Under the category of “Care to elaborate?” this month’s CBO analysis of the fiscal cliff costs includes estimates of the Section 461(l) excess loss provision that are, shall we say, significantly revised. The new numbers are much more believable, but they do beg the question of what took the JCT so long to rework their original estimates.

To review, the TCJA capped the ability of pass-through business owners to deduct their active business losses. Under the old rules, those losses could immediately offset other forms of owner income (wages, capital gains, investment income, other business income, etc.). This approach was consistent with the concept of an income tax, where taxpayers should be taxed on their net income. It also reflected good tax policy, as it produced counter-cyclical results – taxes on business income went up during the good times and declined during the bad ones.

Then somebody decided to cap these deductions to address…well, we have no idea what the point was. The result was Section 461(l) where any active business losses exceeding $500,000 would have to be carried forward and treated as a net operating loss in the following year. The effect was to delay, by perhaps a year or two, the ability of business owners to deduct some of their losses.

It also meant that the counter-cyclical treatment of losses was turned on its ear. Now when the economy goes south and businesses start losing money, their taxes go up, not down. That’s what is known as bad tax policy.

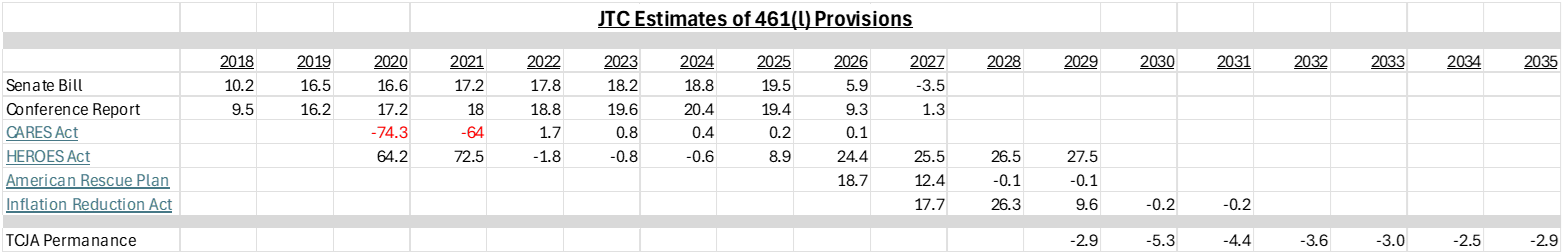

Fueling the provision were JCT revenue estimates so outrageous that almost nobody bothered to ask how a simple timing change could produce so much revenue. The initial JCT score back in 2017 was $176 billion over eight years! That was later revised down to $137 billion, but it went up again in the final conference report to $150 billion, or about $18 billion per year.

These eye-popping scores set the stage for the soap opera that occurred during the COVID pandemic.

The CARES Act was designed to help families and businesses during the COVID shutdowns. One of its provisions relaxed the net operating loss rules (including the excess loss rule) to allow businesses to get refunds from prior years. As the Obama administration described similar provisions during the financial crisis, it all was pretty standard stuff:

The Economic Recovery Act included a provision that allowed small businesses to count their losses this year against the taxes they paid in previous years. Today, the President extended that benefit for an additional year and expanded it to medium and large businesses as well….This provision is a fiscally responsible economic kick-start, putting $33 billion of tax cuts in the hands of businesses this year when they need it most, while enabling Treasury to recoup the majority of that funding in the coming years as these businesses regain their strength and resume paying taxes.

Pretty standard, except for the score. According to the JCT, a one-year suspension of the excess loss cap would reduce revenues by $158 billion! So a provision that was supposed to raise $150 billion over eight years now was going to cost more than that if it was suspended for a year? If this was true, then somebody was making out like a bandit, and it sure looked like rich people. Cue the critics. Here’s NPR:

[T]he only people that are going to benefit from this tax change are people that make at least half a million dollars in income outside of their businesses. And just to put that in context, that is literally the top 1% of U.S. taxpayers. So in other words, the government, in the CARES act, is going to give out $135 billion in tax relief only to people that make at least half a million dollars, only to the top 1% of taxpayers in this country.

And the Tax Policy Center:

Congress justified massive CARES Act tax relief for losses to infuse cash quickly to businesses, including “small” businesses. But providing cash to the wealthy via tax refunds is little more than a windfall. Congress should target relief to those truly small businesses that desperately need help.

Keep in mind the “massive” there is a reference to the JCT’s errant score, but the “windfall” critique is also in error. Say you run a large family business in a state where the governor has just mandated a pandemic shutdown. Your previously profitable business is now bleeding cash. Your doors may be closed but you still have to pay your employees and suppliers, cover rent, stay current on loans, etc. One option would be to fire everybody and ride out the crisis.

Another would be to sell other assets to stay liquid and keep people employed. If you chose the latter, as many businesses opted to do, the old rules allowed you to deduct your business losses against any capital gains you incurred from the asset fire sale. The new rules, on the other hand, would have forced you to pay taxes on income you don’t have now and postpone the deduction of your losses until after the pandemic. Brilliant.

Fortunately for all those employees, the TPC and its allies failed to cancel the CARES Act relief.

The effect of the errant scoring wasn’t limited to press releases and shallow analysis. It moved policy too. During Senate debate over the Inflation Reduction Act, a successful amendment to shield private equity from the Corporate Alternative Minimum Tax (CMAT) used a two-year extension of the excess loss limitation as its pay-for. The CAMT relief reportedly cost $35 billion, while the JCT scored the extension at $53 billion.

Fast forward to this month’s CBO report and suddenly, absent any explanation, the scores on the excess loss provision have been revised down by a factor of nearly 10.

So a policy that the JCT scored as reducing revenues by $28 billion in 2029 now magically costs the government only $2.9 billion? If only somebody had flagged this previously…

How can a one-year suspension of a “timing” policy cost the federal government this much revenue? The answer is we have no idea, but the next step in this debate should be a full accounting of the committee’s revenue estimate.

We still would like an explanation. We would also like a redo on the Inflation Reduction Act amendment. According to today’s revised estimates, that result was a fraud.

In the private sector, economic modelers who want to get published are required to be transparent and provide both their data and their methodology. Perhaps it’s time to apply these same rules to the CBO and JCT?