With impeachment over, congressional Democrats are turning their attention to their $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief bill. House committees spent prior weeks marking up pieces of the bill, which will be consolidated into a single “reconciliation” package by the Budget Committee today and then considered by the full House later this week.

For the Main Street business community, the process here is as important as the policy. The congressional majority chose to use reconciliation to move their COVID relief package, which raises several issues worth highlighting.

Senate Rules Under Pressure

The primary benefit of using reconciliation in the Senate is the ability to pass a bill with a simple majority. But at least one provision in the House bill — the $15 minimum wage hike — appears to violate the Senate’s reconciliation rules, which prohibit “extraneous matters.” Unless the majority takes out that provision, any Senator can raise a point of order against it and ask the Chair for a ruling.

Waiving the Chair’s ruling requires 60 votes. As with the filibuster rules, however, the Chair’s ruling can be overturned — and a new Senate precedent set — by a simple majority vote using Rule XX. That would open up the reconciliation process to all sorts of legislative initiatives – not just taxes and spending – and be akin to eliminating the filibuster in the Senate, only worse. In this case, the benefit would accrue only to the majority, since they control the budget process. The minority would still live in a world where they need 60 votes to move their priorities. This is a big deal — not just for the prospects of the minimum wage, but for the future.

Senators Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) made clear they would oppose killing the filibuster, but does their pledge extend to preserving the reconciliation rules too? Does a pledge made in a vacuum still hold when there’s real policy on the table? Manchin and Sinema oppose the minimum wage hike, so it may not be a good test. Nonetheless, the upcoming reconciliation debate will be the first indication of how far Senate leadership is prepared to go, and how hard they are willing to push their members, to change long-standing Senate rules to enact their priorities.

Going Big

Congressional leadership has access to two budgets this year (Congress didn’t pass one last year) and therefore two reconciliation bills. By using reconciliation on what could have otherwise been a bipartisan COVID package, they’ll only have one shot left this year to move legislation with a simple majority. By all accounts, they plan to use that on a big infrastructure/climate/tax bill, with the emphasis on BIG. According to the Washington Post:

“Senior Democratic officials have discussed proposing as much as $3 trillion in new spending as part of what they envision as a wide-ranging jobs and infrastructure package that would be the foundation of Biden’s ‘Build Back Better’ program, according to three people granted anonymity to share details of private deliberations. That would come on top of Biden’s $1.9 trillion relief plan, as well as the $4 trillion in stimulus measures under former president Donald Trump. Aides cautioned that the spending figures were highly preliminary and subject to change.

“But unlike under Trump, when multiple efforts to address infrastructure faltered before getting off the ground, Biden is expected to take a big swing at the issue and package together funding for expanded broadband networks, bridge and road repairs as well as technology that reduces greenhouse gasses in a sprawling bill that threatens to enlarge to encompass multiple other issues as well.”

So this all suggests that the next reconciliation bill is going to be a very BIG bill, with many of the proposed policies rekindling the debate over what is and what is not allowed under reconciliation. We expect the Senate’s history of needing 60 votes to pass legislation will again be under pressure.

Tax Outlook

What does this mean for tax policy? Right now, the size of the tax title appears constrained by the following dynamics:

- First, there appears to be a very real aversion among tax writers on both sides of the Capitol to large tax hikes at a time when the economy is struggling.

- Second, Democratic Leadership appears only loosely concerned with offsetting any increased spending contained in the package. They would love to minimize the package’s deficit impact, but do not feel the need to cover it all.

- Third, the Senate is evenly divided 50-50. Unless the Majority Leader can attract moderate Republicans to cross over and support the effort, he will need every single Democrat to support the package. This means the most moderate Democrat will define the size and policies considered by the Senate.

Those dynamics, however, are countered by these:

- As it is the last train, the BIG Bill will be seen as the best and perhaps only shot to enact numerous policies before the mid-term elections. Progressives in particular are going to push hard to include the Biden tax proposals and beyond.

- The timing for this second package is uncertain. While consideration could happen as early as this spring, we’re hearing it could easily leak into the fall. The longer it waits, the bigger its likely to get.

- We have been inundated with reports on how big economic growth is going to be later this year. What is underappreciated is how much of this growth will be due to massive deficit spending by the federal government. The pending COVID bill and last year’s CARES Act will inject trillions into the economy this year, juicing growth significantly in a $21 trillion economy. It may just be a sugar high, but a big GDP number in the second quarter could undermine concerns that large tax hikes would hurt the economy.

- Finally, after 40 years of disinflation, deficit hawks may finally have some inflation signs to point to. If the 10-year continues its rise, it will give moderates ammunition that a higher percentage of the new spending needs to be offset.

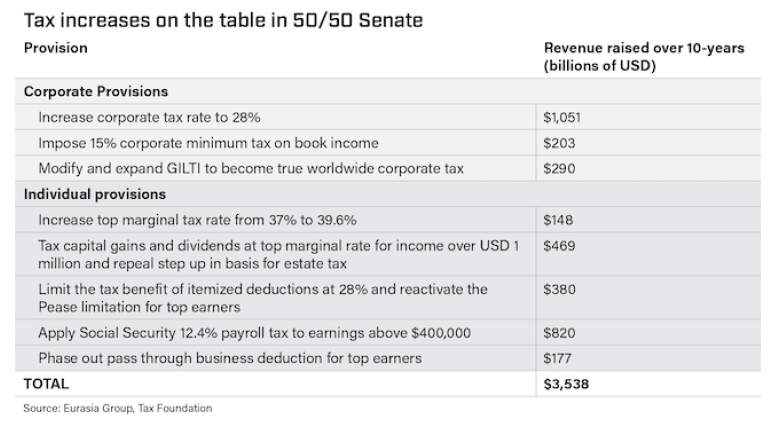

All that suggests the tax title in the BIG bill is going to be robust, include a large portion of the Biden Tax proposals from the election, and maybe a little bit more. As a reminder, here are the broad provisions in the Biden Plan (courtesy of the Eurasia Group):

As you can see, the Biden plan is sufficiently large to offset the entire $3 trillion infrastructure package anticipated by the Washington Post. At this point, we’d guess about half that much is locked in – including most of the corporate tax hikes – and the longer we wait, the more provisions will get added.

What’s the “little bit more”? Finance Chair Ron Wyden (D-OR) has been working on his “mark-to-market” approach on capital gains for several years, Senators Sanders (D-VT) and Warren (D-MA) will push their wealth tax, and there will be a strong, and perhaps bipartisan, push to include some sort of carbon tax. Finally, the CARES Act NOL relief continues to be a lightning rod and, at least according to the JCT, would raise lots of retroactive revenue. None of these is likely to be enacted, but all will be debated.

In terms of effective dates, the longer Congress waits to act, the more likely the effective dates will be pushed back to date of introduction, date of enactment, or even next year and beyond. Some policies might be made effective January 1 of 2020, but that is unlikely to include the capital gains or estate tax provisions. For those members worried about raising taxes when we’re still in a pandemic, having them take effect is the future is an obvious solution.

Conclusion

So expect the next reconciliation bill to be big. It will be viewed as the last train out of town and everybody will want to catch a ride. The bill should include a tax title that both addresses the demands of progressives to raise taxes on big corporations and the wealthy, and the need to at least partially offset the new spending included in the bill. That would suggest a big tax title.

Will it pass? We will have to see, but the private business sector faces two distinct threats. First, an erosion of the Senate rules that would open the reconciliation process to more types of legislation and, second, a tax title that will raise rates on pass-through income, business sales, and estate taxes. More on this in the coming weeks.