Last week, the IRS released a 150-page document outlining how it will spend some $80 billion in new funding authorized in the Inflation Reduction Act. The good news is that the report places a heavy emphasis on improving customer service. That includes processing returns faster, increasing the number of forms that can be filed electronically, improving its telephone service, and other important steps. It also includes a host of new initiatives and milestones designed to ensure those objectives are met.

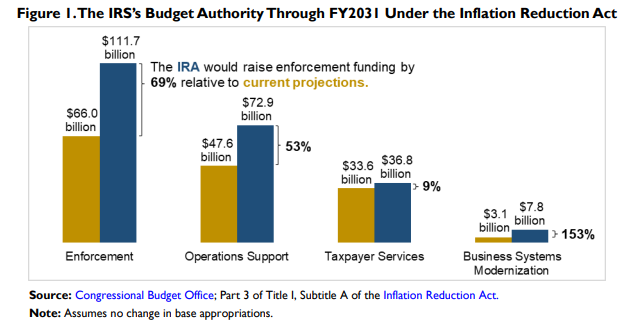

Beyond that, however, the plan is positively obtuse when it comes to “enforcement activities” or how the agency will leverage the new funding to bring in additional tax revenue. The basic premise behind the funding boost was that more enforcement dollars would allow the IRS to more effectively chase down tax cheats, yielding $180 billion in new revenue according to Congressional scorekeepers.

How many more auditors will the IRS hire? The report doesn’t say, which is odd given it is the most contentious aspect of the funding increase. As others have pointed out, a document released by Treasury last year projected that the new funds would enable the IRS to hire an additional 87,000 employees by 2031, with most of those new hires working on enforcement.

Treasury pushed back, arguing that many of these new employees would simply replace retiring ones, and claiming that the actual increase in workers would be just 25 or 30 percent. That estimate, however, is inconsistent with the Congressional Budget Office’s analysis, which forecasts a doubling of the workforce:

Spending would increase in each year between 2021 and 2031, though the highest growth would occur in the first few years. By 2031, CBO projects, the proposal would make the IRS’s budget more than 90 percent larger than it is in CBO’s July 2021 baseline projections and would more than double the IRS’s staffing. Of the $80 billion, CBO estimates, about $60 billion would be for enforcement and related operations support. [emphasis added]

The CBO also made clear that most of the funding increase – and presumably new hires – is in enforcement, not customer service.

IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel justified leaving out overall employment numbers by promising the release of additional estimates in the future. According to Bloomberg Tax:

Werfel said the agency plans to soon release employment estimates for fiscal 2025 but said a lot is involved in projecting staffing levels, particularly as the agency implements new technologies.

“I hope that we can get better and better at forecasting, but I just think it’s good management and leadership practice to look at these things in a three-year window and provide that type of precision,” Werfel said.

So the new plan fails to estimate headcounts, but it does emphasize that audit rates on taxpayers earning less than $400,000 will not increase. But in parsing the language, we find here the report is just a little obtuse too. The word “historical” is doing some heavy lifting:

Pursuant to Treasury’s directive, small businesses and households earning $400,000 or less will not see audit rates increase relative to historical levels. We will increase our focus on segments of taxpayers with complex issues and complex returns where audit rates are minimal today, such as those related to large partnerships, large corporations, and high-income and high-wealth individuals.

Under the Inflation Reduction Act, the IRS needs to raise an additional $180 billion from somebody. Increased audits of high-wealth individuals and large corporations may provide some of that additional funding, but those taxpayers are already highly scrutinized and unlikely to provide all of it.

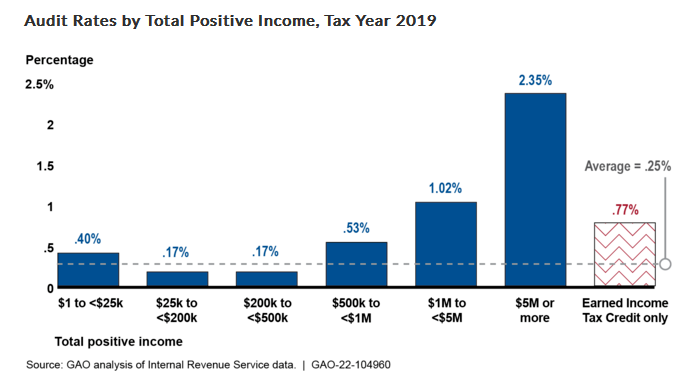

As this data from the GAO attests, the IRS already focuses its enforcement efforts on higher income taxpayers. Moreover, these rates are annual, so they understate the odds of being audited over a period of years. If a taxpayer makes more than $5 million a year from four separate taxable entities, their chance of getting audited over a decade is not 2.35 percent but rather many times that percent.

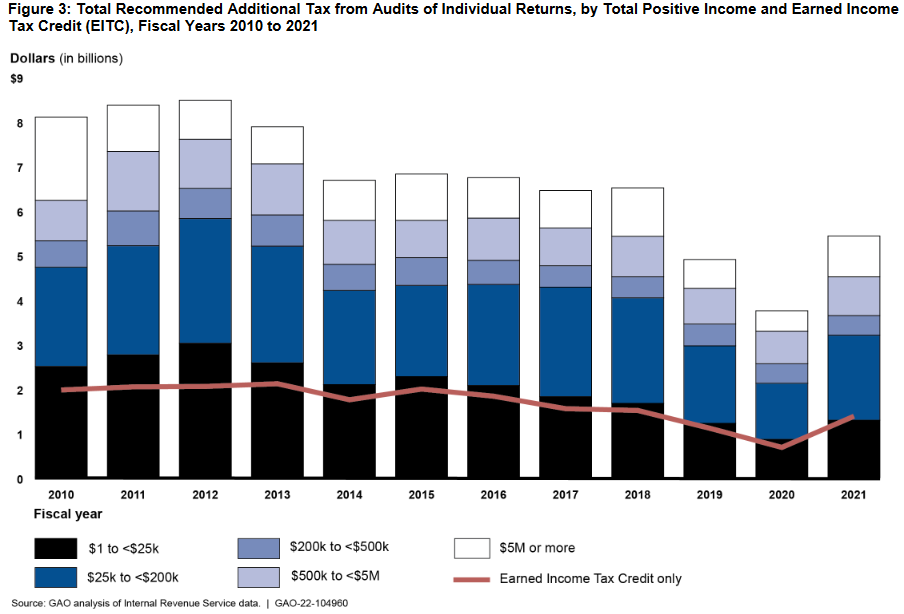

The GAO also found that the IRS’s record of collecting additional tax stems mostly from lower income taxpayers. From 2010 through 2021, most of the additional tax recommended by the IRS was from taxpayers making less than $200,000. For the Inflation Reduction Act to be successful, some of the $180 billion will have to come from those taxpayers. How do you raise revenue from taxpayers making under the $400,000 threshold while keeping to the promise outlined above? Here’s CBO again:

The proposed increase in spending on the IRS’s enforcement activities would result in higher audit rates than those underlying CBO’s baseline budget projections. Between 2010 and 2018, the audit rate for higher-income taxpayers fell, while the audit rate for lower-income taxpayers remained fairly stable. In CBO’s baseline projections, the overall audit rate declines, resulting in lower audit rates for both higher-income and lower-income taxpayers. The proposal, by contrast, would return audit rates to the levels of about 10 years ago; the rate would rise for all taxpayers, but higher-income taxpayers would face the largest increase.

So apparently “current” audit rates are less than “historical” audit rates, which means they will be going up. The CBO’s analysis also allows for enforcement activities other than audits:

Activities other than audits—such as collections and automated screening and document matching—are not constrained by the Secretary’s directive, and under the 2022 reconciliation act, the amounts they generate will be greater for taxpayers with all amounts of income, CBO projects.

All of this assumes the IRS will stick to the Secretary’s directive. Will it? The directive reflects a political promise made by the President and his Treasury Secretary. When they are gone, we expect the directive will go too. This is a ten-year plan, after all.

Where does that leave us? For taxpayers, including S corporation owners, making more or less than $400,000 a year, the chances of getting audited are going up. Way up. Funding for IRS enforcement increased by 69 percent under the Inflation Reduction Act. That new funding will allow the IRS to hire thousands of new agents/auditors/enforcement personnel (choose your descriptor, it doesn’t matter) and those employees are going to be on the hook to increase collections by $180 billion over the next ten years.

None of that is made clear in the IRS report released last week, but it’s still the plan.