Marty Sullivan has an interesting post in Forbes this week on the pass through rate challenge, arguing that S corporation shareholders who don’t want to see their taxes go up are being greedy. He says:

You see, for international competitiveness reasons, tax reform must lower corporate rates, and the traditional way to pay for a corporate rate cut is to rid the code of business tax breaks. But if business tax credits and deductions are repealed, they’ll be stripped from passthroughs as well. Passthrough taxes will be raised to pay for tax relief for multinationals. God forbid, Congress raise taxes on “small business.” Even though logic and many estimates indicate this would not be unfair because passthroughs are subject to only one layer of tax unlike double–taxed corporations, it would be political suicide for Congress. We put “small business” in quotes because many passthrough businesses are big law firms, accounting firms, and manufacturing businesses (like Koch Industries).

Yes, God forbid that, as part of a reform effort to make US businesses more competitive, Congress avoid raising taxes on the businesses that employ most workers. What an odd place tax experts, like Marty, reside in, where cutting rates on large multinationals is absolutely essential, but a similar reduction in rates for locally owned employers is a sop to the rich. If his proposed solution of wage credits is such a great idea, apply them to C corporations too.

The simple fact is we have argued for years that tax reform should level out the top tax rate for all forms of income while also eliminating the corporate double tax. More than 100 trade groups signed on to that approach in 2016. It would lead to both fairness and simplicity, while dramatically reducing the cost of investing in the US, which is the ultimate goal.

But that reform is not on the table, partly due to the opposition of Marty and the elected officials who listen to him. We’re on to a plan that’s not perfect, but at least it moves in the right direction, reducing rates on employers while reducing the effects of the harmful double corporate tax.

Meanwhile, opposition to the idea of a lower, pass through rate is predicated on a large number of fallacies that need to be addressed. Marty begins his piece by assuming that C corporations pay higher taxes. Really? After all his work highlighting how companies like Apple use overseas tax havens to reduce their US tax burden, he hasn’t made the connection that it is domestic businesses like S corporations that pay the highest rates?

Below are the fallacies that have been raised in recent months and our response. We hope it is helpful.

Fallacy: Pass through business pay lower tax rates.

Response: Not true – pass through businesses pay higher initial top rates than C corporations – 44.6 percent v. 35 percent. While C corporations are subject to a second layer of tax on their dividends and capital gains, the vast majority of C corporations do not pay dividends and most C corporation shareholders do not pay taxes – they are tax exempt charities and foundations, or qualified retirement plans and foreigners.

The result is that S corporations, not C corporations, pay the highest rates. Effective tax rates according to our 2013 study include:

- Sole Prop: 15%

- C corps: 27%

- Partnerships: 29%

- S Corporations: 32%

Fallacy: Pass through businesses are “tax favored.”

Response: Critics argue that “S corporation owners choose that form so it must be to their advantage.” The same observation applies to C corporations, however “C corporation owners choose that form so it must be to their advantage.” What are the advantages of being a C corporation?

- Lower Rates: C corporations are taxed at lower top rates than S corporations – 35 percent verses more than 40 percent.

- Tax Exempt Shareholders: Unlike S corporations, C corporations can have tax exempt shareholders and many do. According to the Tax Policy Center, 75 percent of C corporation shareholders are tax exempt or tax advantaged.

- Deferral of Tax on Overseas Income: C corporations can indefinitely defer repatriating income from their overseas operations to avoid the US tax. S corporations, on the other hand, would have to sacrifice their foreign tax credits if they defer, so it isn’t an effective strategy for them.

- Base Erosion Practices: C corporations can shift income overseas to avoid high US tax rates. For S corporations, no deferral means no income shifting.

- Less Aggressive AMT: There is a Corporate Alternative Minimum tax, but it is not as aggressive as the Individual AMT that applies to S corporations. The fact is most successful S corporation shareholders pay the AMT, not the regular tax code.

Fallacy: S corporations are dominated by professional service sector companies.

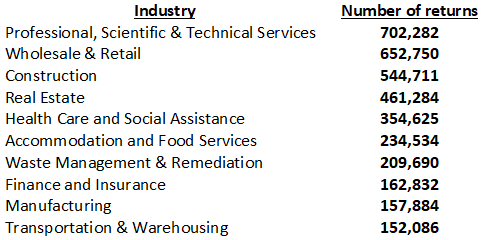

Response: Wrong – the S corporation community is so large, it looks very much like the economy as a whole, and includes an extremely diverse population of businesses. Of the 4.2 million active S corporations, there are lots of service sector S corporations, but there are also lots of S corporations in retail, wholesale, manufacturing, construction, arts, information, finance, etc. Here’s a list of the industries with the most S corporations:

Fallacy: Large pass through businesses don’t employ that many people.

Response: The opposite is true – large pass through businesses are a significant source of jobs. Our 2011 EY study found that most private sector employees (54 percent) work at pass through businesses; one in four works at an S corporation; and nearly one in six (20 million) works at a large pass through with more than 100 employees. The Tax Foundation does an annual review of the pass through sector, including a description of their size and employment practices. According to their 2015 report, pass through businesses with more than 500 employees account for more than 10 million jobs.

Fallacy: The new pass through rate will only benefit the rich and not help real businesses with real employees.

Response: Not true. According to a 2011 Treasury report on small businesses, two-thirds of the income earned by pass through employers is subject to the top tax rates. Reducing this rate would give these employers more resources to hire and invest, exactly what tax reform is designed to do.

Fallacy: The new pass through rate will reduce payroll taxes.

Response: Properly constructed, the new pass through rate will apply to real profits from real businesses and will protect against taxpayers seeking to make their wages look like profits. The pass through community is working with tax writers to ensure these rules are effective and robust and that the value of the lower rate is reserved for real business profits only.

Fallacy: The Framework is a repeat of the Kansas experiment.

Response: Not true. Kansas offered pass through businesses a tax rate of zero on their profits while failing to provide any effective guardrails against cheating. The Framework would subject pass through business profits to a top rate of 25 percent, not zero and five points higher than C corporations, and include stringent rules to ensure that lower rate is reserved for real business profits only. Representative Lynn Jenkins penned an excellent response that raised these points.

Fallacy: The growth of the pass through sector costs the Treasury $100 billion a year in tax revenue.

Response: This statistic is from a 2015 Treasury report that explicitly did not claim pass through businesses cost the federal government $100 billion a year. Treasury said:

We stress that this exercise is not a projection for the likely effects on tax revenue from business tax reform. It is mechanical and assumes no behavioral responses, but has the advantage of being transparent.

Apparently not, since so many publications missed this point. More importantly, many of the assumptions the Treasury study uses to drive its results are simply flawed. The result is the report exaggerates taxes paid by C corporations while minimizing those paid by pass through businesses. You can read more here, here, and here.

Fallacy: S corporations can just convert.

Response: Unlike C corporations, with few exceptions all S corporation shareholders are fully taxable individuals living in the United States, so the burden of the double tax would fall fully on them. Moreover, as closely-held and family-owned businesses, they often have no choice but to pay dividends to their shareholders. So, a tax reform that cuts C corporation rates while leaving pass through rates high would present S corporation with a lose-lose scenario. Remain an S corporation and pay higher taxes, or convert and pay higher taxes. Given that S corporations employ one out of four private sector workers, there is simply no justification for forcing them into this position.