The Tax Foundation is out with a new write-up called, “Are Pass-Through Businesses Treated Fairly Under the Senate Version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act?” that has a chart showing the top rate applying to S corporations in the Senate bill is 34.94 percent while the C corporation rate is 39.04 percent. Is that correct? No. Not even close.

Here are the concerns we have with the Tax Foundation Write-Up:

Deferral: The Tax Foundation analysis assumes that the full second layer of corporate tax is paid, and paid immediately. This is simply not true. First, there are some taxpayers who will never pay that second tax, such as tax-exempt organizations and estate beneficiaries entitled to stepped-up basis. Second, foreign shareholders are often subject to much more favorable treaty rates. Third, shares held by qualified plans can put off any tax liability for years, if not indefinitely. Finally, earnings retained inside the C corporation might not be subject to tax for years. The time value of money makes a big difference when only one category of taxpayers gets the benefit of it.

The result of these exceptions is that the second layer of tax has a very low effective rate. A recent (badly flawed, in our view) study authored by several Treasury economists estimated the second layer added 8.9-percentage points to the corporate effective tax rate, but that appears high. You can read our concerns with this study here and here. A more recent CRS analysis determined that the actual effective rate for the second layer of tax was just 2.3-percentage points. Split the difference, and you’re around six-percentage points. Or about ten points less than the pass-through penalty in the Senate bill.

The 17.4 Percent Deduction: The Tax Foundation acknowledges that the 17.4 percent deduction is limited to 50 percent of payroll and would not be available to all S corporations, but it makes no attempt to quantify the impact that limitation would have on marginal rates. The reality is that many businesses with significant levels of capital and payroll will get a deduction well below 17.4 percent, which means their top rate will be higher. Professional service S corporations above the $500,000 income threshold get no deduction at all. Add in the effects from the loss of SALT and their top tax rate is around 47 percent in the Senate bill, not 34.94.

State and Local Income Tax Deduction: The Tax Foundation ignores the effects of repealing the SALT income tax deduction for S corporations while preserving it for C corporations. Preventing businesses from deducting this business expense could raise marginal rates on S corporations significantly, depending on which state they reside in. Those in Wyoming, for example, would see no effect, while those doing business in California would see their marginal rates increased by five-percentage points. On average, SALT repeal raises effective marginal rates by between two- and three-percentage points.

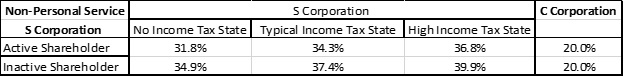

To give you an idea of just how far off the Tax Foundation is in asserting money a single top pass-through rate of 34.94 percent, here is our chart with a more comprehensive and accurate range of possible rates for non-personal services corporations who qualify for the full deduction. Corporations who do not qualify for the full deduction would obviously pay even higher rates:

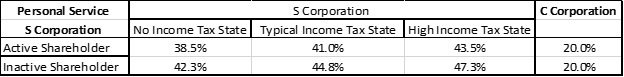

For personal services corporations, the range of possible outcomes is even higher:

Finally, there has been a renewed chorus out there of “they can just convert!” This response ignores the reality of pass-through taxation as well as the history of the S corporation and why Congress embraced the pass-through model in the first place.

Think about it this way: Two identical companies compete; the only difference between them is their ownership structure – one is a family-owned and closely-held S corporation, while the other is a public C corporation; otherwise, they make the same product, the employ the same people, and earn the same before-tax profits.

C Corporation under the Senate Bill: The C corporation under the Senate bill pays just 20 cents of tax on every dollar it makes. It could pay out the remaining 80 cents in dividends, but like many C corporations, it chooses not to, retaining the earnings within the corporate structure instead.

This has the effect of driving up its share prices and shareholders who need money can sell their shares on the public markets. This is a very efficient way to reward shareholders. It drains no capital from the company, the additional tax is shouldered by the shareholder, and the shareholder, not the company, chooses when to sell the stock. Meanwhile, the company has the ability to retain the full 80 cents of after-tax profits.

S Corporation under the Senate Bill: As an S corporation, the family business will pay a much higher initial layer of tax under the Senate bill. Assuming this business 1) gets the full 17.4 percent deduction, 2) has a mix of active and inactive owners, and 3) is in a median tax state, it will need to pay out tax distributions of around 38 cents for every dollar it earns, nearly twice the tax applied to the C corporation. These distributions would cover the federal tax owed by the shareholders, and they need to be paid every quarter, just like C corporation taxes. Depending on the applicable base broadening, the tax owed by this S corporation may be larger than the tax owed under current law. (Many S-Corp members report a tax hike under the Senate bill.)

So, the S corporation is only able to retain about 62 cents of every dollar it makes, compared to the 80 cents retained by the C corporation. Over time, the disparity will allow the C corporation to accrue substantially more capital than the S corporation, giving it an advantage when competing over projects, strategic purchases, etc.

And what about rewarding shareholders? There are no public markets for S corporation stock, so selling a minority stake in the business is not really an option. Instead, the S corporation would need to make additional distributions. These would drain additional revenue from the company, further increasing the advantage of the C corporation.

Converted S Corporation: Finally, the S corporation could convert to access the lower 20 percent rate. Since its ownership structure is closely-held, however, it would need to continue to pay out dividends to reward its shareholders, as there is no ready market for minority stakes in a family business even when organized as a C corporation.

Moreover, the company was recently an S corporation, so all its shareholders are likely taxable, meaning the full double tax would still apply to them. The result is largely the same as if the business elected to remain an S corporation. The effective tax is in the high thirties, and the only way to reward shareholders is to pay out dividends, draining additional resources from the company.

The challenge presented to S corporations by the Senate bill is exactly the reason why Congress created the S corporation back in 1958. Public C corporations have many advantages over private companies, and those advantages will be exacerbated by the Senate bill. Unless it is amended, the Senate bill will force many S corporations to make the difficult, and by no means costless, transition to C corporation status. But they won’t be better off, and they will have to change how they operate. None of this is good for investment or job creation, which was supposed to be the point of tax reform in the first place.