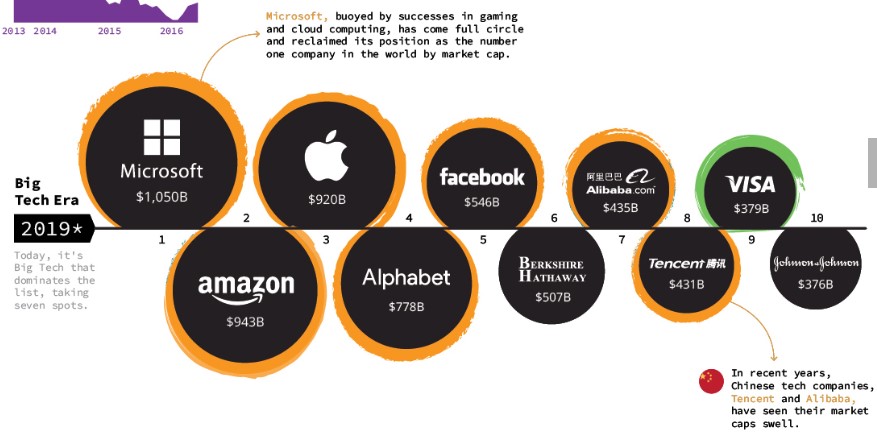

The visual economist issued another great chart last month, this time showing the largest public companies by market cap.

Our first reaction is, wait, Microsoft is number one? When did that happen? All the focus on FAANG stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google) and stodgy old Microsoft is bigger? Go figure.

Our second reaction is “Gee Grandmother, what big market caps you have.” These companies are huge! And that’s not limited to the ten companies illustrated here. Measured against GDP, the market cap of all public companies in the US has tripled since 1986.

The irony is that this growth came at a time when we were warned repeatedly that the corporate sector was shrinking and it’s all the fault of the 1986 tax reform act and those pesky pass-through businesses. Here’s a representative example from the Tax Foundation from 2015:

The U.S. loses about 60,000 corporations per year and has lost about 1 million corporations since the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

Over time, more businesses have structured themselves as “pass-through” entities. This allows profits to be passed through to owners and taxed at individual tax rates that are often lower than the corporate tax rate and eliminates double taxation for shareholders.

More than 60 percent of U.S. business profits are now taxed under the individual income tax code rather than the corporate tax code, which explains why the U.S. collects a relatively small amount of tax revenue from corporations despite having the developed world’s highest corporate tax rate.

Outside of taxation, the traditional corporate form often provides the most efficient business structure for large-scale projects and investments. Excessive corporate taxation and the subsequent decline of the corporate sector artificially limits this important aspect of the economy.

The U.S. should do what the rest of the developed world has done: reduce the corporate tax rate, integrate the corporate and shareholder taxes to avoid double taxation, and limit corporate taxation to profits earned domestically.

Just for the record, in 2015 the top rate on pass-through businesses was higher than the top rate for C corporations, but we digress — If the 1986 tax reform spelled the demise of C corporations, how come the smart money continues to pour into them?

The simple fact is the “decline of the corporate sector” narrative was a myth no matter how you measure it. Corporate tax receipts were 1.4 percent of GDP prior the 1986 tax reform; they were 1.5 percent of GDP prior to the 2017 tax reform. Corporate taxes paid as a percent of total government receipts were 8.2 percent in 1986; they were 9.0 percent in 2017.

So the C verses S dichotomy painted by the Tax Foundation and others is the wrong way to frame the debate over how to best tax businesses. What’s the right way? Here are some thoughts:

- The real balancing act is not between pass-through businesses and C corporations, but between public companies and private ones. The decline in C corporation numbers is dominated by private companies either moving into the pass-through space or being gobbled up by public companies. It’s true the number of public companies listed on the US exchanges shrunk by half over the last two decades, but it’s only a few thousand companies and the overall growth of the remaining market cap indicates that what we’re seeing is consolidation, not decline.

- The dramatic increase tax exempt shareholders is likely responsible for some of this growth. In the 1960s, four out of five C corporation shareholders was fully taxable. Today, it’s just one out of four. This growth in tax exempt or advantaged investment increased the pool of capital available to public companies over the past fifty years even as it sharply reduced their effective tax rates.

- The rise of tax exempt shareholders has also given public companies a significant advantage over private C corporations. Unlike public companies, private companies are largely limited to rewarding their shareholders by paying dividends, and those dividends are usually – and in the case of S corporations, always – paid to shareholders who actually pay taxes. The double tax lies more heavily on private companies.

- Tax reform will push more business income into the double tax. Barro-Furman estimate 19 percent of pass-through income will migrate into the lower, 21-percent corporate rate. Wharton estimates its 18 percent. Some of this shift may come from conversions of existing companies, but much of it will be in the form of increased consolidation, either through acquisitions (Berkshire Hathaway) or by public companies taking market share from existing private businesses (Amazon). Bottom line: More business income will be subject to the harmful, distortive double tax in coming years.

The common perception that the 1986 tax reform favored pass-through businesses ignores just how tax-disadvantaged pass-through businesses were prior to 1986. The top tax rate imposed on pass-through income was 70 percent prior to the Reagan revolution. The top rate on C corporations was 46 percent. As result, nearly all business income prior to 1986 was reported by C corporations, not pass-throughs.

But pass-through taxation is the correct way to tax business income! The tax code should tax all business income once, when it is earned, and at reasonable rates. S corporations for everybody is our mantra. Re-read the policy prescriptions of the Tax Foundation paper:

The U.S. should do what the rest of the developed world has done: reduce the corporate tax rate, integrate the corporate and shareholder taxes to avoid double taxation, and limit corporate taxation to profits earned domestically.

We agree – double taxation is the wrong way to tax business income, and eliminating it should be the focus of tax policy moving forward, not promoting myths about corporate-tax-base erosion.