The American Enterprise Institute has a new“Trump Tax Reform Blog” series on its website. Over the next month, tax policy folks from both sides will weigh in on the reform and whether it’s working. You can read the current posts here. Our invitation to comment must have got lost in the mail, but no worries, it’s a brave new world and we can comment anyway. Here’s our report:

Has the TCJA helped American workers and businesses with additional economic growth? Such questions are impossible to answer with absolute certainty, since we will never know what the economy would have done without the TCJA’s adoption. The counter factual is an elusive beast.

That said, a solid case can be made that the TCJA has enabled our long-in-the-tooth economic expansion to continue with more energy, more investment, and higher wages, than it would have otherwise.

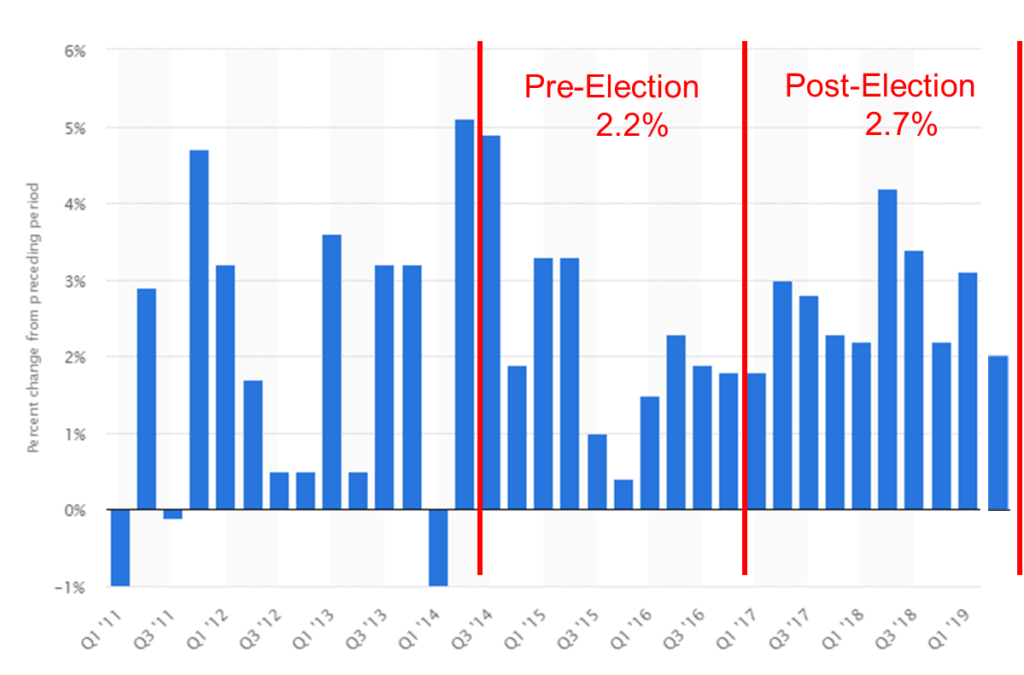

First, let’s start with economic growth. Jason Furman argues that the six quarters following the TCJAs adoption were slower than the six that preceded it. This is the wrong comparison, however. The counter factual might be elusive, but we know markets are forward looking. As soon as Trump was elected, business owners began to factor in expectations of a sizeable tax cut together with other pro-growth fiscal policies.

So the correct comparison would be the ten quarters prior to Trumps’ election verses the ten quarters that have followed it. You could include some sort of discount for the four quarters that followed the election but preceded the TCJAs adoption, since those quarters reflect an expectation of tax cuts rather than their reality, but we’re not sure that’s right. Wouldn’t investments made in the anticipation of tax cuts be just as valid as those made once it’s adopted?

So how does the correct comparison look? Pretty good for the TCJA. The pre-election average was 2.2 percent, while the post-election average is up at 2.7 percent. Half a percentage point of additional growth is significant, but the reality might be better than that. Take a look at the table below. Economic growth in the years prior to Trump’s election was a roller coaster ride of highs and lows, despite the fact that the economy was coming out of a financial crisis where you’d expect to see more consistent — and higher – growth levels. Despite coming six years into the expansion, the post-election growth numbers are more consistent, stable, and positive.

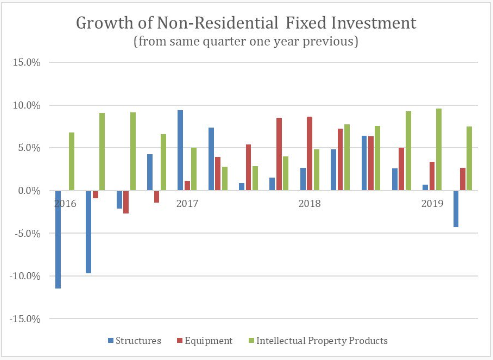

Second, let’s look at timing. Much of the economic pop of the TCJA comes from the combo platter of lower rates, full expensing, and international reforms designed to increase capital investment. But the American economy primarily is made up of consumption, so higher capital investment levels will only have a small immediate impact on the growth data. Their real contribution comes over time, as increased investments generates more jobs and higher wages. So how is Capex doing since Trump took office?

As Doug Holtz-Eakin recently wrote, it’s up consistently across the board for structures, equipment and intellectual property. Here’s the chart he used:

These higher levels of Capex promise better jobs and higher wages in the future, but just two years following adoption of the TCJA, its simply too early to see that in the economic data. We’ll just have to wait.

Third, a discussion of economic growth under Trump would be incomplete without a discussion of his trade policies. Just as the deregulation under Trump has helped spur economic activity, the trade battles he’s waged against Mexico, Canada, Europe, China – well, just about everybody – have instilled uncertainty and held back growth. CNBC had an excellent discussion of our trade challenges the other day, particularly regarding China and their recent history of stealing our intellectual property. The take-away from the conversation was that a stand-off with China was long-overdue. But the fact that our trade war with China may be justified doesn’t stop it from retarding growth and job creation, at least in the short term. Anyone reviewing the growth data over the past two years needs to take our trade policies into account when measuring the success of the tax cuts.

Our fourth observation is that the TCJA included many moving parts, with some of those provisions imposing short-term costs on the economy. A good example are the international reforms. The move from a world-wide tax system to a quasi-territorial system may be good for investment and growth in the long term, but businesses are still learning how the new rules work and many need to adjust their operations to fit the new regime. Both impose transition costs that should be taken into account. Over time, those transition costs will fade away.

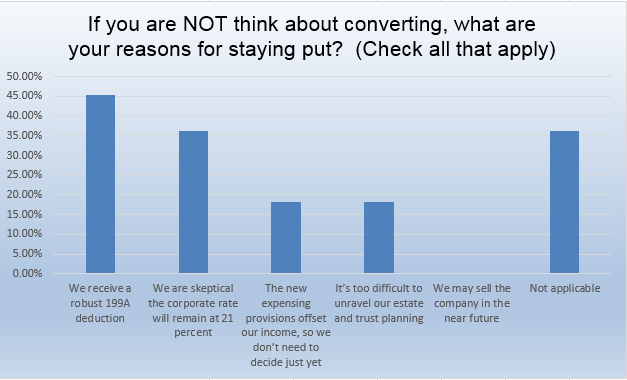

Which brings us to our fifth observation – permanence. One item that popped from our member survey earlier this year is how many S corporations decided not to convert to C this year because they didn’t have confidence the 21 percent corporate rate was going to be around for long. This feedback was slightly ironic, as it’s the Section 199A pass-through deduction that’s temporary, not the lower corporate rate. It is counter intuitive that companies would choose to stick with the temporary policies because they don’t believe the “permanent” rates will survive long. Businesses don’t make long-term plans based on temporary tax policies. If Congress wants to see the full benefit of the TCJA, they need to convince the business community that these policies are going to be around for a while. The right first step in that direction would be to make the 199A permanent.