Jason Furman thinks the Biden Administration’s soon-to-be proposed minimum tax is a good idea. We can’t think of any reasons why.

Administratively, it will be a nightmare of complex accounting, valuation, and litigation. From the marginal point of view, they included wages and investment income into the tax base, but it will still create scenarios where the effective rates are outrageously high on America’s family-owned businesses. There’s the role inflation will play in forcing business owners to pay tax on imaginary gains. There’s the issue of exactly what we are taxing – capital – the life blood of our economy, which the President wants to tax away. And finally, there’s the underlying rationale – that rich people pay less in taxes. As we’ve written in the past, that deserves some serious scrutiny because most of the people selling that particular snake oil have been demonstrated to be really bad at math.

Let’s start with the policy itself. According to the Washington Post, the President will unveil a new “Billionaires Tax” as part of this annual budget submission. Here’s the Post’s description:

The “Billionaire Minimum Income Tax” plan under President Biden would establish a 20 percent minimum tax rate on all American households worth more than $100 million, the document says…. The White House plan would mandate billionaires to pay a tax rate of at least 20 percent on their full income, or the combination of traditional forms of wage income and whatever they may have made in unrealized gains, such as higher stock prices.

So somebody worth $100 million is now a billionaire? Inflation is getting really bad, isn’t it? Just kidding, but it is odd that this Administration can’t even get the billionaire thing right. If you’re going to have a billionaire’s tax, why not just tax billionaires? We digress.

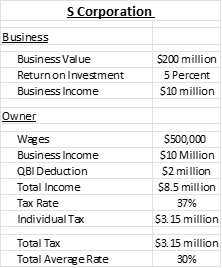

Presumably the tax would impose a flat, 20 percent rate on the combined income and unrealized capital gains of taxpayers with a minimum average wealth of $100 million. By example, consider the owner of a large S corporation worth $200 million. This owner employs hundreds of workers and the business is the economic cornerstone of a small community. If the business has an average return of 5 percent and the owner pays himself $500,000 a year, the math works like this:

This example glosses over lots of details, like progressive rate schedules, but it gives you the general idea. The owner has $10.5 million of income and pays $3.15 million in taxes, for an effective tax rate of 30 percent.

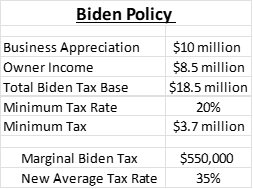

Under the Biden plan, presumably, income is redefined to include any appreciation in the value of the business. If the business appreciates by 5 percent this year, then the owner would have an additional $10 million of unrealized gains. These gains would be added to the owner’s regular income to form the tax base of the new, minimum tax. Something like this:

In this example, the result is an additional $550,000 of tax for a business owner already paying an effective tax rate of 30 percent. Aside from the obvious unfairness of penalizing a company already paying a high tax rate, this result raises all sorts of other challenges. Let’s go through them.

First, how do we decide that the value of the business increased by 5 percent? There’s a whole industry devoted to valuing illiquid assets like closely-held businesses, but until you have an actual arms-length sale, any valuation is just an estimate.

Second, where does the money come from? We currently have an income tax because income is both the best measure of how much a taxpayer is benefitting from their efforts, and it’s also a good proxy for whether the taxpayer has the resources to pay the tax.

But unrealized gains are not income. You can’t spend them. If you could, they’d be realized gains. And while the Post and other observers are fond of talking up the ability of billionaires to borrow, most S corporation owners don’t have unlimited borrowing capacity. Depending on how leveraged their business is, they might have no capacity at all.

Third, while the owner in this example has $10.5 million in income, all that income might not be in his personal bank account. For S corporations and other pass-throughs, retained earnings are taxed the same as distributed earnings. For expanding businesses, the owner is paying taxes on income that has already been committed to the business. He will have to dig into his savings or borrow to pay the rest. The Biden plan would make this dynamic worse.

Fourth, what happens when a business doesn’t make any money, but for extraneous reasons its value rises anyway? In that case, the owner will have to dig deep into his savings, or borrow significantly, in order to pay the $2 million in new tax owed on no income.

And then they’ll have to do it again next year. How long do you think this could continue until the business shuts down or, assuming there’s a market for it, the owner simply sells?

Under a previous plan put forward by Finance Chairman Wyden, illiquid assets like businesses and farms would have been exempt from the new mark-to-market approach, but would have to pay a higher tax when they are eventually sold. It will be interesting to see if the Biden folks do something similar.

Fifth, we joked about inflation earlier, but it plays an extremely negative role here too. Does the Biden Treasury adjust the tax base for inflation? If not, the proposal is a complete non-starter when inflation is at a 40-year high.

By example, home values rose 15 percent this year, nominally. In real terms, their value rose about half that, or 7 percent. Inflation accounted for the rest. But homeowners who sell their homes might still have to pay additional tax, as capital gains are not indexed for inflation. Unindexed, the Biden “billionaire” tax would have the same effect on businesses, only you’d have to pay the tax on phantom gains every year.

Sixth, when our business owner pays the tax, either by borrowing or digging into savings, the net effect is to reduce the amount of capital available to invest and create jobs. This might not be that big of a deal if it was a one-time tax but, again, this tax is due every single year that there’s appreciation, so the cumulative effect will be substantial. We should encourage capital creation, not tax it.

Finally, as we have written in the past, the narrative of the rich getting richer at the expense of the middle class has been grossly overstated and is built upon seriously flawed data and analysis. The stories about undertaxed billionaires play upon that false narrative by first redefining income to include something – unrealized gains – that’s never been considered income, and then claiming the tortured result somehow validates their position. As the Joint Committee on Taxation’s distribution tables show, the US has an extremely progressive tax code, and it’s gotten more progressive over time, not less.

As we noted at the beginning, we can’t think of any good reasons to support this idea, but we can think of lots of reasons to oppose it. Unrealized gains are not income. You can’t spend them, and you can’t use them to pay your taxes. Congress already rejected wealth taxes and mark-to-market proposals earlier this Congress. It should reject this idea too.