Carol Roth Pushes CTA Database Purge

Carol Roth’s latest column in The Blaze makes a powerful case for finishing the job on the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA): both repealing the law outright and purging the massive database of sensitive ownership information the government never should have collected.

As Roth writes:

The Trump administration has made Main Street a central priority — and limiting the reach of the Corporate Transparency Act’s Beneficial Ownership Information rule was one of its best decisions so far. The rule required small businesses to hand over sensitive ownership data to the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, under threat of heavy fines and criminal penalties. Large corporations were mostly exempt.

After small-business owners and pro-business lawmakers protested, the administration moved quickly. In March, it issued an interim rule exempting U.S. small businesses and citizens from the reporting mandate. Treasury then opened a public comment period to shape a final rule. That comment window closed five months ago, and yet the final rule still hasn’t arrived.

Small-business owners want the exemption locked in for good — not left vulnerable to reversal by a future administration. Ohio Republican Rep. Warren Davidson’s Repealing Big Brother Overreach Act, with nearly 200 co-sponsors, aims to make that exemption permanent. But some lawmakers say they can’t codify until Treasury finalizes the rule. The delay is holding back certainty for millions of entrepreneurs.

Many of those same business owners also want FinCEN to purge the personal data they already submitted before the exemption took effect. With hacking and misuse always possible, they’re demanding the government delete the information it never should have collected.

Getting Rep. Warren Davidson’s Repealing Big Brother Overreach Act enacted is a priority for the Main Street business community. So is purging the database.

More than 16 million small businesses filed their beneficial ownership information with FinCEN before the interim rule took effect. That sensitive personal data (names, addresses, identification numbers) remains on government servers, vulnerable to misuse and cyberattacks.

FinCEN Director Andrea Gacki acknowledged this concern, testifying that the agency intends “to resolve questions around the data that we have collected and dispose of data that is no longer legally required.”

That’s a welcome sign, but it would be nice to see some urgency attached to it. Formalizing the new, more limited CTA rules, purging the FinCEN database, and ultimately repealing the CTA are all commonsense actions the Trump Administration can take now to help Main Street businesses succeed under their watch.

Talking Taxes in a Truck Episode 45: Piper Sandler’s Don Schneider on OB3’s Big Refunds

S-Corp highlighted a recent report by economist Don Schneider quantifying the tax relief millions Americans can expect in the next year as a result of the OB3. It’s a big number, so we invited Don, the Deputy Head of US policy at Piper Sandler, to explain why this could be the biggest refund season ever. Don also reviews the future of tariffs (and why they’re likely here to stay even if courts weigh in) and shares his thoughts on why the government shutdown might end in early November.

This episode of the Talking Taxes in a Truck podcast was recorded on October 21, 2025.

IRS Audits and Pass-Throughs

Tax Notes ran an article this morning on the status of the 2-year-old IRS exam unit dedicated to passthrough entities. Spoiler alert – with all the chaos over funding, leaks, investigations, and government shutdowns, it hasn’t got its footing yet. Here’s Tax Notes:

Initially unveiled in September 2023 as part of a broader compliance initiative focusing on wealthy taxpayers, the LB&I exam unit is responsible for starting all exams of passthroughs — partnerships, S corporations, and trusts — regardless of the entity’s size. The unit is supposed to help streamline workflows and boost the agency’s audit coverage of partnerships — entities that have exploded in size, number, and complexity in recent decades but mostly escaped IRS scrutiny because of the agency’s resource constraints and inefficient audit rules.

The Tax Notes story is well written, but glosses over the real headline here – all this focus on audits and enforcement is unlikely to raise new revenues and it ignores the underlying strength of our Tax Code: the willingness of taxpayers to comply.

Here’s how we handled this issue two years ago. It’s held up pretty well:

IRS Ramps Up

Doug Holtz-Eakin has a thoughtful blog post this week on the deterioration of our “voluntary” compliance tax system.

Whenever the term “voluntary” is used when discussing taxes, the tendency is for the audience to bust out laughing. Okay, sure, but it’s a real concept that used to be the heart of our tax system. Rather than send tax collectors door-to-door to make collections, our system relied on taxpayers calculating their own liability and then sending in the appropriate amount.

It was fairly unique in the world yet, as Doug points out, our compliance rate consistently ranks at the top at a solid 85 percent. But as Doug observes, in recent years we have moved away from that successful model:

I used to be proud of the U.S. income tax system. It was founded on the notion of voluntary compliance and stood in stark contrast to privacy-piercing, intrusive systems around the globe. But a system of voluntary compliance relies on the broad trust that everyone is paying the taxes that are due. Over time, that trust has seemingly eroded and the U.S. system relies increasingly on “information” reports in which someone tells the IRS about someone else who earned income. The United States is now a tax nation with sub-kindergarten-level ethical norms.

As evidence of this deterioration, Doug mentions the ProPublica leaks and their attempt to paint a picture of systematic tax evasion, without ever identifying any actual evasion.

From our perspective, Doug could have just as easily pointed to the on-going fight over IRS funding. They say truth is the first casualty of war. Apparently, it also suffers when IRS funding is being discussed. Below is a summary of the recent IRS enforcement related news. Grab some popcorn, ‘cause there’s lots of it.

How Many Agents?

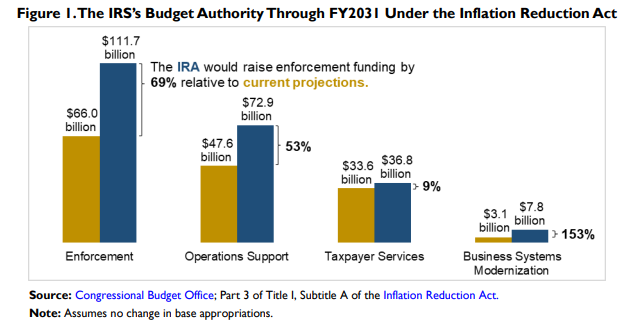

Last year’s Inflation Reduction Act included $80 billion in new funding for the IRS. The table below shows how the funds are allocated:

More than half of the new funding is earmarked for “enforcement,” which makes sense given that the funding boost was largely premised on bringing in tax revenue that would otherwise go uncollected. A document released by Treasury last year projected the new funding would enable the IRS to hire an additional 87,000 employees by 2031, with most of those new hires working on enforcement.

Republicans zeroed in on the estimate and warned taxpayers to expect to face an “army of auditors.” The media furiously scrambled to refute the claims. We were told the “87,000 agent” claim was “absolutely false”, the new hires were mostly to replace departing staff, and the funding would improve customer service and enable the agency to modernize its infrastructure. It was all very warm and fuzzy (see here, here, and here).

In response to its critics, the agency stated the net increase in its workforce would land in the 25- to 30-percent range and that the bulk of new hires would simply replace retiring ones. The IRS employed 79,000 workers in the 2022 fiscal year, so a 25-percent increase would mean 20,000 new employees. Subtract that from the 87,000 planned hires and you’re left with 67,000 new hires filling existing roles. Will the IRS really need to replace 85 percent of its current workforce in the next decade?

IRA Already Producing Results?

More confusion. Forbes reported in August that IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel credited the new funding as helping the agency boost its employment rolls in short order:

Werfel said, by using the IRA funding, the IRS has made an immediate, meaningful difference in how it serves taxpayers, including hiring new employees. While admitting hiring challenges, including ensuring that hiring keeps pace with attrition, Werfel estimates that the IRS is approaching 90,000 FTE. [Emphasis added]

Wow, that was fast. But wait, didn’t this hiring binge begin prior to the Inflation Reduction Act? Here’s a 2022 Washington Post article from before the funding was enacted:

The Internal Revenue Service plans to hire 10,000 employees in a push to cut into its backlog of tens of millions of tax returns by recruiting for jobs across the agency that have gone unfilled for years, according to four people familiar with the plan. The agency will accelerate recruiting in the coming weeks for 80 distinct positions, from entry-level clerical workers to advanced engineers and tax attorneys, one person familiar with the plan said. [Emphasis added]

We were told the decline in IRS staffing was due to a lack of funds – hence the $80 billion in IRA funding. Exactly how was the IRS planning to hire 10,000 additional employees back in March of 2022 if they didn’t have the funding?

The confusion extends to tax enforcement. Reasonable people believe it will take years for new hires funded by the Inflation Reduction Act to have an impact. It takes time, after all, to find the right candidates and more time to get them trained. Not so, says the IRS! Just one year in and we are told it’s already paying off:

IRS Ramps Up Tax Enforcement for Millionaires: IRS tax enforcement led to the collection of $38 million from tax-evading millionaires. But the agency isn’t done making the wealthy pay up.

Exactly where did this windfall come from?

The IRS allocated some of its funding from the Inflation Reduction Act to tax enforcement, and tax-evading millionaires and billionaires are targets. The agency has already closed approximately 175 delinquent tax cases, resulting in a $38 million payday for the U.S. government. With billions of dollars of potential IRS funding on the line (some of which Republican lawmakers have clawed back), the agency is motivated to continue tax collection efforts against the wealthy, and the IRS is nowhere near done.

Targeting “tax-evading millionaires and billionaires” sounds impressive, but $38 million is a drop in the bucket. Moreover, it’s not clear when these cases were opened and if the new IRA funding in fact played a role.

More Enforcement, Fewer Collections

Under the heading of “you can’t make this stuff up,” at the same time the IRS was plugging its new enforcement efforts the GAO was reviewing the agency’s audits of large partnerships. They audited 54 large partnerships in 2019 and (if we are reading this correctly) lost money doing so. Here’s the GAO:

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audits few large partnerships—54 in tax year 2019—and the audit rate has declined since 2007. More than 80 percent of the audits resulted in no change to the return on average from tax years 2010 to 2018, double the rate of large corporate audits. For those that did change, the average adjustment was negative $264,000. [Emphasis added]

Reminds us of the old joke about the entrepreneur who was losing money on every sale but planned to make it up through volume.

Here’s a question: If the IRS loses money targeting just a handful of large partnerships, how are they going to collect an additional $200 billion through expanded enforcement? The answer, apparently, is to do more of the same. You know, volume. Last month, the IRS unveiled a new “special pass-through” compliance arm that will focus on large and complex entities, along with the staffing of 3,700 new enforcement agents. According to the Commish:

“This is another part of our effort to ensure the IRS holds the nation’s wealthiest filers accountable to pay the full amount of what they owe,” said IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel. “We are honing-in on areas where we believe non-compliance among our wealthiest filers has proliferated over the last decade of IRS budget cuts, and pass-throughs are high on our list of concerns. This new unit will leverage Inflation Reduction Act funding to disrupt efforts by certain large partnerships to use pass-throughs to intentionally shield income to avoid paying the taxes they owe.

Somebody should send Commissioner Werfel a copy of the GAO report.

Conclusion

Which brings us back to Doug’s blog post and the future of tax enforcement. Doug ends his post with a call for tax reform that restores our former, less intrusive approach:

The upshot is that the voluntary compliance regime is in tatters. It strikes me that one of the primary goals of any new, broad-based tax law should be to put in place a system that supports the return to a less police-state approach to tax collection. That’s an ambitious goal, particularly for a Congress that cannot yet gavel itself into session with any reliability, but a noble one nonetheless.

We agree.

In the meantime, what can Main Street expect from an IRS that’s flush with cash and has a mandate to bring in billions of new tax dollars? As we explained in an earlier post, all signs point to more audits across the board – despite pledges to steer clear of those earning less than $400,000 – and more press releases from the IRS. Given what we already know about collection rates and the so-called tax gap, it’s unlikely these enforcement efforts will hit their intended goal, but that won’t stop them from trying.

The Big Winners in OB3

For the Main Street business community, the benefits of the One Big Beautiful Bill (OB3) are clear – the bill kept our tax rates low, made permanent the 20-percent small business deduction, and retained full deductions for the state and local taxes we pay on our pass-through business income.

Cumulatively, these provisions will save pass-through business owners more than $100 billion a year. That’s real money they can invest right now in new equipment, new workers, and higher wages.

The case for family tax relief in OB3 is just as strong. As we’ve noted, provisions benefitting middle-income families – including the higher standard deduction, bigger child credit, and lower rates – represent a majority of the tax relief in OB3. When you add in revenue offsets that exclusively target upper-income taxpayers and, well, forget about it. Middle-income families were the big winners here.

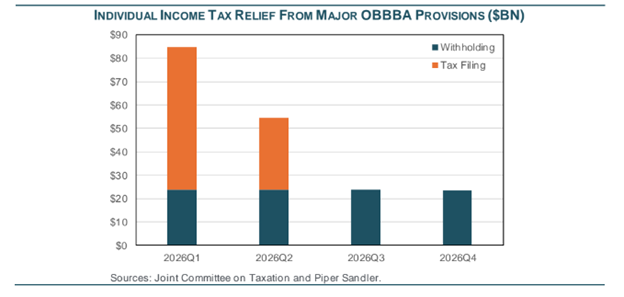

And the news just gets better, as all this tax relief is coming sooner rather than later. As noted by our friends at Piper Sandler, many of these family-friendly provisions are retroactive to the beginning of 2025, meaning the relief starts as soon as they file their taxes next year.

Here’s what it looks like on a chart:

And here’s the key graf:

The recent budget reconciliation bill… could deliver around $191 billion in net new individual income tax relief in calendar year 2026 (0.6% of GDP). Almost half of that relief is retroactive but it seems unlikely many people will adjust their withholding to claim benefits this year. Instead, they will be surprised by large refunds during the filing season next year. During the January to April filing season, we estimate tax filers will receive about $91 billion in additional refunds from the 2025 retroactive tax cuts plus another $30 or so billion from reduced withholding on 2026 taxes. The retroactive tax cuts could average about $1,000 per return though it will be substantially more for some filers.

So families and Main Street businesses were the big winners in OB3. That’s not what the DC media will tell you, but then we stopped listening to them a long time ago.

Australian CbC Reporting and S-Corps, Continued

The S Corporation Association today sent a letter to the Australian Tax Office (ATO) building on our ongoing discussions regarding how Australia’s proposed Country-by-Country (CbC) reporting rules could affect S corporations operating in the United States.

By way of background, Australia is in the process of implementing new CbC reporting requirements they say will provide greater transparency for multinational companies doing business in the country. These rules would apply to sizable companies doing business in Australia, including large S corporations.

S corporations are pass-through entities, however, taxed at the shareholder rather than the entity level, and therefore do not pay corporate income taxes or maintain entity-level tax information that the Australian rules are designed to capture.

As the letter notes:

Subjecting S corporations to the CbC reporting would fail to produce the information the rules are designed to collect – namely, whether large businesses operating in Australia are appropriately contributing to Australia’s tax base. Instead, the reporting would provide a distorted view of tax compliance by reporting income but no tax payments, while also raising significant shareholder privacy concerns.

S-Corp isn’t alone in raising concerns. Other companies have voiced similar warnings about the unintended consequences of Australia’s approach, citing both competitive and privacy risks. Together, these comments underscore the debate over CbC reporting is not about opposing transparency; instead, it’s about ensuring such efforts are designed to collect meaningful, accurate information without undermining legitimate privacy protections.

The letter also highlights the structural safeguards embedded in U.S. law that prevent S corporations from being used as vehicles for tax avoidance. Only individuals (not corporations or partnerships) can own S corporation shares while ownership is subject to a single class of stock rule that ensures all shareholders are treated proportionally. As the letter points out, “these unique rules ensure that, should the ATO grant an exemption for S corporations from the CbC reporting regime, it would not open the door to avoidance strategies.”

To address these concerns, the ATO should exempt S corporations from the CbC requirements entirely. At a minimum, they should limit reporting to business operations within Australia only. Such a targeted approach would avoid the misperception that S corporations pay no tax and protect shareholder privacy, while providing Australian authorities with meaningful information on income and activity within their jurisdiction.

We’ll continue working with Australian tax officials and other international stakeholders to ensure that S corporations are treated appropriately under foreign transparency regimes.