Where does fairness lie? At a time when Main Street is struggling to stay open while Wall Street flies high, you might be surprised that Bloomberg thinks it’s private companies organized as S corporations and partnerships that have the advantage, at least when it comes to taxes.

The Bloomberg story at issue reviewed the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act and whether it lived up to the promises made by its sponsors, including the goal of balancing out the tax treatment of private and public companies. Here’s the key graph:

“Just in terms of fairness,’ the pass-throughs still have an advantage,” said Richard Prisinzano, director of policy analysis at the Penn Wharton Budget Model. “It’s just been diminished.”

Let’s review what’s missing here. First, the 39.8 percent C corporation rate cited is the combination of the new 21 percent corporate rate and the 23.8 percent tax on capital gains and dividends. That is what a C corporation would pay if 1) all the shareholders of the corporation were fully taxable and 2) all the earnings of the corporation were distributed in the same year as they were earned.

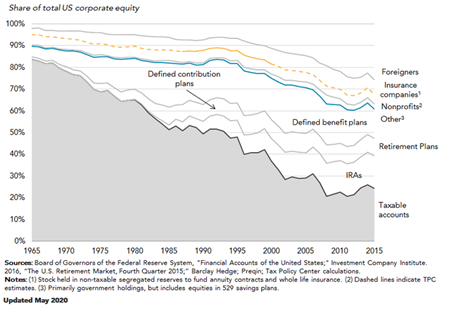

But most C corporation shareholders don’t pay taxes, or they pay sharply reduced tax rates. According to the Tax Policy Center, the share of U.S. corporate stock held in taxable accounts has fallen from more than 80 percent in 1965 to about 25 percent in 2015.

The traditional concept of the corporate double tax is a relic – most corporate earnings today avoid the second layer of tax.

Taxable shareholders also avoid the full double tax. Not all corporate earnings are distributed when they are earned. Some companies, like Berkshire-Hathaway, are famous for never paying dividends. Deferred taxation also has the effect of reducing the marginal effective tax rate paid by public corporations. As the Tax Policy Center notes:

C-corporations can also choose to retain their earnings rather than pay dividends. The corporation would still pay the corporate income tax on its earnings, but the shareholders would defer the second round of taxation until either the corporation distributed the earnings sometime in the future or the shareholders sold their stock at a price that reflected the value of the retained earnings. Deferral of taxation reduces the present value of its burden.

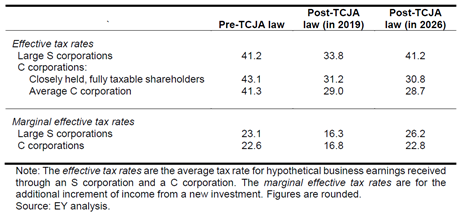

So that’s the corporate side of the ledger. We know the Bloomberg graph is wrong – the average tax rates paid by corporations are not 39.8 percent — nor are they 21.0 percent. They are somewhere in the middle, and their level depends on the identity of the corporation’s owners and its dividend policies.

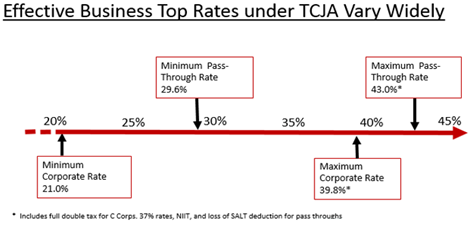

Meanwhile, the pass-through tax rate is generally higher than what Bloomberg depicts. Yes, some companies pay the 37 percent rate, less the full 20 percent pass-through deduction, but that’s not always the case, nor is it even the typical case. Larger pass-throughs in particular are subject to three different “firewalls” on the amount they can claim as income qualifying for the deduction – there’s the exclusion of so-called specified services businesses or income derived from those services, a limitation based on the wages paid by the company, and finally a limitation tied to the owner’s taxable income.

The net result is that even companies with lots of pass-through income might not receive the full 199A deduction, or any deduction at all. As with C corporations, their ultimate tax rate depends on their size, industry, how many workers they employ, and other factors, and it ranges between 30 percent and something in the mid-40s.

So where does fairness lie? Two years ago, we asked EY to take into account all of the above and estimate the rates for both large pass-through businesses and C corporations. The result, which we fully explored here, is that the tax rates on pass-through businesses are slightly higher than those of C corporations, but only when the 199A deduction is available. When it goes away in 2026, C corporations will have a huge advantage. C corporations with lots of tax-exempt shareholders will do even better.

This is an old debate, and we’ve covered it repeatedly. At a time when you can drive through entire blocks of private businesses boarded up and empty as the radio blares about the new record high prices on Wall Street, it’s particularly critical we get it right.

Pass-through businesses advantaged in the tax code? Hardly. Not in normal times, and definitely not now.