Last week’s on, off, and on-again bipartisan deal was confusing, but it did make clear President Biden’s intention to advance a more expansive partisan package regardless of the bipartisan bill’s fate.

Work on that expanded package has already begun. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer kicked off the budget reconciliation process earlier in the month, and Budget Committee Chairman Bernie Sanders is now in the process of putting together a spending framework, reportedly in the $6 trillion range, with $3 trillion in offsets.

With moderate Democratic Senators Joe Manchin, Jon Tester and others voicing concern over the size of the package, however, we expect any legislation moving through the Senate to be pared down significantly, including the size of any potential tax hikes. What might that look like? Here are some guiding observations:

- The Biden Double Death tax (imposing capital gains at death) is on life support. The policy has unified the business community in opposition and an impressive number of Democrats have come out against it as well (here, here, and here).

- Without the Double Death tax, taxing capital gains at ordinary rates would lose rather than raise revenue due to the so-called “lock-in effect.” In its place, tax writers would likely pare back the rate to the revenue maximizing level of about 28 percent.

- Striking the Double Death tax from the package and taxing capital gains at rates lower than ordinary income would bring carried interest and estate tax changes back into the conversation.

- There’s also the lingering question of how to address state and local tax (SALT) deductions – an issue that has emerged as a “red line” for some 30 House Democrats. The Biden administration has remained agnostic but has indicated any relief would need to be offset. Full repeal of the SALT cap is expensive ($300+ billion) and benefits mostly upper-income families, so some sort of compromise is likely. The need to offset SALT cap relief would likely focus the tax writers’ attention to changes in the estate tax and 199A deduction.

- Finally, on the corporate side, Manchin is on record as supporting no higher than a 25 percent rate, which is a likely ceiling. And while the Biden administration initially proposed raising the U.S. minimum tax (GILTI) rate from 10.5 percent to 21 percent, recent comments from Treasury suggest the final number might be much lower.

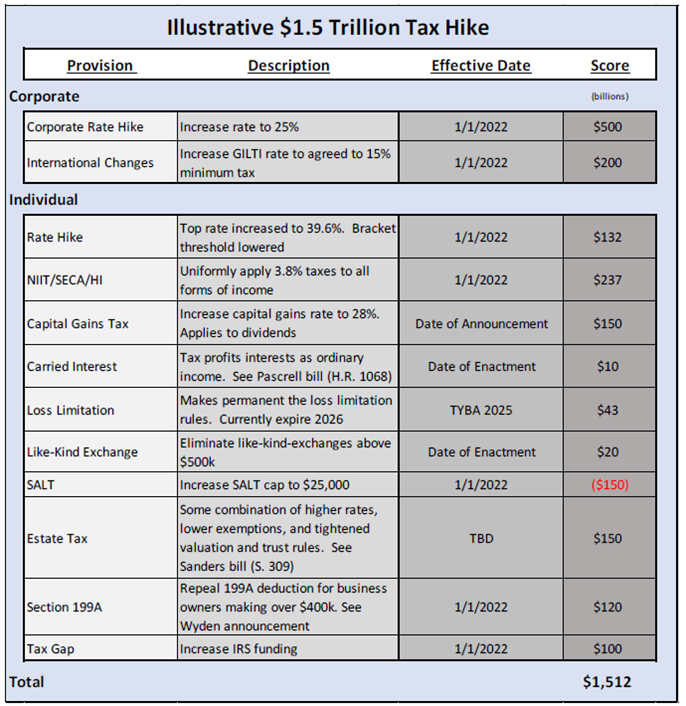

With all that in mind, we put together the following table showing what a pared-down, $1.5 trillion package might look like. This illustrative package is speculative, obviously, but we think it does a good job of showing what the reconciliation package currently being crafted might look like:

The purpose of this exercise is not to endorse the policies listed here, but rather to make clear to the business community that even a pared down tax package represents a significant threat to private companies and the communities they serve.

How much of a threat? This second table shows the impact on private verses public companies. As you can see, even without calculating the marginal effects of any estate tax changes, individually- and family-owned businesses will end up paying much higher marginal rates on a much broader base of income.

In short, this should serve as a roadmap of what to oppose in the coming months. The worst aspects of the Biden tax plan may be on life support, but that doesn’t mean the danger has passed. This combination of high marginal rates applied to a very broad tax base makes up the first of what S-Corp has termed the “triple threat” posed by the Biden plan to private companies – higher taxes when the business earns income, higher taxes when the business is sold, and higher taxes when the business is passed on to the next generation.

The illustration demonstrates the importance of the 199A deduction for pass-through employers. Without the deduction, tax rates on pass-throughs businesses will rise sharply, even compared to pre-TCJA, and be applied to a much broader base of income.

It also demonstrates how private companies are hit harder than public companies. Increasingly, public companies are owned by tax exempt or tax advantaged shareholders, which means the traditional double corporate tax – and the increased capital gains and dividends taxes – doesn’t really apply to them. Under the illustrative plan, public companies will consistently pay a lower tax than private companies, regardless of how they are organized.

Public companies are also largely immune to the adverse effects of the estate tax. While individual shareholders may be subject to the estate tax, the companies themselves are shielded from the direct effects of the tax. Aside from a possible marginal increase in their cost of capital, the estate tax has little or no impact on their operations or decision making.

Once private companies reach a certain size, on the other hand, the estate tax looms large in all of their planning and operations. As one of our members observed, the estate tax forces private companies to buy back a portion of the business from the government every generation. The illustrative plan would increase that cost sharply, even without the capital gains at death provision.

The COVID pandemic and the government’s health and monetary response to it has accelerated the consolidation of economic activity into a few, very large public companies. While Main Street got shut down, Wall Street got an interest rate cut. The illustrative plan shown here would exacerbate that trend, sharply raising taxes on private companies and making it increasingly difficult for them to survive from one generation to the next. The business community is unified in opposition to any tax hikes on employers this Congress. It should be.