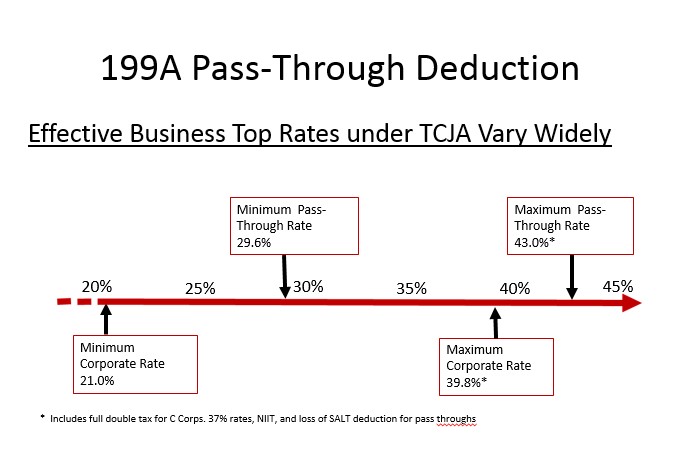

A new presentation on the Section 199A deduction from the Joint Committee on Taxation has gotten people’s attention, particularly this slide:

The slide prompted Senator Ron Wyden, the Ranking Member on the Senate Finance Committee, to observe, “These are not the struggling small business owners we were told this provision would benefit.”

The Ranking Member’s response is misdirected, however. The 199A deduction was not an effort to reduce taxes on small businesses, but rather an attempt to maintain tax parity for pass-through businesses of all sizes. Without 199A, Main Street businesses would face sharply higher tax rates than the C corporations they compete with.

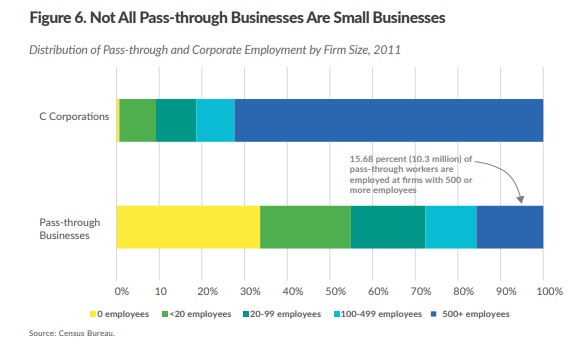

This is well-trod ground, but with the renewed focus on 199A it deserves to be reviewed. Pass-through businesses come in all shapes and sizes, and while on average they are significantly smaller than the typical C corporation, there are some very large pass-through businesses. (Tax Foundation Chart)

Pass-through businesses of all sizes employ the majority of private sector workers – 66 million workers or 55 percent of the total private sector workforce according to a 2015 report from the Tax Foundation. Large pass-through businesses (those with 100 or more workers) employ 18 million of those workers. (Tax Foundation Chart)

These businesses pay a high level of tax, often more than their C corporation competition. You wouldn’t know this from most reporting on pass-throughs. Critics of the sector like to remind us that businesses organized as S corporations, partnerships, and sole proprietorships “avoid” the corporate tax.

This is true, but it is just as accurate that C corporations “avoid” the individual tax. Now that the top individual rate is nearly twice the corporate rate, that is the more cogent point. Why is paying 21 percent tax “fair” but paying 37 percent (29.6 percent with the 199A deduction) is “tax avoidance?”

Faced with this new reality, pass-through critics immediately cry, “Double tax, double tax!” C corporation income is subject to two layers of tax, the corporate layer and then a second layer imposed on dividends and capital gains. A dollar of C corporation income paid out immediately to taxable shareholders faces an effective rate equal to 39.8 percent, not 21 percent. (S-Corp has long supported eliminating this double tax. “S corps for everyone” is our mantra.)

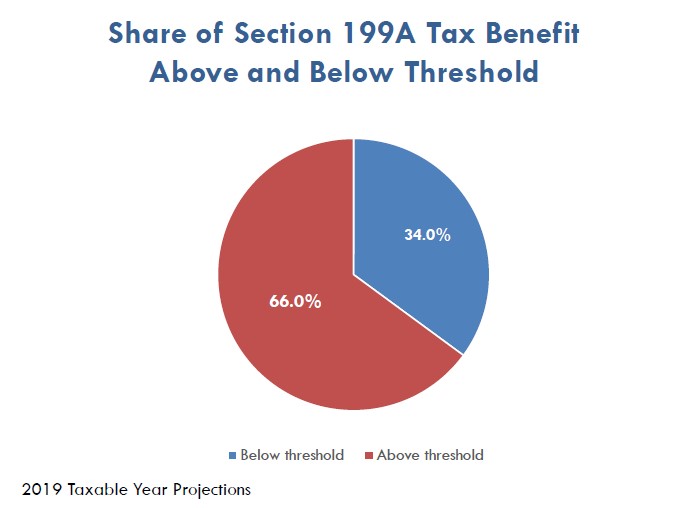

But most C corporations don’t pay dividends, and most dividends (and capital gains) avoid tax. On the other hand, one-third of pass-through businesses don’t qualify for the 199A deduction, while the rest see their tax burden increased depending on their size, location, industry, and ownership. The result is a remarkably broad range of marginal tax rates that apply both to C corporations and pass-through businesses, all specific to the facts and circumstances of each business.

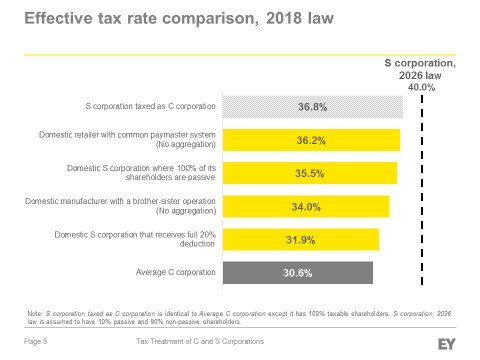

So where does that leave us on parity? Last summer, we asked EY to calculate the effective marginal tax rate of the typical public C corporation under tax reform and compare that rate to the top rates S corporations pay under various circumstances.

As you can see, the typical S corporation with the full 199A deduction achieves an effective rate that is close to the C corporation rate when considering the double corporate tax. On the other hand, those S corporations excluded from the deduction, or only receiving a partial deduction, pay effective rates significantly higher.

An important finding from EY is that conversion isn’t really an option. Companies that convert from S to C would still face higher marginal rates. This is because unlike C corporations, S corporation shareholders are subject to the full second layer of tax. Meanwhile, as closely-held businesses, newly minted C corporations will have to distribute a larger share of their earnings to shareholders to compensate them for their ownership. There is no public exchange for closely-held business stock.

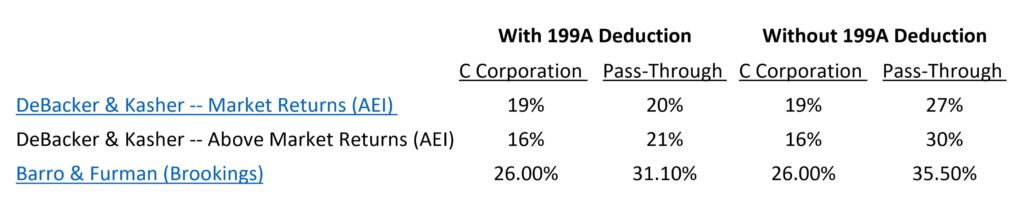

EY’s findings are consistent with the findings of other economists. While the assumptions and numbers vary, the overall message is clear – pass-through businesses that get the 199A deduction pay top tax rates in the same range as their C corporation competition. Those that don’t get the deduction pay rates significantly higher.

The bottom line is that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act achieved rough parity of top tax rates for C corporations and pass-through businesses, but only for those businesses that get the full 199A deduction. If Congress were to repeal Section 199A, or limit it to smaller businesses, that would sharply raise taxes on large pass-through businesses, putting them at a disadvantage and endangering the jobs of 18 million Americans.