We interrupted our impeachment viewing last week for a Brookings Institute briefing exploring various ways the Congress could raise taxes. A book of revenue raising recommendations accompanying the briefing weighed in at a hefty 368 pages. According to the book’s editors, “This book is about taxes. It poses a simple question: Given that the United States needs more revenue, how should we raise it?”

It’s too early for us to digest all 368 pages, but the book raises one issue that’s worth exploring from the onset – the progressivity of the U.S. Tax Code and which direction we’re headed. In recent years, there’s been a concerted effort to paint the U.S. Tax Code as insufficiently progressive. Brookings and their Tax Policy Center have apparently joined that chorus. Here’s what the book’s editors say:

[M]ost of these new revenues must come from those best able to pay, especially since tax cuts benefiting the highest earners account for so much of the declining share of taxes paid at the federal level. Since the late 1960s, the share of federal revenue paid by working Americans in the form of payroll taxes has increased from just over 20 percent to 35 percent. Yet corporate tax collections have plummeted from more than 25 percent to less than 10 percent of revenues, and the top rate paid by wealthy filers has fallen from 70 percent during Lyndon Johnson’s presidency to 37 percent today. And over the last two decades, Congress has hollowed out the estate tax to such an extent that only 0.2 percent of estates pay any tax at all.

So the Tax Code has gotten less progressive since 1960? Probably not. In recent months, it has become increasingly clear the case for a “regressive” Tax Code rests heavily on cherry-picked statistics and faulty estimates. When you account for those flaws, today’s Tax Code looks more progressive, not less.

On the cherry-picking front, look again at the facts cited by the Brookings’ editors. Each is correct in its own narrow sense, but they hardly comprise the totality of changes made to the tax code over that time. Top rates certainly came down, but as we’ve noted before, reducing rates nobody paid is hardly regressive, especially when they were coupled with base-broadening measures and new refundable tax credits that eliminated tax liabilities for millions of low-income families.

To understand the totality of tax code changes and their effect on tax burdens, you can skip the cherry picking and go right to the Tax Policy Center’s own distribution tables. Here’s what they say (they only date back to 1979):

So after 40 years of changes, low- and middle-income taxpayers pay significantly less of the total tax burden, and the wealthy pay significantly more. That’s the opposite of regressive.

Obviously, the folks at the Tax Policy Center are aware of these numbers – this is from their table — so how do they explain the disconnect? Here’s one explanation from a 2012 Brookings paper:

In 1979, the top 1 percent of Americans earned 9.3 percent of all income in the United States and paid 15.4 percent of all federal taxes. While the share of income earned by the top 1 percent had more than doubled by 2007—to 19.4 percent—the share of federal tax liability paid by that group only increased by about 80 percent, to 28.1 percent. The share of taxes increased less for this group because high-income tax rates fell by more than the tax rates for everyone else—reductions that made the system less progressive.

The burden on the rich went up, and they paid more, but not as much as their income changed, so that’s regressive? This measure of progressivity focuses on incomes, not tax burdens. That’s not what most people have in mind when they are told that the tax code has become less progressive.

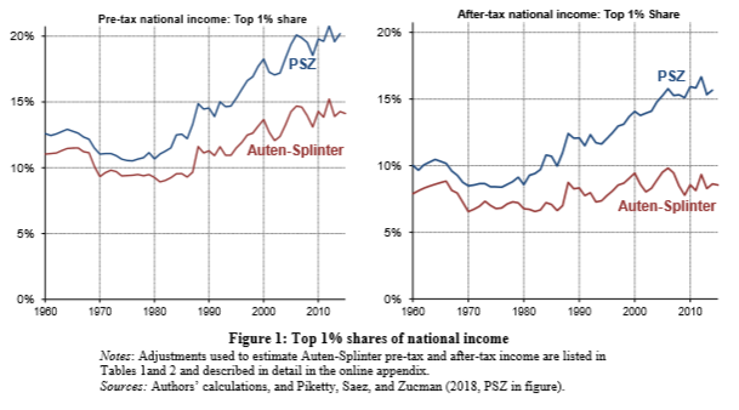

Moreover, the income estimates cited here are deeply suspect. Did the income share of the top 1 percent really rise from 9.3 percent to 19.4 percent between 1979 to 2007? Probably not. Last year’s seminal paper by Treasury economist Gerald Auten and Joint Committee on Taxation economist David Splinter demonstrated that these income estimates are deeply flawed:

Top income share estimates based only on individual tax returns, such as Piketty and Saez (2003), are biased by tax-base changes, major social changes, and missing income sources. Addressing these issues requires numerous assumptions, especially for broadening income beyond that reported on tax returns. This paper shows the effects of adjusting for technical tax issues and the sensitivity to alternative assumptions for distributing missing income sources. Our results suggest that top income shares are lower than other tax-based estimates, and since the early 1960s, increasing government transfers and tax progressivity resulted in little change in after-tax top income shares.

Here’s an accompanying chart comparing estimates by academics Piketty, Saez and Zucman, with those by Auten and Splinter. The estimates show the importance of accounting for the missing items, as well as the critical role taxes play in reducing the concentration of income. Contrary to the Brookings view, taxes appear to play a growing role in leveling out income growth at the top.

The most significant tax policy change reflected in these revised estimates is the shift from C corporations to pass-through businesses. Reductions in individual rates in the 1980s allowed private companies to move away from the harmful double corporate tax and towards the pass-through single tax system. These changes resulted in an explosion of business activity, higher levels of capital investment, and more jobs.

The most significant tax policy change reflected in these revised estimates is the shift from C corporations to pass-through businesses. Reductions in individual rates in the 1980s allowed private companies to move away from the harmful double corporate tax and towards the pass-through single tax system. These changes resulted in an explosion of business activity, higher levels of capital investment, and more jobs.

They also shifted income onto the personal returns of all those business owners. Estimates by Piketty et al. fail to take this shift into account when measuring income inequality, and it totally skews their results. Here’s Auten and Splinter:

The reform also motivated some corporations to switch from filing as C to S corporations and to start new businesses as passthrough entities (S corporations, partnerships, or sole proprietorships), causing more business income to be reported directly on individual tax returns. This is because all passthrough income is reported on individual tax returns while C corporation retained earnings are not. Before TRA86, the top individual tax rate was higher than the top corporate tax rate (50 percent vs. 46 percent), allowing certain sheltering of income in C corporations with retained earnings. This incentive was even larger when the top individual rate was 70 percent in the 1970s and 91 percent before 1964. TRA86 lowered the top individual tax rate below the top corporate tax rate (28 vs. 34 percent), reducing the incentive to retain earnings inside of C corporations and creating strong incentives to organize businesses as passthrough entities. Our analysis accounts directly for the limitations on deducting losses and indirectly for the shift into passthrough entities by including corporate retained earnings. This leads to important findings for in the 1960s and 1970s, when high individual income tax rates created strong incentives to shelter income inside corporations. Without these corrections, top income shares are understated before 1987. [Emphasis added.]

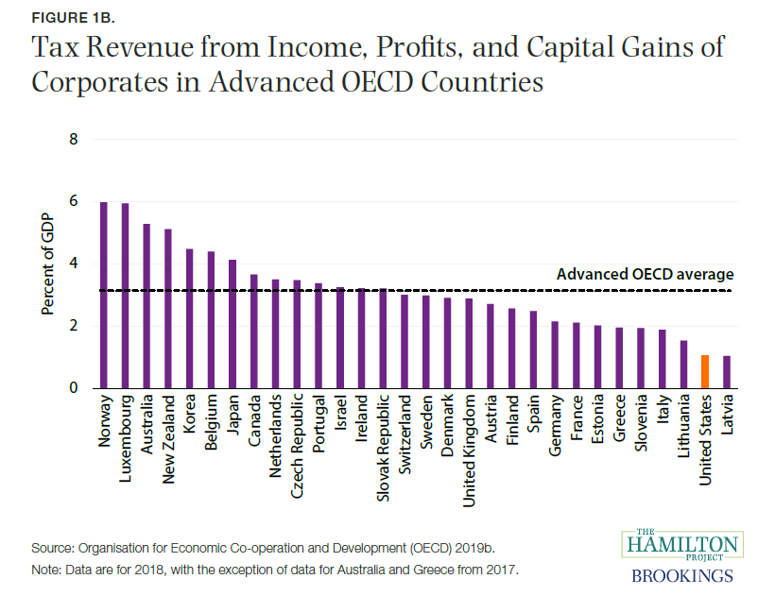

It also exposes the flaw in the prevailing perception that the corporate tax base is “plummeting.” Harvard Economist Jason Furman uses this argument to justify raising the corporate rate. This chart from his chapter in the book shows just how much our corporate tax collections lag behind the rest of the world.

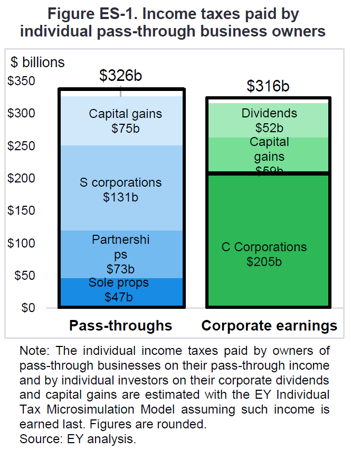

But the rest of the world doesn’t have a robust pass-through business sector. Pass-through businesses pay taxes too, often at higher individual rates than C corporations, and when you account for those taxes, that “plummet” looks more like a steady state.

As our recent EY study showed, pass-through businesses pay more in taxes than C corporations, so including them in the corporate numbers would more than double to total tax paid by businesses. Only focusing on corporate payments is misleading. To get an accurate picture, tax economists should look at taxes paid by the entire business sector.

So that’s it – including the totality of tax changes and income sources makes clear the Tax Code has become more, not less, progressive in recent decades. Will this change the prevailing narrative from Brookings and the Warren and Sanders campaigns? Probably not. As the editors of the Brookings book make clear, the goal of this exercise is not to question the prevailing economic wisdom, it’s to raise taxes.