Submit your email below to subscribe to the Washington Wire:

Shrinking Main Street

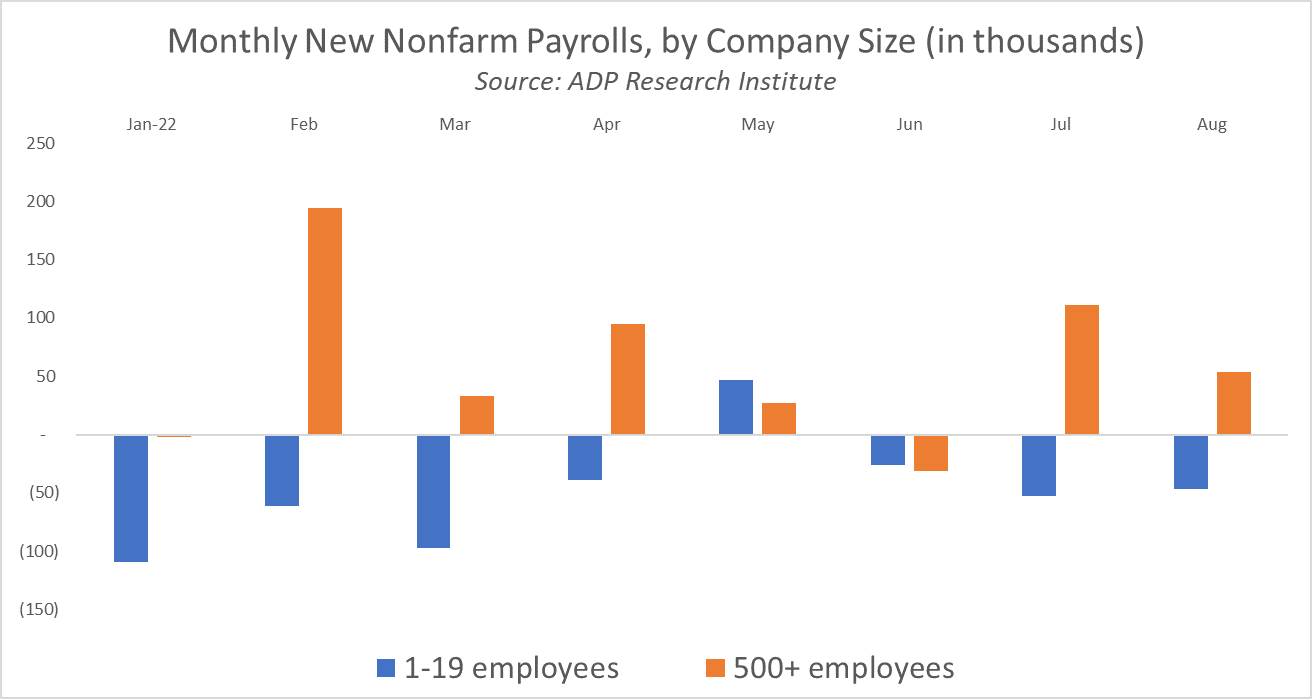

ADP is out with its revised, independent jobs forecast this week and it shows continued challenges for Main Street. As with past reports (before they revamped the product to produce a truly independent alternative to the monthly BLS reports), the latest data shows a continued divergence in the economy, with larger businesses adding jobs while smaller firms shed them.

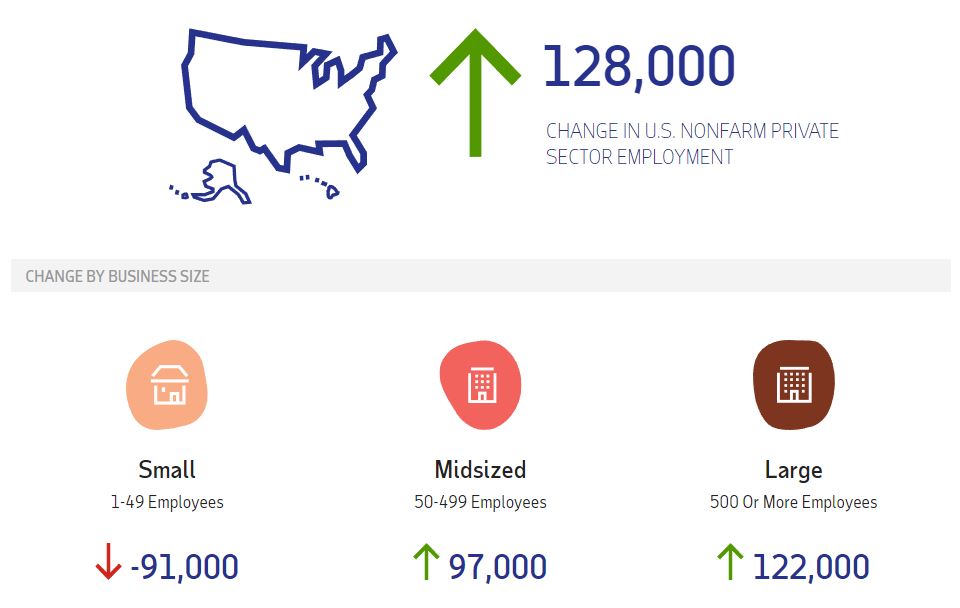

According to ADP, private employers created 132,000 net jobs in August. But while large firms (those with more than 500 employees) added 54,000 jobs, small businesses with less than 20 employees contracted by roughly the same amount, losing 47,000 jobs. As the chart below shows, this is part of an ongoing trend:

Add the numbers up and you find that, since the start of 2022, small businesses have lost a whopping 385,000 jobs while employment at larger firms increased by 481,000.

Why is the small business sector contracting? Inflation is definitely a culprit. As CNBC recently reported, small businesses are facing an unprecedented rent crisis:

Inflation has been the No. 1 concern of small businesses for some time, as high prices in raw materials, labor, energy and transportation cut into margins. Higher rents, and landlords feeling more aggressive the farther away the nation moves from the peak of Covid, have compounded the hit from inflation being felt on Main Street.

How much has rent spiked? Forty-five percent of small businesses surveyed said they’re paying at least 50 percent more in rent than they did prior to Covid, while 12 percent said rent payments have tripled. At the same time, 77 percent of respondents reported revenue that’s still below pre-Covid levels, a dynamic that could worsen as the Federal Reserve takes steps to shut down inflation.

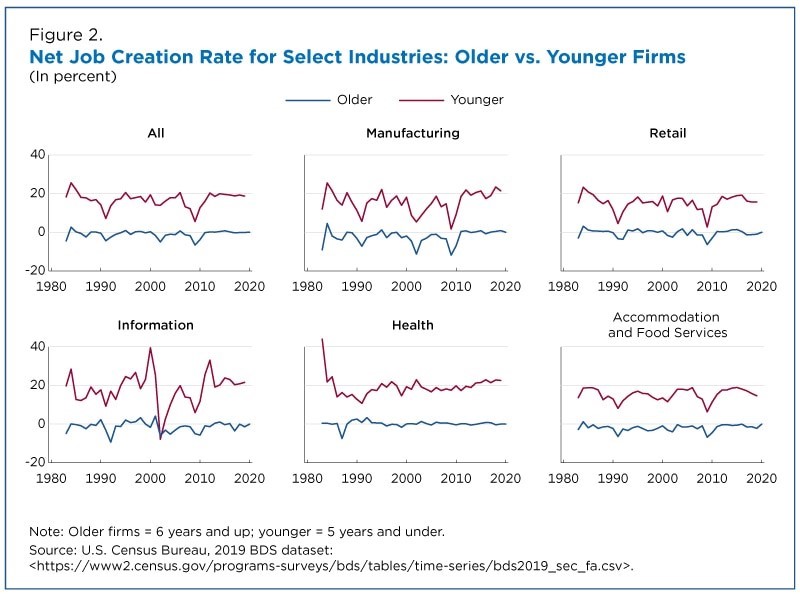

But if aggregate employment numbers are on the rise, why does it matter that Main Street is shrinking? As we’ve written before, small businesses have historically been the drivers of job creation and economic expansion, accounting for nearly two-thirds of new jobs historically. Which makes sense – compared to larger, established companies, smaller, younger firms are more likely to hire and expand. Data from the Census Bureau bears this out:

The bottom line is that this migration of workers from small businesses to large, publicly-traded firms is bad news for most of the country. As our employment heatmap from EY shows, most of the country relies on non-public firms for their job base:

At the end of the day, only so much economic consolidation can occur before growth and hiring levels inevitably flatline. We need smaller businesses and startups for net job creation – unfortunately, the post-pandemic economic environment isn’t helping. Nor is the adoption of policies that raise their costs and increase the burden of government. Something to keep in mind the next time the White House touts an otherwise positive job report.

Inflation Reduction Act Targets All Taxpayers

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has kicked off a rigorous debate over the $80 billion in new funding for the IRS. Republicans argue the funds will be used to audit the middle-class while the Biden Administration assures us that nobody under $400,000 will see increased audit “rates.”

So where does the truth lie? In short, the IRA will substantially increase the number of IRS audits over the next decade, including higher numbers of audits for middle-income taxpayers and Main Street businesses. Here’s the breakdown.

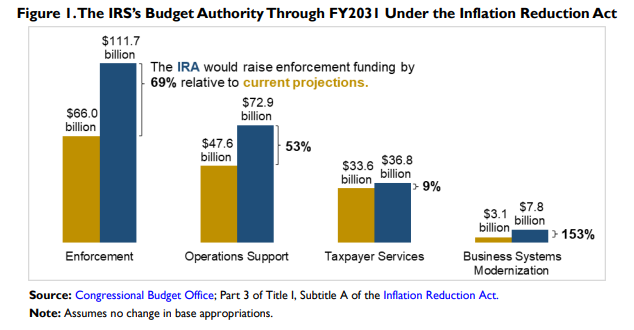

The IRA allocates some $80 billion over the next decade in additional funding to the tax-collecting agency, with more than half of that going towards what the bill describes as “improving taxpayer compliance.” The Congressional Research Service has a handy chart that shows how the money is divvied up:

Those new “enforcement” dollars are supposed to reduce the so-called tax gap, or the annual difference between what Americans should pay versus what the IRS brings in. The premise is that there’s a treasure trove of uncollected money out there, but the IRS lacks the resources to chase it all down.

This notion is pure fiction, as we’ve discussed in the past. Let’s say the annual tax gap is around $600 billion annually (the estimate keeps changing, it’s based on old data, and the whole thing is highly questionable, so we’ll stick with a round number) while congressional scorekeepers estimate the $45.7 billion in new IRA enforcement funding will raise an additional $204 billion in gross revenue.

That’s just 3 percent of the tax gap over the next decade. By that math, Congress would need to give the IRS an additional $1.5 trillion and hire hundreds of thousands of additional employees to close the entire gap. That’s obviously ridiculous, so perhaps the tax gap is not the treasure trove tax collectors think it is?

Worse, the new funding will result in a massive increase in IRS enforcement activity. As many Republicans have pointed out, a document released by Treasury last year projects the new funds would enable the IRS to hire an additional 87,000 employees by 2031.

The IRS currently employs about 80,000 workers, so the IRA would effectively double its workforce, yes? That’s what the CBO thinks:

Spending would increase in each year between 2021 and 2031, though the highest growth would occur in the first few years. By 2031, CBO projects, the proposal would make the IRS’s budget more than 90 percent larger than it is in CBO’s July 2021 baseline projections and would more than double the IRS’s staffing. Of the $80 billion, CBO estimates, about $60 billion would be for enforcement and related operations support. [Emphasis added]

But Treasury is pushing back, arguing that some of these new employees would replace retiring workers. They claim the actual increase in workers will be just 25 or 30 percent. That estimate, however, is inconsistent with Treasury’s own estimates back when they first proposed the $80 billion funding hike:

Because the expansion in the IRS’s budget is phased in over a 10-year horizon, each year the IRS’s workforce should grow by no more than a manageable 15%. By the end of the decade, however, the IRS’s budget would be roughly 40% above 2011 levels in real terms as a result of this proposal.

In 2011, the IRS had nearly 100,000 workers, so a forty-percent increase would translate to 140,000 workers. Not the doubling estimated by the CBO, but way more than Treasury is telling people now. Treasury needs to get its story straight.

Obfuscation aside, what is clear is that thousands of new IRS employees will be engaged in enforcement activities that result in higher numbers of audits – that’s where the additional $204 billion comes from, after all. Here’s the New York Times inadvertently highlighting our concerns:

The I.R.S. is beefing up its staff to keep pace with the growth in taxpayers and to replace departing employees. The Biden administration expects that about 50,000 I.R.S. employees will retire within the next decade and that the agency will hire 87,000 new employees, bringing the overall size of the agency to around 120,000. The number of enforcement agents is expected to double to about 13,000 from 6,500 over the next decade.

So you’re significantly increasing the overall size of the agency over a short time period and doubling the number of enforcement agents, even as you replace many of the existing auditors with younger, less experienced auditors? No, nothing to worry about here. Bottom line is it’s simply incorrect to argue there will not be a substantial increase both in the number of auditors or audits under the new law.

What about the argument that only taxpayers and businesses over certain income thresholds will see increased activity? We’re seeing lots of obfuscation there too, and it stems from a letter Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently wrote to senators:

These resources are absolutely not about increasing audit scrutiny on small businesses or middle-income Americans. As we’ve been planning, our investment of these enforcement resources is designed around the Department of the Treasury’s directive that audit rates will not rise relative to recent years for households making under $400,000.

And here’s the directive letter to IRS Commission Chuck Rettig:

Specifically, I direct that any additional resources—including any new personnel or auditors that are hired—shall not be used to increase the share of small business or households below the $400,000 threshold that are audited relative to historical levels. This means that, contrary to the misinformation from opponents of this legislation, small business or households earning $400,000 per year or less will not see an increase in the chances that they are audited.

First, this directive is pure political theater. Just as no Congress can tie the hands of a future Congress, no Treasury Secretary can tell the IRS what to do once she’s left office. Yellen likely won’t be in a position to enforce these demands in a year or two, let alone in 2031.

But what about while she’s in office? Notice her use of weaselly phrases like “audit scrutiny” and “audit rates” and audit “share” and increased “chances” and “existing resources” and “historic levels.” What exactly do those words mean? They mean the number of audits on households making less than $400,000 is going to increase, that’s what they mean. Here’s the CBO’s summary:

The proposed increase in spending on the IRS’s enforcement activities would result in higher audit rates than those underlying CBO’s baseline budget projections. Between 2010 and 2018, the audit rate for higher-income taxpayers fell, while the audit rate for lower-income taxpayers remained fairly stable. In CBO’s baseline projections, the overall audit rate declines, resulting in lower audit rates for both higher-income and lower-income taxpayers. The proposal, by contrast, would return audit rates to the levels of about 10 years ago; the rate would rise for all taxpayers, but higher-income taxpayers would face the largest increase. [Emphasis added]

This assessment is consistent with a subsequent preliminary score of the Crapo amendment 5404, which revealed that 10 percent of the projected new revenues come from taxpayers making less than $400,000. How could that be without increased enforcement?

Biden economic advisor Jared Bernstein apparently didn’t digest the nuance of all this, assuring CNBC viewers that the new IRS funding does not “touch one taxpayer under $400,000.” That’s not correct. This after claiming earlier this month that most of the IRA’s savings were “front-loaded” and therefore would help reduce inflation. That’s not correct, either.

Last year we had Ryan Ellis on the Talking Taxes in a Truck podcast to talk about this issue. He outlined the pain and heartburn that Main Street business owners experience when going through an audit, describing the day the IRS audit letter comes as “that Pepto Bismol moment.” Even audits where no new tax is owed are costly and stressful. With the Inflation Reduction Act, futures on Pepto Bismol are going up, and they are going up for everybody.

Ditch the IRA

The Main Street business community today sent a letter to lawmakers with a simple message: many of the proposed tax policies in the Inflation Reduction Act would harm individually and family-owned businesses and should be rejected.

The letter was signed by more than 70 trade associations representing millions of Main Street businesses from every corner of the country and every sector of the economy, including NFIB, the National Restaurant Association, the Associated Builders and Contractors, the National Association of Homebuilders, and others. It makes clear that the Inflation Reduction Act, which the House is expected to take up this week, falls well short of its intended purpose:

Inflation is at 40-year highs, we have had two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth, and we are witnessing a shrinking small business sector, yet the Inflation Reduction Act does nothing to address these immediate issues even as it increases the burden of the tax code shouldered by America’s small and family-owned businesses.

The Biden Administration claims the savings in the IRA are “front-loaded” and will reduce the deficit in the short-term, helping to ease inflationary pressures. That is simply not the case. Recent analysis by the Congressional Budget Office, Penn-Wharton, and others shows the Inflation Reduction Act would increase prices in the short term and do little to bring them down in the long run.

At the same time, the bill would give the IRS an additional $80 billion in funding, more than half of which would pay for thousands of additional IRS agents to conduct millions of additional audits. We support addressing the tax gap and oppose illegal tax evasion, but as former National Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson observed recently, it is wrong and counterproductive to characterize the entire tax gap as willful tax evasion. From experience, we know many, if not most, of these additional audits will be conducted on the owners of family businesses who have fully complied with the tax code.

The letter also addresses the last-minute adoption of the Warner amendment, and how it chose to protect private equity investors at the expense of the small business sector.

Finally, the Warner Amendment adopted at the last minute presented the Senate with a clear choice between Wall Street and Main Street, and the Senate chose Wall Street. The amendment extends for two years the Section 461(l) cap on losses a business owner is permitted to claim. This $52 billion tax hike on pass-through businesses was adopted with almost no consideration, and the revenues it raises were used to offset the cost of exempting private equity investors from the fifteen-percent corporate minimum tax. The cap on active pass-through loss deductions is bad policy at any time, but it is particularly harmful when the economy is weak and an increasing number of businesses are suffering losses. The timing of this amendment’s adoption could not have been worse.

The Inflation Reduction Act fails to combat inflation while simultaneously raising the tax burden on small and family-owned businesses. The IRA is the last thing our country’s struggling Main Streets need right now; it’s time for lawmakers to abandon these policies and focus instead on the priorities of Main Street employers.

“Getting Less for More”

With inflation, we’re getting less for more. We have an armored car business, so fuel costs are more expensive. Our largest armored car contract is with the federal government and we forecast those rates out for five years at a time, so we weren’t expecting as significant of an increase this year. That’s one area where our costs are up but we aren’t making more money…We don’t have opportunities to bake these increased costs into our rates unless we’re getting new business, because many of our contracts are long contracts.

Unfortunately for the small business community, Johnson-Cope’s experience is hardly unique. A recent survey conducted by NIFB showed that confidence among business owners continues to deteriorate, resulting in sharp declines in new investment and hiring:

Later in the interview, Johnson-Cope commented on the ongoing labor crunch, stating: “We definitely compete with larger terms for talent, and it’s a challenge.” We’ve been sounding the alarm over this trend for months now, but it bears repeating. While larger firms continue to grow, the small business sector – historically the primary driver of economic expansion – is shedding jobs at an alarming pace:

It’s already challenging enough to come up with financial projections. In the current financial climate, it’s even harder to project what’s going to happen from my vantage point. Last week we were securing a construction project, and our client said we would have to reduce coverage because one reason they needed security was to monitor equipment. But because of supply-chain delays, they didn’t even have the equipment they needed.

Recent NFIB member surveys make clear that inflation is the number one concern for Main Street businesses right now. With the CPI and PPI indexes measuring forty-year highs, businesses are struggling to balance rising prices with the need to accommodate their customers. A recent analysis from Penn-Wharton, however, finds the Inflation Reduction Act would increase prices in the short term and do little to bring them down in the long term.

Early on in a new administration, a supplementary appropriation can increase enforcement resources allocated to examinations of noncompliant high-income taxpayers and the businesses they own.

About $264 billion of that underreporting tax gap is from individual income taxes, and nearly half of that amount—about $125 billion—comes from underreporting by pass-through business filers such as sole proprietors, farmers, and those earning rental, royalty, partnership, and S-corporation income. They are prime targets for stepped-up enforcement.

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) estimates that over the past 30 years, the tax gap has fluctuated in a narrow range—15 to 18 percent of total tax liability. Some view the tax gap as a possible major revenue source that could be used to close the federal budget deficit without raising taxes. In practice, though, the potential revenue gains from proposals to improve enforcement are quite limited. (Emphasis added.)

The IRS’s measure of the tax gap includes unpaid federal income, payroll, excise, and estate taxes. In its most recent study of noncompliance, the agency estimated the gross annual tax gap was $441 billion for tax years 2011-2013. Late payments and enforcement revenue reduced the gap by $60 billion each year.But the IRS estimate does not distinguish between taxpayer mistakes and intentional evasion. For example, it includes the honest errors made by taxpayers trying to comply with ever-changing and often-opaque laws. The IRS also includes the liabilities of well-intentioned taxpayers who acknowledge what they owe but are unable to pay.Moreover, the IRS may be overstating or understating the true tax gap. The agency uses a statistical method called “detection controlled estimation” (DCE) to account for noncompliance missed in audits of individual income tax returns. But that approach is being reconsidered or already has been rejected by other countries out of concern for its accuracy. Some researchers have found DCE effectively triples the estimate of the individual income tax underreporting gap…

Requiring third-party reporting of all income would likely raise compliance levels. However, this is not possible in all cases and even where it is possible it might require burden-some new reporting requirements for individuals and businesses. For example, individuals paying a contractor or purchasing a car might be required to file reports to the IRS reporting these transactions. Such broad expansions of reporting requirements would be excessively burdensome, and that this consideration outweighs the gains they might bring in increased compliance.Similarly, requiring much more detailed documentation, such as evidence supporting claims for deductions and credits or providing accounting records supporting business income claims, would quite possibly improve compliance. In some cases more detailed documentation may be appropriate. However, unless carefully targeted, this is likely to impose an unacceptable increase in cost on both taxpayers and the IRS and to decrease privacy.Another approach to improving compliance would be to change the tax code to remove tax benefits wherever there is the potential for abuse. For example, deductions for non-cash giving could be prohibited. This would prevent the overstatement of charitable deductions by some taxpayers. However, it would also impose a tax increase on the millions of taxpayers who currently take legitimate deductions for non-cash giving. Compliant taxpayers are likely to regard this approach as overly broad.

Equating the entire tax gap to “tax evasion” is just so disingenuous. And it’s also wrong; it’s incorrect. Evasion has a technical meaning under the law, and generally it requires mens rea, a criminal intent. So much of it is error, or inadvertent…there are a bunch of different types of noncompliance. And if you say [it’s all tax evasion] – and that’s what the Washington Post called it, that’s what the New York Times called it – then that creates distrust among the taxpayers of the tax agencies. [They’re asking], “why am I paying if you’re letting all these people off the hook?”Her last point is critical, because there’s no free lunch with the tax gap. Our Tax Code has one of the highest tax compliance rates in the world (84 percent) but maintaining that high collection rate depends on the annual good-faith submission of tax returns by millions of taxpayers. Cynically inflating the tax gap problem to increase the IRS budget will reduce confidence in the system. So will turning 87,000 new auditors loose on Main Street.

Recession, Inflation, and the Small Business Sector

Want to understand what’s happening in the economy? Look to inflation-adjusted data. Wage levels and company revenues are reported in nominal terms, while the GDP estimates are adjusted for inflation. That’s why they appear to be headed in different directions when, in fact, it’s all going south.

It’s also the reason inflation is something to be avoided, and something to be addressed quickly when it does appear. When you dump trillions of new dollars into the economy for a year or two, people and businesses feel wealthier and flush with cash. They spend more, increase commitments, and hire more workers.

So the initial phase of an inflationary cycle is characterized by increased demand by consumers, more investment by businesses, and increased employment.

But workers aren’t better off. In the last year, nominal wages rose 5 percent, so a typical worker’s annual income might have risen from $50,000 to $52,500. But inflation rose 8 percent, so those increased wages are actually worth less, just $48,500. The worker thinks she’s better off, but she’s actually losing ground. Here’s the BLS on the most recent data:

From June 2021 to June 2022, real average hourly earnings decreased 3.1 percent, seasonally adjusted. The change in real average hourly earnings combined with a 0.9-percent decrease in the average workweek resulted in a 3.9-percent decrease in real average weekly earnings over this period.

The effect on businesses is the same. All businesses, even the most sophisticated, measure their performance in nominal dollars. So early in an inflationary cycle, they make decisions under the illusion that their revenues are rising, and make investment and hiring decisions that the underlying realities don’t justify. Later in the cycle, they have to juggle the consumer’s changing purchasing decisions based on the same money illusion. The result is a massive amount of misallocated capital and labor.

That’s what’s happening to our nation’s retailers right now, who were slow to recognize an initial increase in demand for durable consumer goods and now are trying to catch up as consumers leave durable goods behind and focus on recession-proof goods instead. All that, as they try to manage rapidly changing prices at both the wholesale and retail level. Here’s the recent Walmart outlook that resulted in a massive sell-off of its stock:

Comp sales for Walmart U.S., excluding fuel, are expected to be about 6% for the second quarter. This is higher than previously expected with a heavier mix of food and consumables, which is negatively affecting gross margin rate. Food inflation is double digits and higher than at the end of Q1.

This is affecting customers’ ability to spend on general merchandise categories and requiring more markdowns to move through the inventory, particularly apparel.

During the quarter, the company made progress reducing inventory, managing prices to reflect certain supply chain costs and inflation, and reducing storage costs associated with a backlog of shipping containers. Customers are choosing Walmart to save money during this inflationary period, and this is reflected in the company’s continued market share gains in grocery.

Comp sales are up 6 percent, but inflation is up 8 percent. Like our worker, Walmart is worse off.

From the Main Street perspective, the debate over the definition of a recession is beside the point – as we’ve written in the past, the small business sector has been shedding jobs and paring back for months. Here’s the most recent ADP report showing how the economy has bisected between large and small firms:

Finally, the case that the legislative package unveiled earlier this week will reduce prices can only be justified if you focus on the deal’s broad parameters and ignore the details. In theory, reducing deficits would reduce price pressures, but only if the tax increases and spending reductions were focused on the demand side. The tax hikes in this package are shouldered by corporations, and one-third of those will be passed on to consumers in the form of price increases.

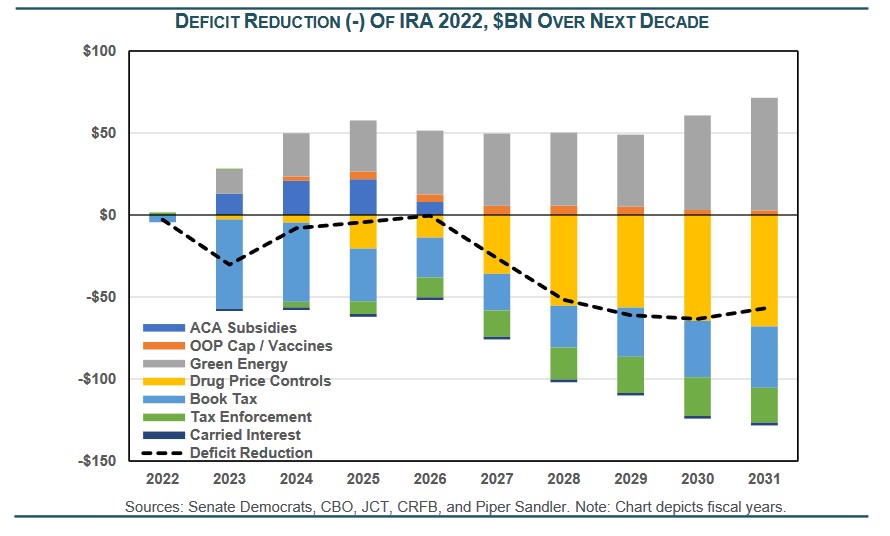

Moreover, the bulk of the deficit reduction doesn’t get going until 2027 and later. Until then, the bill is nearly budget neutral, suggesting it won’t have a significant impact on prices in the short term. This chart from Piper Sandler shows you the year-by-year effects. Just follow the dotted line.

So the economy is troubled by any measure once you account for rising prices, the small business sector is in recession already and has been for months, and the so-called Inflation Reduction Act is anything but. Still confused? Just adjust your perspective for inflation and you’ll uncover the truth.