Yesterday 42 Main Street trade groups, including the National Beer Wholesalers Association, the Independent Community Bankers of America, the Associated Builders and Contractors, and the S Corporation Association sent a letter to Chairman Hatch calling for tax reform that treats Main Street businesses fairly. As the letter states:

While the bill’s 17.4 percent deduction is a welcome effort to lower rates on all pass-through businesses, the provision is both temporary and too low. The deduction’s 50-percent payroll limitation would leave behind pass-through businesses that do not add direct payroll at a one-to-one ratio as they grow while blocking trust and estate income from the deduction would hurt multi-generation family businesses. The fraction of pass-through businesses that do get the full deduction would be subject to a 32 percent effective marginal rate, well short of the 25 percent rate forecast in the Framework and significantly higher than the 20 percent rate applied to C corporations.

The disallowance of the State and Local income tax deduction would increase this gap further, raising effective tax rates on pass-through businesses operating in States with income taxes. Meanwhile, the proposed limitation on a businesses’ ability to deduct active pass-through losses would discourage entrepreneurial activity, business formation and investment, as would the exclusion of pass-through businesses from the new, territorial regime on international income.

As a result of these provisions and others, we are concerned that the Senate bill would increase the tax burden on many pass-through businesses relative to current law, while the bill’s rate disparity with C corporations creates a significant competitive disadvantage for many more.

Meanwhile, the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) weighed in with similar concerns, arguing:

The AICPA has long championed parity in the marginal income tax rates between C corporations and pass-through entities. The proposal to create a 17.4% deduction on qualified business income limited to 50% of wages would create a pass-through rate trending to the low- to mid-30% range for many taxpayers. In comparison, a corporate tax rate of 20% would result in a strong incentive for businesses to operate as a corporation as opposed to a pass-through entity. Currently, pass-throughs generate more than 50% of business income reported to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) because their single-tax regime is tax-efficient. Providing an effective rate on pass-throughs at 32% and above will dampen this growth segment of the U.S. economy and push many taxpayers into the corporate double-tax regime.

Pass-throughs are the preferred form of entity for most small and new businesses and the proposed rate disparity would discourage their formation. The Tax Code should not drive taxpayers’ decisions on how to form their businesses. Under the principle of neutrality, it is important to minimize the effect of the tax law on a taxpayer’s decision. Congress should encourage businesses to make decisions motivated by economic and business factors such as interest rates, supply and demand, inflation, technology, and human capital, rather than by tax considerations.

All these groups support comprehensive tax reform that helps all employers compete, regardless of how they are organized. With some adjustments, the Senate draft can be that bill. These letters are designed to identify what adjustments are necessary and to be supportive of those Senators fighting for Main Street businesses.

Potential Tax Hikes in the Senate Bill

After two weeks of consideration, many observers still do not understand how the Senate bill would increase taxes on a large number of family-owned S corporations. For example, one writer recently noted:

Flow through firms get a big tax rate cut under the Senate tax reform bill. The 39.6 percent income tax rate on mature flow through firms is reduced to 31.8 percent in the Senate bill. This, combined with the 3.8 percent SECA/NIIT tax, results in a tax reform rate of about 36 percent on flow through firms.

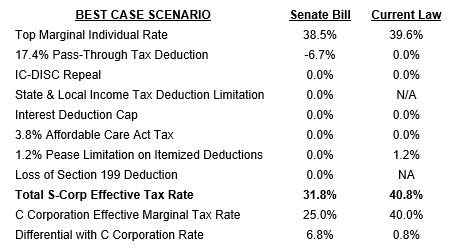

To reach this conclusion, however, this analysis simply ignores many of the provisions in the Senate bill. To make the point clear, here is a breakdown of how the Senate bill would apply to a large family business, starting with the best case scenario. For comparison purposes, we include an effective marginal rate on C corporations that includes the 20 percent rate in the Senate bill, a five-percentage point effective marginal rate for the second layer of tax, and any applicable base broadening. We do not include any benefit from the bill’s expensing provision – such a benefit would apply to C and S corporations alike, is wholly dependent on specific facts and circumstances, is a timing benefit only, would be mitigated by the loss limitation provisions in the bill, would not benefit mature companies with consistent levels of capital expenditure, etc. In other words, its effects are simply too complicated to generalize.

Best Case: The headline benefit for S corporations in the Senate bill is a 17.4 percent deduction applied against qualified pass-through income. That deduction is not available to personal services businesses and its size can be no more than 50 percent of the businesses W-2 wages paid to employees (not owners). The deduction also doesn’t apply to shares of an S corporation held by an EBST, an estate, or other type of trust. Finally, the Senate bill does not repeal the Obamacare taxes, so inactive shareholders of an S corporation would have to pay the additional 3.8 percent tax. Under the single class of stock rule, that tax would have the effect of increasing tax distributions for active and inactive shareholders alike.

On the base broadening side of things, the Senate bill would eliminate the Section 199 deduction, cap interest deductions, repeal the IC-DISC, and disallow deductions for most state and local income taxes. (The bill includes many other base broadening provisions, including a new loss limitation rule that raises more than $100 billion on pass-through businesses, but this analysis focuses on just those four.)

So with all that in mind, the best case scenario under the Senate bill would be where the business:

- Has active owners only;

- Is not a personal services business;

- Is not eligible for Section 199;

- Has no trust ownership;

- Resides in a no-income-tax state;

- Has low levels of interest expenses; and

- Has no export income.

Here’s the resulting effective marginal rate:

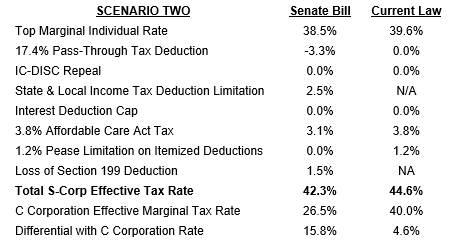

Has a mix of active and inactive owners;Compared to current law, this S corporation is considerably better off, with an effective marginal rate nine-percentage points below current law. That rate is almost seven points higher than the new C corporation rate, but it’s a significant tax reduction nonetheless. That’s the best case scenario, however, and it would apply to a small percentage of family-owned S corporations. What would happen with a more likely set of facts where the business:

- Is not a personal services business;

- Is eligible for Section 199;

- Has 50 percent trust ownership;

- Resides in an average income tax state;

- Has low levels of interest expenses; and

- Has no export income?

Here is the resulting effective marginal rate calculation:

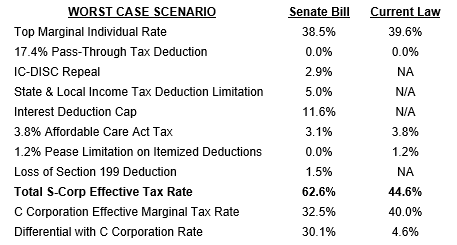

Here is an “even worse” case set of facts where the business:In this case, not only is the S corporation much worse off compared to the C corporation (16.5-percentage points higher), its effective marginal rate is basically unchanged compared to current law. But what about the DISC repeal and the interest deduction cap? The Senate interest cap is much lower than the House version and will affect a significantly larger population of businesses. Moreover, since the marginal rate applied to the interest deduction is higher in the Senate bill for pass-throughs, it will hit them harder than C corporations. And this doesn’t even consider the fact that, given the single class of stock rule, the corporation would have to make tax distributions at the rate of 42.3 percent in order to fully reimburse its shareholder trusts for their additional tax attributable due to the inapplicability of the 17.4 percent deduction to them.

- Has a mix of active and inactive owners;

- Is not a personal services business;

- Is eligible for Section 199;

- Has 50 percent trust ownership;

- Resides in an average income tax state;

- Is above the interest cap by ten percent of income; and

- Has 20 percent export income

Here is the resulting effective marginal rate calculation:

Finally, we did a “Best Case Scenario” so let’s do a worst case one as well. Move the company to California, increase debt limit excess to 30 percent of income, and increase trust ownership to 100 percent:This scenario demonstrates why the pass-through community is so concerned with the Senate bill. There is simply no way this business can continue as is. It would have to put itself up for sale or convert to C corporation status and change its ownership structure and governance practices to avoid the double corporate tax, just like most existing C corporations do today. Neither option is an improvement over current law and either way the business would be at a competitive disadvantage compared to public C corporations.

This may be a worst case, but there are many S corporations in California and other high tax states with high levels of trust ownership and debt. In other words, this example is reality for many family S corporations today. For S corporation owners, we encourage you to analyze the impact of these proposals on your own tax situation now. This is not a situation where we can afford to wait until after this legislation is passed to “learn what is in it.”