporation returns. Those numbers are different. What gives?

What gives is that Wyden’s statistic refers to audits of partnership returns filed for tax year 2018 only. That means tax returns that were filed less than one year before the 2019 Data Book was published. There simply has not enough been time for returns from tax year 2018 to be examined, as is demonstrated by the rest of the table. Prior year data from table 17a shows how the number of audits for returns from any particular tax year grows over time.

Part of the challenge here is that table 17a is new to the IRS Data Book. Previous Data Books did not attempt to break down audits by filing year, and the new approach is confusing people. The authors recognized this challenge and provided the following warning:

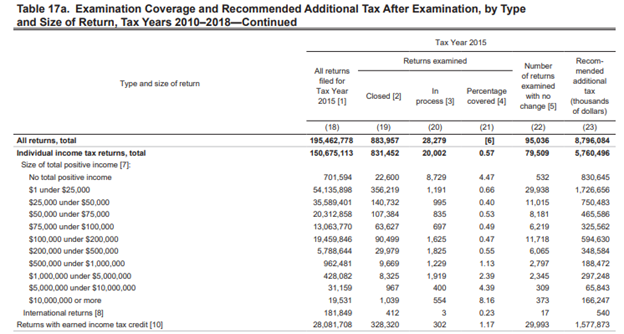

This table is presented as a “snapshot” in time, and the data will continue to change as open examinations close and new ones are opened. The number of audits for returns in recent tax years may appear low because, as of the end of FY 2019, relatively few examinations had been opened or closed. This reflects the normal timing of the audit process, which is based on when returns are identified and the applicable statutes of limitation. As new audits of returns filed for recent tax years are opened, audit rates for those years will increase. In contrast, audit rates are less subject to change for returns filed for tax years that are past the normal statute of limitations for assessment, which is generally 3 years for a return that had been filed timely. Tax Year 2015 is the most recent year outside the normal statute period. [Emphasis added]

So using table 17a with its focus on audits per tax filing year is not a good measure of how likely a partnership or S corporation is to be audited. It’s just too soon. Looking at audits initiated per fiscal year is better, and shows more robust enforcement:

But even this approach does not paint the entire picture, as it excludes audits of individual partners and S corporation shareholders. As the Chairman says, “More than two out of every three dollars earned by partnerships in this country go to the top one percent of earners.” How likely are the top one percent to get audited? Pretty likely, as it turns out.

Table 17a also breaks down audits of individual returns by income levels. We are using 2015 since, as the IRS notes, the statute of limitations has expired for that year and these data are likely to be final. To be in the top one percent in 2015, a family needed to earn $1.4 million or more. As you can see from the table, those families had about a 3 percent chance of being audit that year. Over a decade, that is nearly a one-third chance. Try telling taxpayers that a one in three chance of getting audited by the IRS in the next decade is “low.”

So table 17a in the 2019 IRS Data Book is new and sowing confusion. The audit rate of partners in this country isn’t 0.00004 percent and the audit rate for high-income partners is certainly higher than the audit rate for EITC recipients. Congress will have to decide how much funding the IRS needs, and how many audits are appropriate, but it should do so using real statistics that are correctly understood.