The Peterson Institute held a “Combating Inequality” event last week that included a vigorous debate over wealth taxes. The heavyweight match between Emmanuel Saez – the leading advocate for wealth taxes these days – and Larry Summers in particular is worth watching.

One aspect missing from the debate, however, was how wealth taxes would handcuff successful private businesses. Summer briefly touches on the challenge his family’s hardware store would have paying the tax, but there is so much more to it. Wealth taxes:

- Are far larger than their headline numbers suggest;

- Paid on top of all existing taxes;

- Hit hardest when the economy is bad; and

- Target illiquid, private companies the most.

Add it all up, and it’s hard to see how successful family businesses can survive an aggressive wealth tax.

Wealth Tax — Bigger than it Looks

Senator Elizabeth Warren likes to describe her plan as just “two cents” but it’s so much more than that. The tax would be two percent on the cumulative wealth of families worth more than $50 million, and three percent on those worth more than $1 billion.

So a family business worth $100 million would pay $2 million dollars, per year, every year. Two million dollars a year is obviously a lot of money, but to understand the scale of the tax, you need to compare it to an income tax. As AEI scholar Alan Viard wrote for the Aspen Institute:

A useful way to interpret wealth tax rates is to translate them into equivalent income tax rates. For a taxpayer who holds a long-term bond with a fixed interest rate of 3% per year, a 3% per year wealth tax is equivalent to a 100% income tax because the tax captures 100% of the taxpayer’s interest income. Similarly, an 8% per year wealth tax is equivalent to a 267% income tax.

The tax-rate translation is more complicated for risky investments. Suppose that, alongside her holdings of the 3% bond, the taxpayer holds a stock with an annual return that could fall anywhere between 2–10%, with an expected value of 6%. The 3% per year wealth tax could end up being anywhere from 30–150% of the stock’s return. It is not immediately clear what income tax rate the taxpayer would perceive as equivalent to the wealth tax in advance, when the stock return is uncertain.

As Alan notes, returns on capital vary, but if the average return on capital in the US is 6 percent, then the Warren tax is the equivalent of a 33 percent income tax rate, not 2 percent.

Pro-Cyclical

While investments might earn 6 percent on average, they can lose money too. The wealth tax doesn’t account for losses – the tax is owed whether an investment earns positive returns or not. This “pro-cyclical” aspect of the wealth tax is particularly dangerous, as it can force investors to divest their capital interests at times when the economy is doing poorly, encouraging a vicious downward cycle.

To counter this issue, the Warren tax allows tax payments to be deferred for five years, with interest. This provision mitigates the worst cyclical aspects of the wealth tax, but it doesn’t eliminate them. The tax is still owed, after all. For the family business worth $100 million, they could defer payment of one year’s tax for five years, but then they would owe $4 million in year five, plus interest on the deferred payment of $2 million. It’s effectively a loan that lenders will take into account when assessing the credit worthiness of the business. For credit constrained companies, there’s a limit to how much they can borrow.

What if the business loses value over the five years the tax is deferred? Income taxes account for losses. A business that loses money in year two can get a refund for the taxes paid in year one. The idea is to accurately measure and tax the income of the business over time. This approach has the benefit of being counter cycle, meaning the income tax provides refunds when the economy is soft and business lose money, and taxes them when they earn money. Even with deferral, a wealth tax doesn’t have this valuable feature.

Layer upon Layer of Tax

The Warren wealth tax is layered on top of other taxes, so a 2 percent bond would be subject to both the wealth tax and the income tax. For a $100 bond that pays 2 percent, the income tax is 82 cents (the 37 percent income tax plus the 3.8 percent NIIT), while the wealth tax is $2 dollars. The bondholder is losing 82 cents for every $100 in bonds they hold, every year. If it’s a 10 year bond, then the bondholder will be left with just $91.80 of the original $100 they invested. Instead of earning money on the investment, they lose it.

For private businesses, the layering effect will be similarly harmful. A 2 percent wealth tax is equal to a 33 percent income tax on a business earning 6 percent, which would be paid on top of the existing income taxes. In last year’s report, EY estimated the top marginal tax rates on S and C corporations were effectively equal at around 33 percent. For a successful S corporation earning 6 percent profits, then, the effective tax on its earnings, on average, would be 66 percent.

Those businesses will also be subject to the estate tax. Every generation, they will be required to buy back a portion of their business from the federal government. At a 40 percent estate tax rate and a $12 million exemption, the tax on the $100 million business could be more than $30 million. Estate planning can help to reduce this tax and spread the costs out over time, it’s still a cost private companies will have to shoulder. If the total tax ends up being $20 million and the company passes from one generation to the next every 30 years, the annual tax would be an additional $666,000 a year, on top of the $2 million in income taxes and the $2 million in wealth taxes. The company’s effective rate is now 78 percent.

Bullseye on Private Businesses

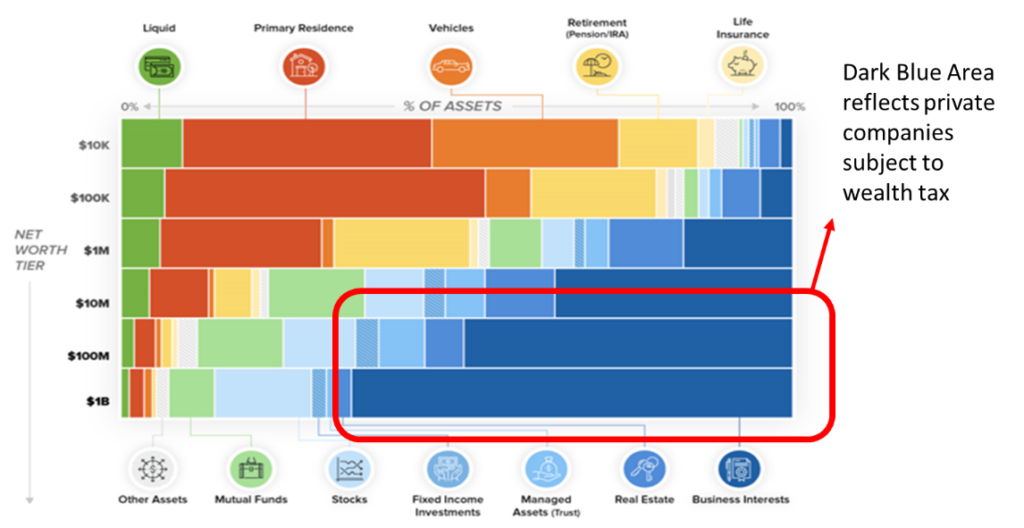

This chart from the Visual Capitalist illustrates how the wealth tax targets private businesses. Most multi-millionaires or billionaires are not liquid and most of their wealth comes from private business interests. See all that dark blue area in the bottom two income categories? Those are private businesses that will need to pay the Warren wealth tax of 2 or 3 percent per year. They will owe the tax whether the business is profitable or not.

Private vs Public Businesses

So private companies are n the bullseye of the wealth tax. Public companies, on the other hand, are largely immune to it. Public companies have access to capital from many sources – charities, pension funds, retirement accounts, and foreign investors – not easily accessible to private companies, and nearly all of these investors are not subject to the wealth tax.

To be clear, some corporate shareholders might be subject to the wealth tax, but it’s unlikely it will have any impact on their planning. At most, the corporation’s cost of capital might rise slightly as its billionaire shareholders sell off stock to pay the tax, but the effect will only be slight as the public stock markets are extremely liquid and open to so many alternative sources of capital.

In contrast, a single shareholder S corporation worth $100 million is, by definition, subject to the wealth tax on its entire valuation and it’s generally the person who runs the company who pays the tax. There’s no “arms length” separation between the taxpayer and the company.

Just how would they pay the tax? Private companies tend to be illiquid and the market for partial stakes in a private company stock is all but non-existent. Selling off a “few shares” to pay the tax is not really an option. Few investors are interested in buying a non-controlling interest in an illiquid asset, and as a result minority stakes of these businesses often sell at steep discounts compared to controlling stakes.

Falling Valuations

The wealth tax will require private companies to get valuations every year even as the tax drives down those valuations.

Think about it this way – for a certain level of risk, an investor needs to earn 4 percent after-tax on their investment. A business that fits that risk level and makes $6 million pretax would be worth $100 million to the investor. It would return 6 percent pretax, and 4 percent post tax. With the Warren wealth tax, however, the business only returns 2 percent – 6 percent minus the 33 percent income tax and the 2 percent wealth tax. For that rate of return, the investor is only willing to pay $50 million.

Not all private businesses will lose half their value, of course. The challenge to estimating declines in asset values under a wealth tax is that it doesn’t apply to all taxpayers, just those whose wealth exceeds a certain threshold. To a buyer not subject to the wealth tax, the business still is worth $100 million. The dilemma is that a single buyer won’t be able to buy the business at that price, since they would be subject to the wealth tax. Meanwhile, a group of buyers could buy the business with each of their stakes below the wealth tax threshold, but they would insist on steep discounts for lack of control, as they each would be purchasing a minority stake in the business.

Who could buy the business at something approaching its previous valuation and still avoid the tax? Private equity and public corporations come to mind. Private equity because they can raise capital from diverse sources but can still enjoy a controlling stake in the business, and public corporations because, as discussed above, they are largely immune to the tax. Individuals and families, on the other hand, would be locked out.

Economic Consolidation

This combo platter of excessive tax rates, counter-cyclical applications, broad exposure, and uneven application will result a wholesale migration of business activity into the public corporate sector.

Family-owned businesses over a certain size would begin to disappear – they either would be sold to public corporations or private equity firms with large, diverse investor bases, or they would continue on at a competitive disadvantage, paying effective tax rates more than twice what a public company pays. In the end, the wealth tax would cause increased concentration of business activity and decision making.

The irony is that S corporations were created 60 years ago to counter this consolidation. As it says on the history page of our website:

At the same time, Republicans and Democrats were increasingly alarmed that too much economic power was being consolidated into the hands of a few wealthy, multinational corporations. This economic centralization was characterized by economists like John Kenneth Galbraith, who saw America’s economic future as a grand balance of power between Big Labor, Big Business, and Big Government. Private enterprise was viewed as a thing of the past.

In response to these concerns, Eisenhower embraced the Treasury proposal and recommended the creation of the small business corporation to Congress. In 1958, led by Democratic Finance Chairman Harry Byrd, Congress acted on Eisenhower’s recommendation, creating subchapter S of the tax code as part of a larger package of miscellaneous tax items.

Be sure to watch the Peterson Institute event and the debate between Saez and Summers. It’s very compelling, even if it does underemphasize one of the key challenges of implementing the wealth tax – the existential threat it poses to successful, private companies.