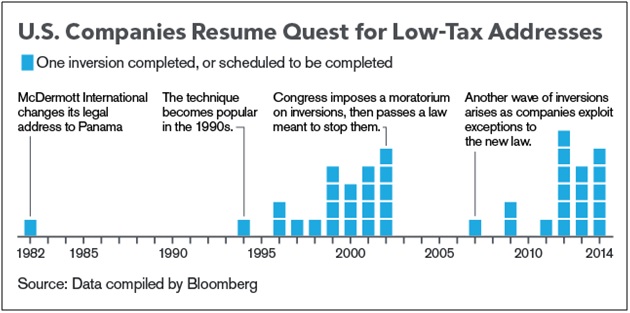

Yesterday’s letter from Treasury Secretary Jack Lew on inversions is just the latest headline on an issue that has dominated the tax discussion ever since Pfizer proposed to merge with AstraZeneca back in May. As the chart below notes, the number of companies moving their headquarters overseas is accelerating and it’s sending a strong signal that something is very wrong with our tax code.

The motivation for inverting is simple – it allows companies to avoid paying US taxes on foreign earnings. This is a uniquely American problem. Most major economies have territorial tax systems that only collect tax on income earned within the home country’s borders. The US, on the other hand, has a modified worldwide system that imposes US tax on all income regardless of where it is earned. The US system is “modified” in that it includes two significant exceptions to the worldwide approach:

- US taxpayers get a credit for any foreign taxes paid on their income; and

- US tax only applies to income that is repatriated (paid as a dividend) back the parent corporation.

As other countries have reformed their corporate tax codes and lowered their tax rates, the incentive for US companies to invert has grown.

Adding to their motivation is the policy risk that the US tax system will become even more punitive in coming years. High profile Democrats, including President Obama, have run on platforms that include “ending tax breaks that send jobs overseas” – i.e. ending or curbing a company’s ability to defer paying US tax on foreign earnings. No country, not even those few that still have worldwide tax systems, has ever adopted this approach. These proposals have never been seriously considered by Congress but they do expose the large gulf in vision on tax reform and serve as a potent reminder that action taken by Congress may not be business friendly.

So get out while you can.

The best way to address inversions is to reform the tax code to encourage more companies to organize here in the United States. The “fix it with comprehensive tax reform” response has been adopted by many tax writers in Congress, but how long can they stick with this refrain when nobody believes thoughtful tax reform is possible under this administration?

On the other hand, it is highly unlikely that Congress sits back and passively watches while all our best companies invert. Inversions may have limited real economic effects – most inversions are a legal exercise, not an economic one – but it looks bad and something must be done.

Secretary Lew argues for a two-step approach. First, enact legislation that raises the barrier to inverting in order to slow the tide of companies moving their incorporation papers overseas. Second, enact comprehensive tax reform that would make the US more attractive. It is hard to argue with step two here – and we’re glad to see the Administration support the concept of comprehensive reform – but step one is sure to prove ineffective. US companies are already structuring spin-offs that would get around the proposed, tougher anti-inversion rules.

We have a better idea that also involves two steps.

Why not officially adopt a territorial system now, and then move comprehensive tax reform later? After all, what’s the difference between Congress enacting a territorial system through a statute and companies acting organically to accomplish the same end through deferral and inversions? You end up in the same place. Moreover, how much could a shift to a statutory territorial system cost the US Treasury if we already have a de facto territorial system in practice? It can’t be much, so just make it official and remove the incentive for US companies to jump through all these legal hoops in order to invert.

Then the discussion could shift to the real issues confronting the tax code, including the excessive tax rates we impose on individuals, pass-through businesses, and US corporations alike. The corporate community is right to argue that high US taxes are driving investment and jobs overseas. These excessive rates are not limited to corporations – they include even higher rates on individuals and pass-through businesses – and, unlike inversions, excessive tax rates have a tangible and negative effect on our economy. That’s the real challenge with our current tax code and that’s what real tax reform needs to address.