Rate Hikes Still in Play

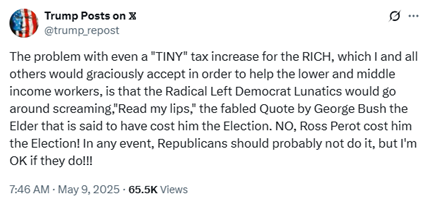

The White House as recently as yesterday was actively pushing lawmakers to include a rate hike in Tuesday’s Ways & Means markup, with Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick telling reporters the rate hike was a “smart” move. Then this morning President Trump appeared to back off the effort, posting the following:

An hour later NEC Director Kevin Hassett appeared on CNBC and when asked about the proposal said the President is “not thrilled about it…it’s not high on the President’s list.”

So it’s anyone’s guess where things stand over at the Administration, but we do know that Main Street remains staunchly opposed to rate hikes. As our trade association letter signed by more than 90 of our allies made clear, the proposal would be devastating for millions of pass-through businesses:

The so-called “millionaire tax” in question…would saddle Main Street with a tax hike that offsets about half the tax benefit of extending the Section 199A deduction. Coupled with the Net Investment Income Tax and state and local taxes, the proposal would impose marginal rates exceeding 40 percent on businesses that receive the full Section 199A deduction, or twice the rate paid by C corporations.

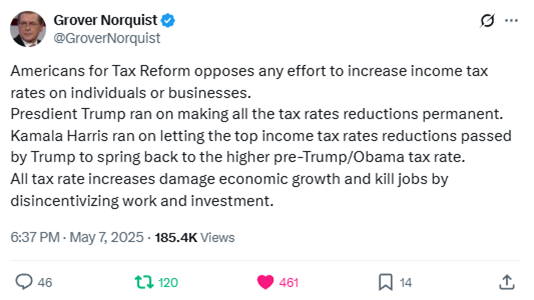

Is there broad support in Congress for tax hikes? Absolutely not. As chronicled by ATR in their latest release – there is simply no way a rate hike passes this Congress.

That said, we’re not taking any chances. S-Corp is reaching out to all lawmakers on Capitol Hill to remind them just how bad this idea is. Our members are already confronted with a shrinking economy, unprecedented tariffs, supply chain disruptions, and a pending fiscal cliff. Tossing a rate hike into the mix is economic malpractice that will cost jobs and slow the economy further.

Main Street businesses need to reach out to their representatives now, and Members of Congress need to make public their opposition to rate hikes.

Main Street (Still) Opposes Rate Hikes

The buzz on K Street is that the White House has resumed its push for Congress to raise the top tax rate as part of the upcoming tax package. If you’re confused by this (possible) development, so are we. Just a couple of weeks ago, the President signaled his opposition to rate hikes. Now they might be back on the table.

While that may be the case, it’s hard to envision a world in which a rate hike can pass either the House or the Senate this year. Most Republicans vigorously oppose such a move, as does Main Street. Our recent letter – signed by 90-plus national trade groups – outlines the challenges:

Pass-throughs comprise over 95 percent of all businesses and employ 62 percent of the nation’s workforce. Most pass-through business income is taxed at the top rates, so raising these rates would harm Main Street businesses engaged in just about every aspect of the economy. They are responsible for employing millions of Americans, driving investment, and supporting local economies nationwide.

The so-called “millionaire tax” in question – which actually kicks in at income around $620,000 – would saddle them with a tax hike that offsets about half the tax benefit of extending the Section 199A deduction. Coupled with the Net Investment Income Tax and state and local taxes, the proposal would impose marginal rates exceeding 40 percent on businesses that receive the full Section 199A deduction, or twice the rate paid by C corporations.

ATR president Grover Norquist understands the danger of higher rates. Here’s what he had to say:

What about increasing 199A to offset the tax hike? That won’t work either:

Certain industries are precluded from Section 199A, however, as is foreign-sourced income and Section 1231 gains. So-called “guardrails” tied to wages, capital investment, and taxable income reduce the value of the deduction for many more. Businesses ineligible for the full 199A deduction would face combined marginal rates above 50 percent. Rates that high are simply not sustainable.

For those businesses who don’t get the full 199A, this plan would simply be another tax hike as the rate hike would apply to ALL pass-through income over the threshold, while 199A only applies to some income.

Finally, a rate hike will not blunt criticism that the pending bill benefits the rich. No matter how high rates get, critics will always claim fairness demands that they be higher.

If this idea does gain traction in Congress, expect to see vigorous opposition from the Main Street community and many members of Congress. With the economy slowing and supply chains in jeopardy, Main Street needs tax relief and certainty right now, not more tax confusion.

Talking Taxes in a Truck Episode 42: Joe Lieber – Bullish on A Tax Deal

Joe Lieber is a founder and co-managing partner of Capitol Policy Partners, a veteran DC insider and a three-time TTT podcast guest! Joe kicks things off with an overview of the tariff debate and where he thinks things are headed, how the bond markets will react, and whether the levies can be rolled into the budget reconciliation package. We then turn to tax policy, where Joe gives his bull case for the massive tax and spending bill and how it will scale numerous hurdles to get to the President’s desk.

This episode of Talking Taxes in a Truck was recorded on April 28, 2025, and runs 38 minutes long.

Business Community Rallies Against B-SALT Proposals

The closer we get to a real tax bill, the louder the opposition to a possible B-SALT cap becomes. That’s a good thing, because the threat is real.

First, an explainer – lots of folks are talking about C-SALT (state and local taxes paid by corporations) deductions these days, but that’s a misnomer. There is no separate corporate policy regarding SALT deductions. If Congress caps C-SALT, it caps deductions for S corporations and other pass-throughs too. It’s the same deduction. So forget about C-SALT and talk about B-SALT instead, because we are all in the same boat here.

On the B-SALT front then, lots of activity. Main Street Employer Coalition members have had literally thousands of members hit the hill in recent weeks, talking up 199A and raising concerns about a possible B-SALT cap. The Texas Oil and Gas Association also followed suit, writing yesterday:

Make no mistake: limiting the B-SALT deduction would punish the very companies that helped build the strongest economy in American history and make achieving President Trump’s Energy Dominance Agenda far more difficult. It would weaken our competitiveness, reduce investment, and ultimately harm the workers and families who depend on a thriving energy sector…Furthermore, economic analysis shows that eliminating the B-SALT deduction would shrink GDP and eliminate over 21,000 full-time equivalent jobs. That’s not progress. That’s a step backward.

Meanwhile, Main Street ally Doug Holtz-Eakin might not have gotten the memo about B-SALT, but he clearly understands the threat the policy poses to the business community. As he noted in a recent post:

CSALT has no relation to SALT. Firms deduct the costs of generating income – wages, rents, capital costs, etc. – and CSALT is the recognition of those costs. Fully deducting those taxes is necessary to correctly measure net income, and thus necessary to correctly tax firms. Capping CSALT is professional malpractice.

Put differently, capping CSALT is simply a tax on the most successful U.S. companies and would threaten jobs, investment, and higher real wages. The debate over the desirability of raising the corporate income tax rate has been settled – it should remain untouched at 21 percent. Capping CSALT is just a corporate rate hike in disguise – roughly the equivalent of raising the rate to 23 percent.

Doug is correct about the marginal rate effect of capping SALT for C corporations. The hit to pass-throughs would be worse, as their top rates are higher so the loss of the deduction would cost them more.

Finally, our friends at the Family Business Coalition just sent this letter up to the Hill, including this paragraph opposing a cap:

FBC fully supports your efforts to permanently extend TCJA and in addition urges you against raising taxes on any US businesses in the process. As an example, recent proposals to limit businesses’ ability to deduct state and local taxes from their federal returns would be a step in the wrong direction with respect to simplifying the tax code and providing tax relief. While the majority of our family businesses are “pass-through” businesses like S-Corps, LLCs, and sole proprietors, we also jointly represent millions of privately owned C-Corporations. Privately owned corporations that do not issue shares to the public far outnumber public companies. Any proposal that rolls back their ability to deduct state and local would dampen the economic benefits of renewing TCJA. The Tax Foundation recently warned that limiting C-SALT will reduce economic output and would effectively amount to a corporate tax rate increase for many private businesses.

So the business community is waking to the threat of capping B-SALT. The point of the tax bill is to preserve the TCJA’s tax relief for families and family-owned businesses. As with the horrible 40-percent rate idea, capping B-SALT would move us in the wrong direction.

Chairman Smith Quashes Tax Hike Rumors

Missouri Congressman Jason Smith, who heads up the tax-writing Ways & Means Committee, was on Mornings with Maria yesterday to talk all things tax policy. The Chairman was asked about a so-called “millionaire tax,” and his response should give comfort to millions of Main Street businesses that would see their taxes increased under the ill-conceived proposal.

Here’s the key excerpt:

What has been discussed by news media – not within Congress but by news media – is that we might increase the top tax rate. What I’ve said all along is that we’re looking at every tax provision – every single provision – and we’re looking at what makes the tax code pro-growth, pro-worker, pro-family.

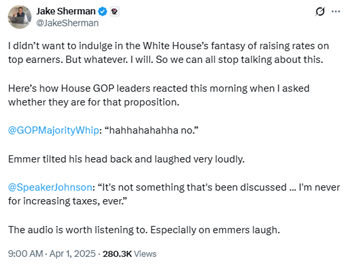

Chairman Smith’s response here mirrors that of other Republicans, including Speaker Johnson and Whip Emmer:

As we’ve discussed before, the proposal aims to raise top marginal tax rates to roughly twice what public C corporations pay. While it’s being labeled a “millionaire’s tax,” the reality is it would primarily impact Main Street businesses, pushing their rates to levels not seen in nearly 40 years.

How did this rumor get started? On Squawk Box earlier this month, CNBC’s Robert Frank revealed that it stems from an offhand comment made by the President. Asked if he’d ever heard President Trump explicitly say he favored letting the top rate go back to 39.6 percent, Frank replied:

No – according to two reports, at a meeting with Republicans [Senator] Lindsay Graham asked, “you said everything’s on the table – would you support raising rates on top earners?” And Trump said, “yeah I’d consider that, I consider everything.”

So the current news cycle is being driven by nothing more than semantics, but as we’ve said before no bad idea ever truly dies in Washington, DC. That’s why S-Corp led a trade association letter last week calling out the proposal, and continues to educate lawmakers on its harmful effects. The “millionaire tax” may be more media hype than legislative reality at the moment, but it’s critical that lawmakers understand who would actually bear the burden of this policy.