More evidence the campaign to target high-income taxpayers with more audits isn’t going too well. A new report by the Inspector General for Tax Administration at the Treasury Department (TIGTA) suggests the expanded audits are failing to raise the promised revenue. Here’s the WSJ’s take:

Unlike bank robbers, IRS auditors tend to look where the money isn’t. That’s what happened after the agency started scrutinizing more tax returns from the wealthiest Americans. A new report says increased targeting of these taxpayers was hugely ineffective.

The policy, launched in 2020 by former Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, required the IRS to audit 8% of taxpayers each year who earned more than $10 million. To hit that quota, the agency started examining returns with fewer irregularities. The efficiency drop was steep, according to the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, or Tigta, which recently reviewed the results.

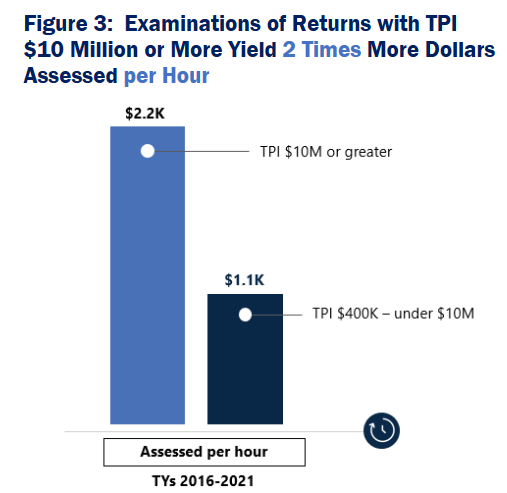

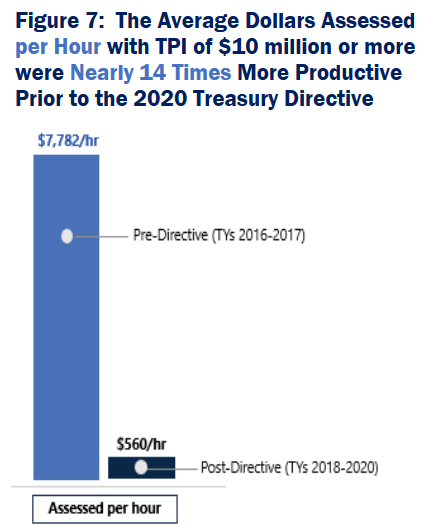

The average dollars assessed per return above $10 million “was nearly six times more productive prior to the 2020 Treasury Directive,” meaning the average examination recovered six times as much in unpaid taxes. Or to put it in terms of IRS productivity, after the policy change the money that auditors assessed per hour from this income group dropped 93%.

Reading the report provides a more nuanced picture. For example, this table appears to show that the audits are providing a positive return for the IRS:

The problem with these numbers is they ignore any audits that resulted in taxpayer refunds, plus they measure preliminary assessments only, not ultimate collections. These are not small considerations. For example, last year’s GAO report on the IRS’s new audit regime for large partnerships found the refunds actually exceeded the assessments:

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audits few large partnerships—54 in tax year 2019—and the audit rate has declined since 2007. More than 80 percent of the audits resulted in no change to the return on average from tax years 2010 to 2018, double the rate of large corporate audits. For those that did change, the average adjustment was negative $264,000. IRS officials attributed the declining audit rate to resource constraints. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) provided IRS with $45.6 billion for enforcement activities through the end of fiscal year 2031, and in response IRS identified large partnerships as an enforcement priority. (emphasis added)

Meanwhile, the bulk of the TIGTA report suggests a less than successful effort. For example:

As shown in Figure 7, the average dollars assessed per hour on returns with TPI of $10 million or more were nearly 14 times more productive prior to the 2020 Treasury Directive. Overall, we found that the no change rate was lower and average dollars assessed per return and the average dollars assessed per hour were higher in TYs 2016 and 2017 prior to the 2020 Treasury Directive.

What to do? The good news is Treasury has abandoned Mnuchin’s “8 percent” audit rule. The bad news is the current IRS leadership appears determined to arbitrarily target large pass-throughs and other high-income returns anyway.

Meanwhile, the chorus to target rich tax cheats continues unabated in Congress. People do cheat on their taxes, but the cheating is relatively rare (we have one of the highest compliance rates in the world) and it isn’t limited to any one taxpayer class. The IRS needs to get back to dispassionately reviewing all returns and looking for specific indicators of tax evasion. If they did that, perhaps they’d have more support on the Hill.