The pass through mantra, supported by more than 100 national business trade groups, is simple – tax business income once, tax it when its earned, tax it at the same reasonable top rate, and then leave it alone!

Do you want to stop inversions and keep American corporations here at home? Adopt the mantra. Do you want to make sure Main Street continues to be a source of job creation and economic stability? Adopt the mantra.

We’ve been on this message for five years, and sometimes you get the sense it’s starting to sink in. For example, the Brady blueprint released earlier this year was significantly improved over the Camp draft that preceded it. Tax rates were lowered for pass throughs and C corporations alike, as was the cost of capital investment in the US. That’s a good thing.

And then you have the last week.

First, the Center for American Progress issued a paper labeling pass through taxation a “loophole” and calling for double taxing all US businesses with more than $10 million in revenues. Ouch. Has CAP noticed that our best corporations are fleeing the US just to avoid the double tax? So why would extending its reach to Main Street be a good idea? See our response to the CAP paper below.

And then there’s this:

“We may end many of the loopholes that are currently being used,” Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump said on CNBC in response to question about the use of so-called passthroughs to lower tax rates.

Asked if it’s fair to say he wouldn’t allow passthroughs, Trump said, “We are looking at that very strongly.” More details are coming within two weeks, he said.

Just to be clear, the “loophole” Trump is referring to is different than the “loophole” CAP references. CAP wants its readers to think the pass through structure itself is somehow a loophole because they pay different taxes than C corporations. We address that bogus concern below.

Trump is referring to the challenge of taxing different forms of income at different rates and the opportunity for tax arbitrage that it creates. As Trump advisor Steve Moore told Politico:

Stephen Moore, one of Trump’s economic advisers, made it clear to Bloomberg and to Morning Tax that the campaign is committed to stopping high-earning individuals from gaming that system. But he added: “All I’ve said is that there will be rules, to make sure that the business income that’s declared is actually business income and not wage and salary income in disguise. How you do that is beyond my pay grade. I’m not a tax lawyer.”

Trump suggested to CNBC that his campaign could roll out those rules within two weeks. But Moore told Morning Tax not to hold our breath: “I doubt it. This is a presidential campaign. This isn’t a Ways and Means markup.”

Mr. Moore is exactly right. This issue has been around for a long time and it’s not going to be resolved in the next two weeks. It’s also a reminder that the best tax reform would restore rate parity to all forms of income – individual, corporate, and pass through alike. Anytime you tax different forms of active income at different rates, you run the risk of arbitrage.

That’s why the Pass-Through Principles letter says, “To ensure that tax reform results in a simpler, fairer and more competitive tax code, Congress needs to reduce the top tax rates to similar levels for all taxpayers.”

Of course, CAP and its allies oppose lowering individual rates, which has created the problem in the first place. How do you make US businesses more competitive without lowering tax rates on individuals? It’s not easy, but we know one thing for certain – you don’t make them more competitive by forcing them all into the double tax.

Pass Through Response to CAP

As noted above, the Center for American Progress (CAP) released a paper this week calling for imposing a double tax on all US businesses with more than $10 million in revenues. The paper has innumerable flaws, but it essentially makes three basic points worth reviewing:

- Pass through businesses contribute to income inequality;

- Pass through businesses are “lightly” taxed and cost the government $100 billion a year in lost revenues; and

- All US businesses above $10 million in revenues should pay the double corporate tax.

You’ll notice that points one and two are merely a rehash of last year’s study by a number of Treasury and NBER economists (Treasury) on effective tax rates for businesses. That study too was deeply flawed. You can read our initial critiques here and here, and we build on those concerns below.

Point three, on the other hand, is totally new territory. CAP would extend the harmful double tax currently imposed on C corporations and apply it to all businesses over $10 million in revenues.

CAP makes no attempt to defend this position on economic grounds, and for good reason. The corporate double tax is widely understood to reduce domestic business investment, lower wages and job creation, and generally encourage the migration of businesses from the US to other countries. Here’s our 2011 EY study on the topic:

The double tax is economically important and can distort a number of business decisions. One important such distortion arises because the double tax mainly affects business income generated by activities financed through equity capital within the C corporation form. Interest expenses are generally deductible by businesses, leading to a tax bias in favor of financing with debt rather than equity. The double tax thus raises the cost of equity financed investment by C corporations relative to debt financed investment and provides an incentive for leverage and borrowing rather than for equity-financed investment. Accordingly, the double tax contributes to the tax bias for higher leverage. Greater leverage can make corporations more susceptible to financial distress during times of economic weakness.

The double tax also increases the cost of investment in the corporate sector relative to the rest of the economy. This tax bias against investment in the corporate sector leads to a misallocation of capital throughout the economy whereby capital is not allocated to its best and highest use based on economic considerations. This reduces the productive capacity of the capital stock and dampens economic growth. As noted before, the diversity of organizational forms can be seen as a useful choice for businesses to make in organizing themselves, but the impact of differential treatment should be recognized. Finally, the double tax raises the overall cost of capital in the economy, which reduces capital formation and, ultimately, living standards.

Reformers might disagree on what the top business tax rate should be, but very few tax experts openly advocate for expanding the double tax. So in this instance, CAP is making itself an outlier in the tax discussion and an advocate for fewer jobs and less investment here in the United States. Not the place to be.

Treasury “Findings” Exaggerated

CAP writes that the Treasury study “implies that the growth of these lightly taxed pass-through businesses cost the federal government $100 billion in 2011.” Notice the use of the weasel word “implies”? CAP had to insert that word because the Treasury study explicitly does NOT find that the growth of the pass through sector has cost the government revenue.

This nuance was lost on the tax reporters at BNA, who dutifully reported that “The growth of passthroughs cost the U.S. $100 billion in lost tax revenue in 2011, according to a Center for American Progress report released Aug. 10.” But Treasury never says that! Here’s what the Treasury study says:

We find that allocating partnership income to traditional businesses results in an average tax rate on business income of 28.1%, which exceeds the average tax rate on business income of 24.3% in 2011 by 3.8 percentage points. Since the pass-through sector earned $1.1 trillion in business income in 2011, an additional 3.8 percentage points on the tax rate would have generated 97 billion more dollars in business tax revenue, which would amount to an approximately 15.5% increase in tax revenues from business income on an annual basis.

We stress that this exercise is not a projection for the likely effects on tax revenue from business tax reform. It is mechanical and assumes no behavioral responses, but has the advantage of being transparent. (Emphasis added)

Transparent? Hardly. BNA wasn’t the only news outlet to get the story wrong. It is wholly misleading for Treasury to toss out this estimate and then say in effect, “Oh, just kidding.”

Treasury has to say “just kidding” because the whole exercise of taking 2011 pass through income and taxing it according to 1980 rules is ridiculous. Which tax rates apply to the newly designated corporate income, those in force today or those from 1980? What about the growth in the business tax base? As we’ve noted in the past, business income today makes up 11 percent of our national income, while it was only 9 percent back in 1986 – that’s bigger and it’s the result of the shift in the taxation from the harmful double tax to the more efficient and competitive single layer pass through tax. Did Treasury adjust tax collections back to 1980 levels to account for this growth? No.

But are pass through businesses really taxed “lightly” as CAP so amusingly claims. No. There too, the Treasury estimates used by CAP have significant challenges. Here’s a list of their problems:

- Treasury uses 2011 filings and tax rules, so it misses the sharp rate hike on pass through businesses that took effect in 2013. The fiscal cliff resolution hiked top tax rates on pass throughs from 36 to 39.6 percent, imposed the new 3.8 percent surtax on top of that, and then restored the old Pease limitation on deductions. The net effect of all this was to increase the tax top tax rate on pass through businesses from 35 to 44.6 percent! Treasury issued their paper just last year, so they could have adjusted their estimates to reflect these higher rates, but they chose not to.

- Treasury assumes shareholder-level taxes add another 9 percentage points to the C corporation average rate, but that assumption is based on economic literature from 2004 rather than tax collections from 2011. It also employs some heroic assumptions about the composition of corporate distributions (Footnote 16 in the Treasury report). A subsequent CRS study earlier this year found that shareholder level taxes added just 2.3 percentage points to the effective tax rate of C corporations, while a recent report by the Tax Policy Center found that only 24 percent of C corporation shares are held in taxable accounts, or less than half the level as assumed by Treasury. More work needs to be done on this!

- For partnerships, Treasury fails to differentiate between active business income and investment income previously taxed at the corporate level, which is obviously taxed at lower rates. The study notes that 70 percent of partnerships are “finance and holding companies” and that “capital gains and dividend income, which are taxed at preferred rates, amount to 45% of partnership income.” To the extent these partnerships are investing in C corporations whose income is already taxed at the entity level, it makes sense that their effective tax rate would be lower than the top statutory rate. Perhaps this partnership income should be included in the C corporation bucket, since they are C corporation shareholders? Something needs to be done to fix this, otherwise you have C corporations credited with both layers of tax, but their partnership shareholders credited with the second layer of tax only.

- Treasury attributes about twenty percent of partnership income to “Unidentified TIN type” and “Unidentified EIN.” It then appears to assume this unidentified income was taxed at a blend of the two lowest applicable rates, resulting in an even lower average rate for partnerships.

- Treasury appears to use “taxable income” in the denominator when calculating their effective tax rates, at least for C corporations. You can read our full concern with this here, but the net effect of using taxable income as the base is to overstate the effective tax rate for C corporations versus other business types.

- Treasury fails to account for the size of business. This is material because while C corporation income comes almost entirely from large, multinational companies, a large portion of pass through income is earned by smaller, less profitable companies who pay the lower income tax rates. To get a true comparison of tax burdens, Treasury should have broken down their estimates by size.

So Treasury overstates the tax paid by C corporations and understates the tax paid by pass through businesses, and then concludes that C corporations pay more. Somebody in the economic world needs to take another run at this topic.

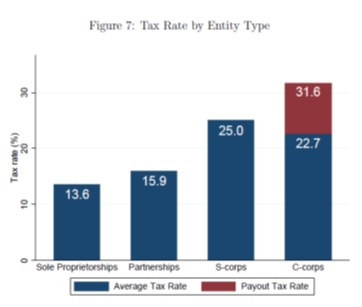

Here’s is the effective rate table from the Treasury report that is reprinted in the CAP report.

You’ll notice that even with Treasury’s flawed approach, S corporations pay a higher effective tax rate than C corporations on their income when it is initially earned, even with the lower rates on pass through businesses in place back in 2011. This is a reality that many policymakers do not understand. S corporations and other pass through businesses pay tax on their income when it is earned, just like C corporations. And today, their top tax rate is much higher than the C corporation rate. Our effective rate study from 2013 included the higher, post-fiscal cliff rates and it found S corporations pay the highest effective rates of all.

So it’s simply inaccurate for CAP to argue that the government would collect more in taxes if it forced businesses paying a top marginal tax rates of 44.6 percent to instead pay the lower C corporation rate of only 35 percent.

What about income inequality? Here’s what CAP says:

Until recently most analyses of income inequality, such as that by Thomas Piketty in Capital in the 21st Century, have ignored the role of pass-through income in the U.S. tax system by allocating it according to a standard economic formula. But, as this report will highlight, it is impossible to understand the growth of income inequality without a deeper look at pass-through income: about 40 percent of the increased share of income going to the top 1 percent of households is explained by pass-through income—twice the contribution of other forms of capital, such as corporate stocks and bonds.

And here’s what we wrote about the Treasury report last year. It all applies here:

Pass through taxation doesn’t add to “income inequality.” C corporation tax treatment masks it. This is something we have written about in the past.

For example, Warren Buffett owns a large share of Berkshire Hathaway. That corporation pays no dividends and Buffett never sells any stock, so if one was just looking at the tax rolls, Buffett’s reported income is relatively low despite the fact that he’s one of the richest men on the planet. All his income is effectively hidden within Berkshire’s corporate structure. Treasury touches on this dynamic in a footnote at the bottom of page 2:

‘Note that this evidence may seem to suggest at first glance that at least a portion (e.g., perhaps 56% x 35% = 20%) of the rise in the top-1% income share could reflect merely a change in how business income is reported on Form 1040 returns: before annual business income taxes (as pass-through income subject to ordinary individual income taxes) rather than after annual business income taxes (as post-corporate-income-tax dividends or capital gains distributions).’

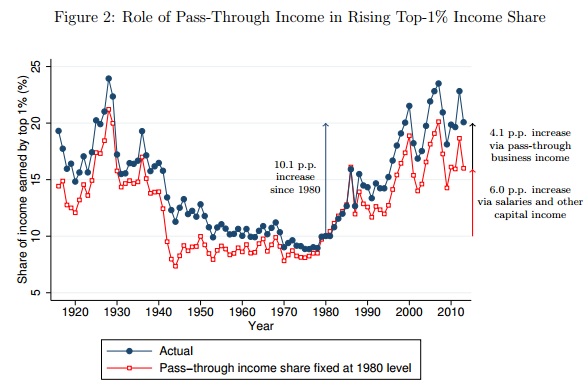

Figure 2 at the back of the paper helps Illustrate this dynamic.

The blue line shows the rise of income inequality, thanks to data from Piketty and Saez. The red line shows how much less inequality would have risen if businesses back in 1980 were taxed as businesses in 2013 – i.e. all that income showed up on the individual tax forms rather than the corporate ones. Lesson: C corporation taxation masks income inequality.

So the economists at Treasury and the NBER issue a flawed study on effective tax rates, CAP repeats the core message and uses it to drive a policy of double taxing US businesses, and the tax press repeats it all without comment or analysis. The assault on private enterprise continues.

BNA Tax Plan Comparison

BNA has a nice chart showing the tax proposals of Clinton and Trump. It is copied below. There is one correction we’d make, however. For Clinton, all those tax hikes she has planned for individuals, capital gains, and estates would also apply to pass through businesses.

So for an S corporation that right now pays 39.6 percent, plus the 3.8 percent ACA surtax, plus the reinstated Pease limitation on deductions, Clinton would add:

- The Buffett minimum tax of 30 percent;

- A 4-percent surtax on income above $5 million;

- A higher, 42.4 percent tax on capital gains held less than two years; and

- Higher estate tax rates and a lower exemption levels.

Clinton would raise taxes on pass through businesses when they earn income, when they are sold, and when their owners die. That strikes us as a pretty comprehensive assault on Main Street and far from “No Changes.”

COMPARISON OF PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATE TAX PLANS

| Trump | Clinton | House GOP | |

| Corporate Tax | Top rate of 15 percent, immediate expensing. | No changes to rate structures. Includes tax credits for businesses investing in community development, infrastructure and those that have employee profit-sharing. | 20 percent tax rate, immediate expensing. |

| Passthrough Taxes | Top rate of 15 percent, though Trump has hinted at possible changes to come. Immediate expensing. | No changes. | 25 percent tax rate, immediate expensing. |

| International Taxes | One-time tax of 10 percent on corporate cash held abroad when corporations repatriate the money. | Exit tax on unrepatriated earnings. | One-time tax on corporate assets held abroad, split at 8.75 percent on liquid holdings and 3.5 percent on illiquid holdings. Shift to territorial taxation of overseas income. Tax imported goods but not exports. |

| Individual Taxes | Three tax brackets of 12 percent, 25 percent and 33 percent, after initially proposing top individual rate of 25 percent. Eliminate carried interest deduction. | Buffett rule of 30 percent minimum tax on individuals with $1 million annual income. Also, 4 percent extra tax on individuals with annual income over $5 million. Carried interest taxed as ordinary income. | Three tax brackets of 12 percent, 25 percent and 33 percent. |

| AMT | Eliminate. | No changes. | Eliminate. |

| Estate Tax | Eliminate. | Lower threshold to $3.5 million for individuals, $7 million for married couples, with no inflation adjustor. Raise tax rate to 45 percent. Set lifetime gift tax exemption at $1 million. | Eliminate. |

| Capital Gains | Capital gains and dividends taxed at maximum rate of 20 percent. | Assets held less than two years taxed at ordinary rates. Reduce rate about 4 percentage points for each additional year asset is held until reaching a rate of 23.8 percent on assets held more than six years. | Deduction of 50 percent on net capital gains, dividends and interest income, producing rates of 6 percent, 12.5 percent and 16.5 percent on that investment income, depending on individual’s tax bracket. |