Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) released his long-awaited tax plan yesterday. The Chairman has worked hard to put out a plan that addresses the biggest challenges faced by the tax code, and he should be applauded for keeping this effort alive.

From day one, Camp has been our lead in promoting comprehensive reform that addresses both the individual and the corporate tax codes. Such an approach was needed if pass-through businesses like S corporations and LLCs were going to be treated in an even handed manner. This priority of leveling the playing field was embraced by our Main Street letter, signed by more than 70 business associations representing millions of employers, that called for equalizing the top rates on active income paid by all tax payers—individuals, pass through businesses, and corporations alike.

Somehow, however, that fairness message got lost in the drafting of the draft. So did simplicity.

Consider the new rate structure. The Committee says they reduced the rates from seven to just two – 10 and 25 percent. But they also included a 10 percent (10 percentage points, that is) surtax on incomes above $450,000. A surtax is really just another bracket by a different name. Everybody knows that. In fact, that’s how we got the current 39.6 percent bracket. It started as a Clinton-era 10 percent “surtax” on the old top rate of 36 percent, and just evolved into what it really is – a new, higher tax bracket.

So really there are three tax brackets – 10, 25, and 35 percent.

Then there is all that other stuff. The Obamacare 3.8 percent investment surtax is still there. For some reason, tax reform couldn’t address that atrocity. A new tax applied to a new definition of income, it taxes most forms of investment income above $250,000, including the S corporation income of passive shareholders.

There’s also a new, broader application of payroll taxes to S corporation income, including income from capital intensive businesses like manufacturers. Years ago, Congressman Charlie Rangel (D-NY) proposed to apply payroll taxes to income earned by S corporations in the personal services industries. Senator Max Baucus (D-MT) proposed a similar plan several years later. The rationale was to crack down on tax cheats, but the proposals went much further than that and would have raised taxes on businesses that were fully complying with both the spirit and the letter of the law. The Camp proposal would take the Rangel-Baucus idea even further by applying payroll taxes (in this case, SECA) to 70 percent of S corporation income earned by all active S corporation shareholders, regardless of what industry they are in. That appears to add 11.6 percentage points to the tax rate of S corporations below the FICA cap and another 2.7 points to income above that.

Then there’s the disparate application of the new 35 percent bracket depending on which industry your business is in. President Obama proposed several years ago to cut corporate tax rates to 28 percent for all C corporations, but if you were in manufacturing, you got a special lower rate of 25 percent. The Camp draft takes this “winners and losers” approach a step further, offering pass-through businesses with production income a 25 percent top rate while other forms of income (retail, engineering, services, etc.) pay a top rate ten percentage points higher.

Finally, there are the recaptures and cliffs. A cornerstone of “reform” has always been to eliminate thresholds and phase-outs as much as possible. A key part of the Bush tax reforms in 2001 and 2003 was to eliminate the notorious phase-outs known as PEP and Pease. Nothing makes the code more complicated than loading it up with one income phase-out after another. Low-income families today face a potent combination of phase-outs from the EITC, the child tax credit, and the new health care reform subsidies. The marginal rate cliff resulting from these phase-outs is the reason the CBO estimated the health care reform subsidies would encourage 2 million workers to stay home. The Camp draft invents several new ones that will impact pass-through business income. There’s the recapture of the 10 percent bracket, standard deduction, and child credit. That starts at $300,000. Then there’s the application of the new 10 percent surtax to previously untaxed employer-provided health benefits. That starts at $450,000.

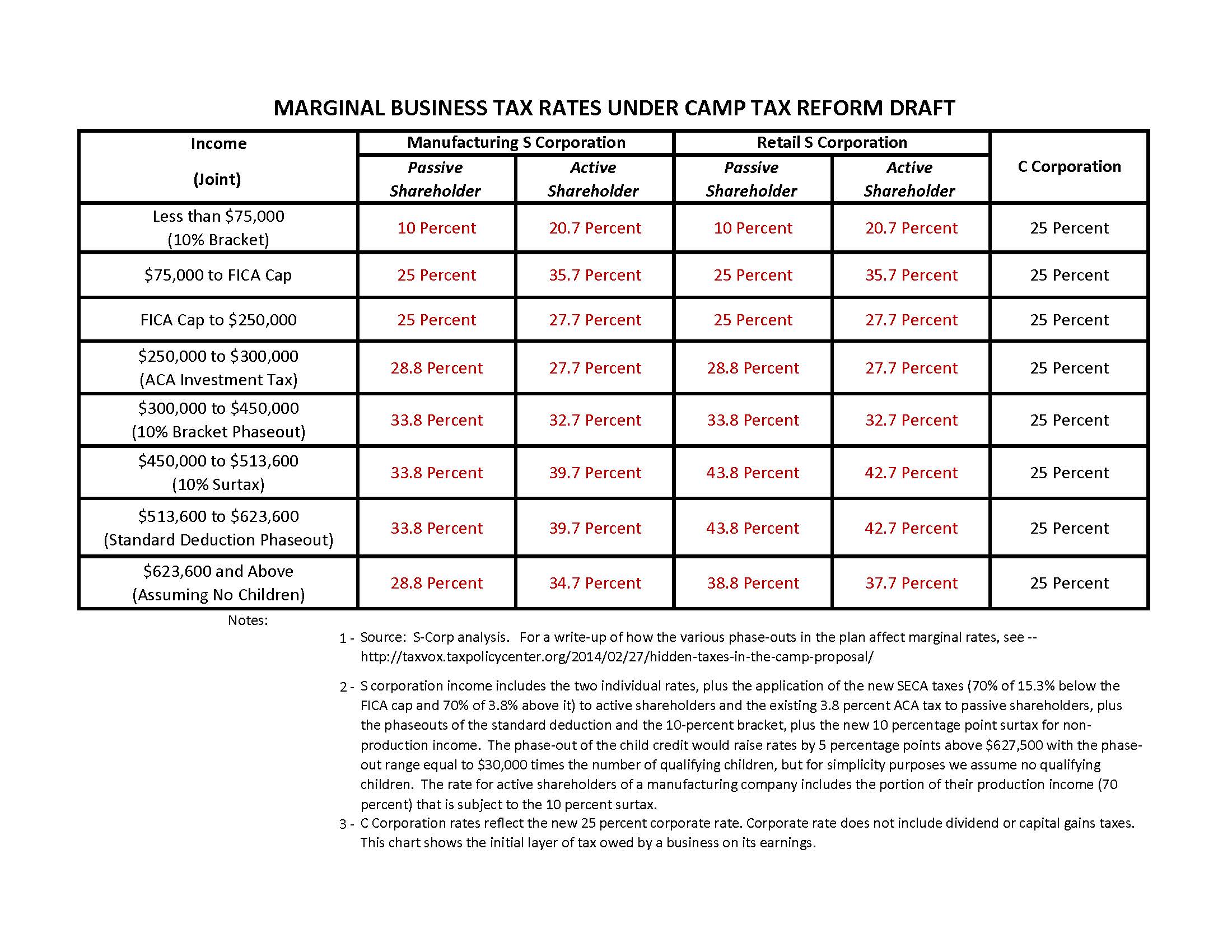

The net result is a bewildering array of rates and thresholds for pass-through businesses, with at least 11— not two—different marginal rates. This chart is based on our first look at a very complex plan, so it might have some of the details wrong, but gives you a general idea of what we’re up against.

See the rate schedule on the right side for C corporations? That’s what tax reform looks like. Rational and even-handed. The rate schedule for individuals looks pretty good too, especially if you ignore the effect on marginal rates of payroll taxes and low-income credits, as this table does (we simply didn’t have the time to figure it all out).

The rate schedule for S corporations, on the other hand, is a mess. Why should it matter what industry you are in, or how involved you are in the business? Business income should be business income.

This is not to say that there aren’t good items in the plan. There are lots of them, including the lower marginal rates on labor and business income, the repeal of the individual AMT, the repeal of a zillion miscellaneous special-interest tax credits, the handful of provisions to improve S corporation governance, and more.

But each of these victories for fairness and simplicity is offset by a provision that moves in the opposite direction, like raising the tax burden on capital expenditures, increasing taxes on retirement savings, and increasing the top tax rate on capital gains and dividends.

The net effect of all this is that, even with the sharp reduction in corporate tax rates, the Camp draft increases the cost of investing in the United States! That’s not our assessment. That’s the assessment of the economic analysis circulated by the Committee to promote the plan.

So how did we get to this result? The main culprit has got to be the remarkable number of constraints the Committee placed on its efforts before they began crafting the plan, including:

- Budget neutrality;

- Neutrality with respect to income classes;

- Establishing a top rate of 25 percent for individuals, corporations and pass through businesses;

- No cross-subsidization between individuals, pass-through businesses and corporations; and

- Excluding health care from the plan, including health care taxes.

Einstein couldn’t have drafted a reasonable reform plan under these constraints; neither could the capable staff at the Ways and Means Committee. The result is that they neither stayed within their constraints – 3, 4, and 5 were all sacrificed to one degree or another – nor did they achieve the level playing field or simplicity at the heart of any real tax reform.

This is a discussion draft, so we’ll be working with the Committee to identify our concerns and work on changes. Our message to the Committee will be focused on what’s in this post. We will encourage them to return to first principles and remember why they started down the path of tax reform in the first place. The outlook for reform moving through the Congress may be bleak, particularly the Senate, but the ideas put forward by plans like this live on forever. It’s important to get them right.